Forum Crowding

Jurists and scholars have long debated (and often decried) the practice of forum shopping. Critics note, for example, that forum shopping both yields procedural gamesmanship and undermines the courts’ legitimacy, while supporters contend that competition for cases increases access to the courts and improves litigants’ experiences.

Such debates have overlooked the effects of forum shopping on an important constituency: litigants who have little choice over forum. When forum shopping causes a sudden influx of cases—when, that is, it crowds a forum—what happens to other cases that have nowhere else to go? Are busy judges—made busy by forum shopping—more prone to error?

In this Article, we conduct a novel analysis of the effects of such forum crowding. In particular, we draw on ongoing pathologies in patent litigation, which has been subject to extreme forum shopping for over a decade, to empirically examine the effects of these practices on other cases, including criminal and civil rights cases, which are subject to more stringent forum rules. We find that, in some crowded courts, these cases may get short shrift. And so we conclude by offering procedural reforms aimed at protecting these cases from being crowded out.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

In 1952, Judge Irving Kaufman issued the first district court decision to use the phrase “forum shopping,” decrying a patentholder’s litigation tactics as “forum shopping with a vengeance.”[1] Specifically, beauty-products manufacturer Helene Curtis Industries filed suit in the Southern District of New York, seeking a declaratory judgment that a patent held by competitor Procter & Gamble was invalid. But Procter & Gamble preferred to litigate in Texas and so it filed a parallel patent infringement suit there.[2] In an extraordinary order, Judge Kaufman enjoined the parallel infringement suit, explaining that “there [wa]s nothing to be gained by a trial in Texas rather than here [in New York], and there is much which commends the conclusion that this forum will best serve the ends of justice.”[3]

It is remarkable how little seems to have changed, as patent-holding plaintiffs are still trying to get into Texas’s federal district courts. Judge Alan Albright of the Western District of Texas is known for his appetite for patent cases, having “openly solicited cases at lawyers’ meetings . . . and urged patent plaintiffs to file their infringement actions in his court.”[4] Judge Albright even adopted plaintiff-friendly procedural rules designed specifically to attract patent litigation.[5] And because of a quirk in the case assignment procedures in the Western District of Texas, Judge Albright could, until recently, guarantee patent plaintiffs that he—rather than any other judge in the Western District—would preside over their cases.[6] Hence, Judge Albright’s caseload—over 800 cases in 2021—encompassed nearly a quarter of all patent cases filed nationwide.[7] Indeed, Judge Albright remains the most popular patent judge in the nation.[8]

But what about the rest of Judge Albright’s docket? Some scholars have examined Judge Albright’s controversial methods for attracting patent plaintiffs—i.e., his “forum selling” conduct.[9] Others have looked at his record in certain patent appeals before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit.[10] But no one has considered whether this deluge of patent cases affects Judge Albright’s consideration in, say, criminal or civil rights matters. Patent cases, after all, can be difficult, as they tend to be complicated and time intensive—perhaps leaving less time for these other sorts of cases (especially for those judges, like Judge Albright, who have expressed a strong preference for patent cases). Hard cases might thus make bad law in more than one way.[11]

Hence, while Judge Albright’s practices have renewed debates about forum shopping (by plaintiffs) and forum selling (by judges),[12] these exchanges have overlooked an important constituency—litigants who have far less control over the forum in which their case is heard. Scholars and policymakers have debated the merits of, say, allowing patent plaintiffs to choose a seemingly favorable federal forum, but they have largely missed the possible effects of such en masse case migration on the rest of that forum’s docket (criminal and civil rights cases, for example).[13] In all, many examinations of forum shopping consider such conduct from a perspective that is internal to the case or claims that give rise to the conduct—e.g., does forum shopping undermine fairness for patent defendants, or does forum shopping improve the local procedural rules governing patent claims?[14] But these studies often overlook the external effects of forum shopping—the effects, for example, on the civil rights plaintiffs or criminal defendants in that forum.

We examine such externalities of forum shopping in this Article. Our analysis includes a novel empirical study of several district courts subject to what we call “forum crowding”—substantial caseload increases resulting from forum shopping, forum selling, and responses to such behavior. Specifically, we draw on the well-documented forum-shopping-related pathologies of patent litigation to assess and measure the possibilities for forum crowding.

This study draws from and builds upon two strands in the legal literature. One strand is the scholarship considering the equities of forum shopping. This literature examines the harms that can flow from allowing plaintiffs to select favorable fora as well as the benefits that can result from interjurisdictional competition for cases.[15] Our Article adds to this literature by expanding the scope of the concerns implicated by forum shopping to encompass forum crowding. Specifically, we focus on the effects of court congestion caused by substantial forum shopping on other unrelated cases and parties (that is, on cases other than those subject to such forum shopping). By isolating forum shopping from other potential causes of court congestion, our Article can strengthen the link from one to the other, explaining that the downstream effects of congestion (e.g., workload effects) may also result from forum shopping and selling.[16] Forum crowding thus represents a specific sort of court congestion, namely, congestion caused by excessive forum shopping (including forum shopping that is induced by forum selling).

The second strand is the growing literature examining workload effects on legal decision-making. In one leading study, Bert Huang examined the effect of a sudden influx of agency appeals on the scrutiny given by federal appeals courts in other, unrelated cases.[17] He found that busy appellate judges are more likely to defer to their colleagues on the district courts: as appellate workloads increase, so do affirmance rates. Looking outside the Judiciary, Michael Frakes and Melissa Wasserman have estimated the consequences of workload effects on patent quality, finding that when patent examiners are expected to process more patent applications (and hence have less time to review each individual application), they are more likely to issue a low-quality patent—i.e., a patent more likely to be later deemed invalid.[18] Our study adds to, and builds upon, this literature by examining the effect, at the federal district courts, of a sudden influx of patent cases on non-patent cases.

Our analysis finds that this forum crowding has had important, significant effects on both process and substance in the district courts. We find that when a forum gets crowded, some judges move more quickly through their respective dockets. On reflection, this may seem obvious: judges face various institutional pressures to ensure that cases do not languish for long, such as the six-month list,[19] and so must process individual cases in a crowded docket more quickly to stay on schedule.[20] One possible consequence of this result is that district judges, when moving quickly, take less time and care with each case. But another possible consequence is that busy judges are no less careful, they are simply more efficient. In order to discern which is more likely, we turn to appeal rates and reversal rates.[21]

Here, the study’s research design takes advantage of the unique structure of patent appeals. Practically every appeal in a patent case is diverted to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (rather than the regional federal appeals court). Accordingly, a flood of patent cases in, say, the Western District of Texas will have no effect on the docket in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.[22] We can thus compare appeal rates and reversal rates in non-patent cases without worrying that the relevant Court of Appeals’ work is itself affected by crowding.[23]

We find that decisions from crowded dockets are reversed more often.[24] And our qualitative examination of some of these district court procedures, orders, and decisions corroborates the view that cases on these crowded dockets can get short shrift.

Moreover, a closer look at the patterns in our results uncovers a nuanced story: are these reversal rates attributable to a judicial preference for commercial patent litigation over, say, criminal trials; or are they due to the squeeze on the most precious judicial resource—time—that accompanies these massive caseload increases? Our analysis suggests that both judicial preferences and resource constraints matter, particularly because preferences can drive how judges allocate their resources (bandwidth for cases, slots for law clerks, and so on). The upshot is that crowded dockets may yield lower-quality decisions when such crowding is associated with a judge’s preference for a certain kind of case.

This Article proceeds in three Parts.

First, we describe the debates regarding forum shopping and forum selling, both in general and as applied to patent cases in particular. While these developments are well trod, our telling focuses on the matters most pertinent to forum crowding, including the developments that inform our research design (most notably, the migratory patterns of patent plaintiffs: to the Eastern District of Texas, then north to the District of Delaware, and then (back) to the Western District of Texas).

Second, we describe the results of our study. We begin by describing our specific research design, including our methods for manually collecting and analyzing the data we present. We then present our findings regarding reversal rates, appeal rates, and overall time-to-termination alongside our interpretation of these findings—namely, that forum crowding seems to degrade decision quality, and that these effects are driven by judicial preferences for certain cases.

Third, we propose possible responses to these findings. We consider ways that courts should—or should be required to—force parties to account for the costs of their forum shopping conduct. Further, we examine procedural reforms to venue and transfer rules and to the Civil Justice Reform Act’s “six-month list” that address the externalities of forum crowding, both through the direct regulation of forum shopping and selling behavior and through changes that would cause forum shoppers to internalize these externalities. And, given our focus on patent cases, we consider the implications of our study to matters of particular importance to patent law, including the rise of agency adjudication as a substitute for litigation in the courts.

I.Forum Shopping, Forum Selling, and Forum Crowding

A. Forum Shopping

In general, forum shopping refers to strategic venue selection: litigants may choose a forum because it offers favorable decisional rules or preferred procedural practices, among other possibilities.[25] While such behavior may well date to the beginnings of our legal system—choosing a venue is, after all, one of the first steps to filing any lawsuit—the phrase “forum shopping” itself seems to have originated in response to Erie Railroad v. Tompkins. In a foundational article, Harold Horowitz described “forum shopping” as an “evil” spawned by the Supreme Court’s decision in Swift v. Tyson,[26] among other federal decisions.[27] Erie, then, was an attempt to reckon with that evil.[28] By mandating that a federal court exercising its diversity jurisdiction apply substantive state law, Erie eliminated many incentives for forum shopping between state and federal venues (i.e., “vertical” forum shopping): both venues must apply the same decisional rules, and so neither system—state or federal—offers an advantage over the other.[29] Erie, however, did little to address “horizontal” forum shopping, in which litigants seek out favorable venues from among the state or federal courts, on the view that one state or federal district court will offer favorable rules or practices.[30]

Concerns about forum shopping thus persist.[31] Specifically, forum shopping continues to present concerns about gamesmanship, legitimacy, and court congestion.

Critics of forum shopping note that the practice promotes gamesmanship, as litigants seek out venues that treat claims differently for no reason other than the court in which they are brought.[32] Justice Kagan, for example, highlighted Texas’s strategy of filing its challenges to federal programs in selected divisions of selected districts, thereby assuring itself of an audience that seems more receptive to its claims.[33]

The seemingly arbitrary differences (particularly, perhaps, in outcomes) between fora that lead plaintiffs to choose one venue over another may also seem to undermine the legitimacy of our legal systems. Indeed, several notable jurists have suggested that forum shopping “feeds the growing perception that the courts are politicized.”[34] Such concerns about legitimacy extend to questions of judicial power and jurisdiction. Forum shopping that causes courts to hear cases that might otherwise seem beyond their purview—a case, for example, filed in a California state court about a “Pennsylvania-manufactured airplane with Ohio-made propellers [that] crashed in Scotland”—gives rise to concerns over aggrandizement and the scope of the judicial powers.[35]

Such forum shopping can also pressure courts’ internal procedures and docket management strategies. For example, the Supreme Court’s decision in Piper Aircraft explained that the domestic exercise of jurisdiction would make “American courts, which are already extremely attractive to foreign plaintiffs . . . even more attractive . . . and further congest already crowded courts.”[36]

We do not mean to say that the story is all bad. Pamela Bookman, for example, has identified several “unsung virtues” of forum shopping.[37] She explains that forum shopping can help preserve access to courts (thereby promoting private enforcement) and that forum shopping produces competition among courts for cases that can lead to positive legal reform.[38]

Hence, while the conversation on forum shopping is more complicated than simply decrying the practice as an “evil” tactic,[39] the general consensus among courts, scholars, and policymakers seems to strongly disfavor the practice.[40]

Notably, this literature largely ignores certain externalities of forum shopping—namely, its possible effects on the rest of a favored forum’s docket. As noted above, Bookman considers possible positive externalities of forum shopping, such as desirable legal reform. And others have described possible negative effects, such as diminished confidence in the courts.[41] These are certainly externalities of forum shopping: they are a cost or benefit imposed on the courts that is largely unrecognized by plaintiffs seeking favorable fora. But these are effects of forum shopping on the judicial system generally, and as far as we can tell, no study has examined the effects of forum shopping on other pending cases.[42]

B. Forum Shopping and Forum Selling: A Study in Patent Litigation

1. The Migrations of Patent Litigation

The debates over forum shopping have had special application to patent cases for the better part of three decades. Assessing caseloads from 1995 to 1999, then-Professor (now-Chief Judge) Kimberly Ann Moore found that much patent litigation was concentrated in only a few districts, and that some of these districts—the District of Delaware and the Northern District of California, for example—carried a disproportionate load of patent cases (as measured against their share of civil cases generally). The District of Delaware, for example, was home to 0.3% of all federal civil cases, but home to 3.2% of all patent cases.[43] Similarly, the Northern District of California was responsible for 2.3% of all federal cases, compared to 9.1% of all patent cases.[44]

Such figures, however, pale in comparison to the concentrations of patent cases that resulted from forum shopping in later years. See Figure 1, below.

Figure 1: Share of Patent Cases by District (D. Del, E.D. Tex., W.D. Tex.), 2011–2021

As Figure 1 shows,[45] the Eastern District of Texas accounted for nearly half of all patent cases in 2015.[46] In 2019, the District of Delaware housed nearly one-quarter of all patent cases.[47] And in 2021, a single judge in the Western District of Texas was responsible for nearly one-fourth of the nation’s patent litigation.[48]

Such unusual shifts of large concentrations of patent cases are the consequence of two interrelated features: (1) the law governing venue in patent litigation; and (2) the “substantive and procedural differences among district courts in resolving patent cases.”[49]

We begin with the law. The statute governing venue in patent cases, 28 U.S.C. § 1400(b), provides that “[a]ny civil action for patent infringement may be brought in the judicial district where the defendant resides, or where the defendant has committed acts of infringement and has a regular and established place of business.”[50] In 1990, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit considered what it meant for a patent defendant to “reside” in a particular district.[51] Looking to a 1988 amendment to the general venue statutes,[52] the Federal Circuit reasoned that a corporate defendant could be understood to “reside” in “any judicial district in which it is subject to personal jurisdiction.”[53] And, given the relatively capacious boundaries of personal jurisdiction, this ruling meant that most companies operating in the streams of interstate commerce could be sued under § 1400(b) in almost any federal district court.[54] Hence, patent plaintiffs began to engage in so-called “horizontal” forum shopping,[55] seeking out district courts that seemed to offer a more favorable forum for their claims.

We thus turn next to interdistrict variation. In the late 1990s, for example, patent plaintiffs seemed to prefer districts that moved quickly (thereby minimizing their litigation costs), that resolved cases well before trial (often insulating their patents from being found invalid), and that generally seemed to offer the “greatest chances of success.”[56]

But modest differences across federal districts later metastasized into more significant variations, as some judges designed patent-specific procedures rules with the specific intent of luring patent plaintiffs to their districts.[57]

Consider the Eastern District of Texas: in 2007, that district was home to the largest concentration of patent litigation in the nation, responsible for about one-eighth of all such cases; in 2012, it housed about one-fourth of all patent litigation in the country; and in 2015, it accounted for nearly half.[58] How did the Eastern District of Texas come to be such a favored forum? Procedural innovation. Judge T. John Ward began by emulating some of the practices that led to some of the early, modest consolidation noted above: Judge Ward adopted, for example, rules mimicking the Northern District of California’s “patent local rules” that allowed such cases to move more quickly.[59] Other authors have suggested that juries in Marshall, Texas—familiar with disputes over oil and sensitive to property rights—were predisposed to ruling in favor of patentholders, thus leading patent plaintiffs to file claims there.[60]

In 2011, Judge Ward retired, and (now-Chief) Judge Rodney Gilstrap was appointed to his seat. As Jonas Anderson and Paul Gugliuzza explain, “[Chief] Judge Gilstrap adopted unique practices that made his courtroom even more appealing for patent plaintiffs, such as requiring defendants to seek his permission before filing a motion for summary judgment or a motion to invalidate a patent for lack of patent-eligible subject matter.”[61] Chief Judge Gilstrap also adopted special discovery rules—rules which expedited discovery, increasing settlement pressure on defendants—and he took further procedural steps to insulate patents from validity challenges.[62]

Most notably, the Eastern District of Texas employs a unique case assignment procedure. Six divisions comprise the Eastern District of Texas: the Beaumont Division, the Lufkin Division, the Marshall Division, the Sherman Division, the Texarkana Division, and the Tyler Division. While case assignment is ostensibly random, any randomness applies only within a division rather than across the entire district, subject to case assignment rules set out in standing orders by Chief Judge Gilstrap.[63] Under these orders, all patent cases filed in the Marshall Division were directed to Chief Judge Gilstrap.[64] And, notably, no venue rules govern the choice of a division within a district.[65] Hence, patent plaintiffs eligible to file in the Eastern District of Texas can simply select the Marshall Division in the court’s electronic filing systems, thus assuring themselves of a spot on Chief Judge Gilstrap’s docket.[66]

Such procedural innovations (together with this unique case assignment procedure) help to explain many plaintiffs’ decisions to file in the Eastern District of Texas. But what explains these judges’ decisions to create such patent-friendly rules? Greg Reilly and Daniel Klerman contend that the Eastern District of Texas—and Judges Ward and Gilstrap, in particular—engaged in a practice of “forum selling.”[67] In short, they created “pro-plaintiff law and procedures” in order to induce plaintiffs, who typically control questions of venue in non-contract cases (including many patent infringement cases),[68] to bring their litigation there.[69] And their hypotheses for this behavior, alongside those advanced by other scholars,[70] range from the innocuous to the worrying: Judge Gilstrap, for example, may do this in order to attract cases he finds interesting or that he perceives to be more prestigious (perhaps because of their high stakes and complex nature); or Judge Ward might have done this to benefit the local economy (e.g., the hotels, restaurants, copy shops, cafés, and local law firms that benefit from increased local litigation) or perhaps for more direct pecuniary gain (as Judge Ward’s son is a local patent attorney).[71]

The Eastern District of Texas’s power over patent litigation caught the Supreme Court’s attention. As early as 2006, Justice Scalia referred to the district as a “renegade jurisdictio[n]” presenting a problem in need of redress.[72]

In 2017, over ten years after Justice Scalia’s initial critique, the Supreme Court finally offered a solution by way of its decision in TC Heartland v. Kraft Foods.[73] Specifically, the Court’s decision in TC Heartland revisited the Federal Circuit’s 1990 venue decision (which, recall, construed an amendment to the general venue statutes as applicable to patent venue statutes, too).[74] The Court upended the Federal Circuit’s prior approach and held unanimously that the amendment to the general venue statute did not apply to the patent-specific venue statute.[75] Hence, after TC Heartland, it is no longer the case that corporate defendants in patent litigation are suable anywhere they are subject to personal jurisdiction.[76] Rather, such defendants could be sued only in their state of incorporation or where they have “committed acts of infringement and ha[ve] a regular and established place of business.”[77] The Court granted review in TC Heartland to address a problem of forum shopping,[78] and its decision was effective at blunting the effect of the Eastern District of Texas’s procedural innovations.[79]

Because the Eastern District of Texas could no longer properly house so much patent litigation, the District of Delaware temporarily became the new venue of choice. Why Delaware? Because many corporate defendants are incorporated in Delaware, for reasons well-developed in the corporate law literature (namely, Delaware is an attractive forum in which to incorporate).[80] Colleen Chien and Michael Risch correctly predicted that, in TC Heartland’s wake, “cases would primarily move to the District of Delaware,” estimating that it would take responsibility for about one-quarter of all patent litigation.[81] Indeed, the District of Delaware’s share of new patent cases grew to slightly more than one-quarter of all filings after TC Heartland, while the Eastern District of Texas’s share shrank significantly.[82]

The District of Delaware’s prominence would, however, prove to be short-lived, as the Western District of Texas quickly took its place. As noted, after TC Heartland, patent defendants could be sued in their state of incorporation or wherever they have “committed acts of infringement and ha[ve] a regular and established place of business.”[83] And many corporate patent defendants have established places of business in San Antonio or Austin where patentholders may allege acts of infringement.[84] The Western District of Texas, which encompasses both cities,[85] thus offers one possible alternate venue for many patent cases.

Patentholders could thus file in the Western District of Texas, even after TC Heartland. But why would they? Again, the answer lies in procedural innovation and case assignment rules. Judge Albright, appointed to the Western District of Texas in 2018, has (like Judges Ward and Gilstrap) promulgated several standing orders that speed patent cases along faster, stay aspects of discovery in ways that seem to favor patent plaintiffs over defendants, and limit early motions to dismiss on certain questions of patent validity.[86] Such procedural practices strongly favor patent plaintiffs (though Judge Albright has defended his practices as “party agnostic”[87]).

Judge Albright not only takes steps to ensure that cases come to him; he also helps to make sure they stay with him. As noted, Judge Albright has limited how defendants can challenge a patent’s validity during a case’s early phases. Consequently, defendants might prefer to challenge these patents before the Patent Office, which offers a comparatively quick and cheap agency adjudication of a patent’s validity (known as inter partes review).[88] Most district judges stay patent litigation during the pendency of these agency reviews.[89] This is because an agency decision finding the patent invalid can quickly end the parallel litigation. But Judge Albright employs a different tack, instead often scheduling aggressively optimistic trial dates in order to dissuade the Patent Office from undertaking review at all.[90]

Judge Albright is similarly disinclined to grant motions to transfer cases to other venues, sometimes even in cases where the relevant factors evince a “striking imbalance favoring transfer.”[91] Indeed, the Federal Circuit has issued repeated writs of mandamus in many of these cases, sometimes finding Judge Albright’s decisions to deny transfer practically indefensible.[92]

Judge Albright’s popularity with patent plaintiffs has proved persistent. Until July 2022, the Western District of Texas employed a case assignment procedure akin to that of the Eastern District of Texas: case assignment was random only within a division, rather than across an entire district.[93] And because Judge Albright is the only member of the Western District’s Waco Division,[94] a patent plaintiff who filed in the Waco Division knew that Judge Albright would preside over her case. But in July 2022, the Chief Judge of the Western District, in an apparent response to critiques of Judge Albright,[95] unsuccessfully attempted to reform these assignment procedures.[96] And while Chief Judge Alia Moses, who recently succeeded Chief Judge Orlando Luis Garcia, has kept these reforms in place, Judge Albright remains the most popular patent judge in the nation.[97] In short, forum shopping in the Western District of Texas has proved sticky and resistant to efforts to dislodge it.

2. Evaluating Patent Forum Shopping

One obvious question raised by these patterns of patent case migrations is whether such dramatic movements are normatively desirable. Some commentators have characterized this forum shopping as an “evil” to be contained.[98] As with the more general literature on forum shopping, the literature on patent forum shopping typically focuses either on the distortions that result from plaintiff-friendly practices (e.g., gamesmanship-related concerns) or on the systemic implications that forum shopping has for the judiciary generally (e.g., legitimacy-related concerns).[99] On the former, some scholars have explained that plaintiff-friendly procedural rules—designed, for instance, to solicit patent cases—lead to “inefficient distortions of substantive law.”[100] On the latter, some commentary notes the possibility that forum shopping will diminish the public’s confidence in the courts or in the patent system.[101] Others, however, have a more sanguine view, contending that such procedural innovation may offer some benefits to our systems of patent litigation.[102] Overall, the debates about forum shopping in patent cases reflect debates about forum shopping more generally.

Scholars have primarily regarded patent forum shopping as undesirable: most think that the practice is more harmful to the courts and to our patent system than it is helpful to improving the mechanics of patent litigation. Judge Moore, for example, has suggested that forum shopping is “normative[ly] evil” because it “thwarts the ideal of neutrality in a system whose objective is to create a level playing field” for dispute resolution, thereby “erod[ing] public confidence in the law.”[103] She also notes that forum shopping gives rise to increased litigation costs (for example, travel to inconvenient locales or costs associated with motions to transfer) and that patent forum shopping may well undermine the innovation-inducing purposes of the patent franchise.[104] In later work, other scholars have echoed these concerns. Jonas Anderson, Paul Gugliuzza, and Jason Rantanen, as well as Greg Reilly and Daniel Klerman, have all remarked on the tendency of such forum selling and shopping both to undermine fairness and legitimacy and to increase the costs associated with venue-related disputes.[105] And these scholars have emphasized that these concerns are especially pronounced where plaintiffs are engaged in judge shopping beyond mere forum shopping.[106] In all, these critiques echo the concerns, noted above, about gamesmanship and legitimacy.[107]

Some scholars, however, have emphasized the benefits that may accrue from such forum shopping. Specifically, such commentary reflects the possibility that forum shopping can lead to positive legal reform. Jeanne Fromer, for example, has advanced a nuanced view of patent forum shopping. Though she ultimately concluded that, on net, forum shopping seems to do more harm than good, she noted the possibility that the interdistrict competition occasioned by forum shopping could “foster[] a race to the top . . . [that] cause[s] district courts to develop useful rules.”[108] She also suggested that local case concentration can give rise to both legal and substantive expertise—i.e., familiarity with both patent law and the actual (patented) technologies underlying local industries.[109] And more favorably still, Xuan-Thao Nguyen concluded that patent forum shopping leads to adjudication by “reasonable and fair” judges who are “knowledgeable, welcoming, and organized,” particularly because they have adopted a series of efficiency-enhancing and cost-saving local rules that reflect a “customer-oriented approach.”[110]

But both these sets of scholars—those who think that forum shopping is, on net, good for our systems of patent litigation, as well as those who think it is deleterious—have overlooked the effects of forum shopping in patent cases on the non-patent cases, and non-patent litigants, in that forum. Xuan-Thao Nguyen, noted, for example, that forum shopping allows patent plaintiffs to avoid districts that are “burdened with criminal cases.”[111] But criminal defendants in, say, Waco, Texas can hardly avoid a district burdened with patent cases.[112] Habeas petitioners and civil rights plaintiffs are similarly stuck.[113]

Is there any reason to worry about the influx of patent cases on the non-patent cases in, for example, Judge Albright’s courtroom? So far, we have very little evidence to say. We have found no study, either in the patent literature or elsewhere, that has closely examined the effects of forum shopping on other unrelated pending cases. We turn to such an examination next.

II. The Effects of Forum Crowding

These migrations of patent litigation—into the Eastern District of Texas, then out of Texas to Delaware, and then back to the Western District of Texas—offer an opportunity to study the effects of forum crowding on other cases, such as criminal and civil rights cases. What happens when a district judge is suddenly inundated by an influx of technical and typically complex cases?

Judge Edwards has written about this problem from the perspective of the federal appeals courts: “The bigger the dockets, the less time we spend on the difficult cases and the more mistakes we make.”[114] Judge Wald has also written about how “time and docket pressures” may cause a judge to rely on doctrines such as waiver or forfeiture (rather than take a close look at a claim’s merits).[115]

Some scholars, moreover, have noted the effects that docket congestion can have on litigation delay[116] and on public access to the courts,[117] while more recent scholarly examinations of workload effects on legal decision-making echo Judge Edwards’ view that docket congestion can affect outcomes. As noted above, Bert Huang finds that docket pressures at appeals courts can cause appellate judges to apply only “lightened scrutiny” to the decisions of their trial court colleagues.[118] Melissa Wasserman and Michael Frakes similarly found that patent examiners with higher workload expectations review patent applications less carefully, thereby granting more low-quality patents.[119]

We add to that literature here by examining the effects of the substantial swings in patent cases among the Districts of Delaware, Eastern Texas, and Western Texas on the other cases in those venues. We begin by describing our study design, and then move on to presenting the results of that study.

A. Measuring Forum Crowding

1. Defining Crowded Fora

We began by identifying the districts and judges that faced relatively more crowded dockets (as well as when such crowding occurred) in order to identify our treatment and control study periods. Unsurprisingly, the series of legal and procedural shifts described above guided our approach. We emphasize that our measure of forum crowding is relative, not absolute—that is, we sought out (for example) time periods of comparatively higher and lower concentrations of patent cases to determine whether those changes corresponded to, say, changes in indicia of decision quality, such as reversal rates.

We focus on two major developments, giving rise to three comparison sets.

First, the Supreme Court’s decision in TC Heartland presents a unique opportunity to measure the effects of forum crowding on decision quality in the Eastern of District of Texas and the District of Delaware, whose crowding is the consequence of two very different sources (forum selling and changes in venue rules, respectively).[120] In order to concentrate attention on the effects of forum crowding and to reduce the risks that other developments confound our results, we focused our study to the two years immediately preceding and following TC Heartland.[121] Indeed, the District of Delaware was near the nadir of its popularity among patent plaintiffs in 2015 and 2016, just before the Court’s decision in TC Heartland, when it accounted for 9% and 10% of all patent cases, respectively.[122] And the District of Delaware was the most popular patent venue in the two years immediately following TC Heartland, shouldering 24% and 28% of the national load in 2018 and 2019 respectively.[123] We thus treated the District of Delaware as non-crowded from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2016, and as crowded from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019.[124]

By contrast, the Eastern District of Texas actively solicited patent cases in the two years immediately before TC Heartland, accounting for about 40 to 45% of all patent cases, and saw its share of patent litigation wane drastically in the two years immediately following that decision.[125] Hence, we treated the Eastern District of Texas as crowded from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2016, and as non-crowded from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2019.[126]

Moreover, because judicial districts can vary over time in ways that would affect our results—judges retire while new judges come on the bench, leading to changes in judicial experience and, perhaps, judicial ideology—we further narrowed our analysis to consistent sets of judges within each district. In particular, we used two criteria to select judges from the Eastern District of Texas and the District of Delaware. First, we identified judges whose service included the entirety of our selected timeframes, both to study the crowding effects on individual judges who faced both crowded and non-crowded dockets and to avoid confounding our results with variations in judicial ideology, temperament, or experience.[127] Second, we focused on judges who were responsible for a significant number of patent cases within their respective districts. Our study includes, for example, Chief Judge Gilstrap, who is among the judges primarily responsible for the Eastern District’s popularity among patent plaintiffs,[128] as well as Judge Stark, who was recently appointed to the Federal Circuit from the District of Delaware.[129]

In short, by selecting the busiest patent judges within the busiest patent districts, we focused our study on those courtrooms where forum crowding was the most pronounced and where we expected its potential effects, if any, to be most conspicuous. In all, our examinations of the Eastern District of Texas focused on Chief Judge Rodney Gilstrap and Judge Robert W. Schroeder III, and our examinations of the District of Delaware focused on Judges Richard G. Andrews and Leonard P. Stark.[130] Figure 2, below, visually depicts these crowded versus non-crowded comparisons.

Figure 2: Crowded and Non-Crowded Periods by Judge

Second, Judge Albright’s appointment to the Western District of Texas’s Article III bench offers an additional opportunity to examine the effects of forum crowding. As noted, the Western District of Texas saw a meteoric rise in patent filings beginning in 2019, and so we consider January 1, 2019, to June 1, 2022, the date we ended data collection, as crowded. This period coincides, unsurprisingly, with Judge Albright’s tenure on the bench, as he was confirmed in late 2018.

But because we treat nearly all of Judge Albright’s tenure on the bench as crowded, to whom or what should we compare his outcomes? We cannot compare a crowded Judge Albright docket to a non-crowded one. Instead, we compare Judge Albright’s metrics to those of his compatriots on the Western District of Texas who hear comparatively few patent cases. In particular, we selected two judges who were appointed at about the same time (late 2018 or early 2019) and by the same president (President Donald J. Trump) to help account for judicial experience and ideology: Judge Walter David Counts III and Judge Jason K. Pulliam.[131] Similar to Judge Albright, both Judge Counts and Judge Pulliam served as judges prior to joining the federal bench. Judge Counts, like Judge Albright, served as a Magistrate Judge for the Western District of Texas,[132] and Judge Pulliam served as a Justice on the Texas Fourth Court of Appeals.[133] Additionally, all three have served as active judges in the Western District of Texas for roughly the same amount of time, as each received their commissions in 2018 or 2019.[134]

Table 1: Crowded and Non-Crowded Judges, W.D. Tex.

| Judge | Status |

|---|---|

| Albright | Crowded |

| Counts | Non-Crowded |

| Pulliam | Non-Crowded |

Hence, of our three comparison sets, two are intrajudicial and intertemporal (that is, they compare metrics of a consistent set of judges over two different time periods) and one is interjudicial and intratemporal (that is, it compares different judges over a single time period). In all, these comparisons allow us to study the effects of forum crowding in two ways. First, we compare the metrics of a consistent set of judges on the Eastern District of Texas and the District of Delaware during periods of relative crowding to those of no crowding. Second, we compare the metrics of the judge experiencing crowding in the Western District of Texas to those who simultaneously experience no crowding in that same district. While this latter comparison offers less compelling evidence of the direct effects of forum crowding (as opposed to, say, the idiosyncratic behavior of one judge),[135] it allows us to examine some consequences of the specific phenomenon that is behind many contemporary complaints about forum shopping, and selling, in patent cases.

2. Data and Metrics

Having described our comparison sets, we turn next to describing our dataset, including our data sources and metrics for analysis.

Our data draws from three primary sources: the Federal Judicial Center, Lex Machina, and Westlaw. While we might have preferred to rely on a single source for all of our data and analysis, thus ensuring consistent definitions for, and treatments of, cases and their categorization,[136] we found that no single source provided a comprehensive set of docket-level information across all case types for a given judge. For example, Lex Machina provides a sophisticated set of tools for civil cases but contains no criminal case data. Conversely, the Federal Judicial Center’s Criminal Integrated Database provides comprehensive data on criminal dockets but no civil case data. And it offers only division-level information, rather than a judge-specific breakdown of cases. Moreover, while Westlaw included some features that proved particularly useful for tracking appeal outcomes and disposition dates, its methods of case categorization lacked the level of detail and consistency we required for other aspects of our analysis.

To measure the effects of forum crowding on decision quality, we collected information on non-patent cases. Our reason for excluding patent cases is simple: we want to distinguish the causes of crowding (i.e., patent cases) from their possible effects.[137] Consider, for example, the possibility that Judge Albright (or Judge Gilstrap) sought to attract patent litigation because of a passion for patent law and a belief that a particular application of patent doctrine is best for innovation policy. It may be, though, that Judge Albright’s vision for patent law is not shared by his colleagues on the Federal Circuit. And so the effect of Judge Albright’s forum crowding behavior (high reversal rates—due, perhaps, to an idiosyncratic view of patent law; or due, perhaps, to crowding effects) may be, in this hypothetical example, entangled with its cause (i.e., a desire to implement that idiosyncratic view). But this is not so for other cases, which provide a more reliable measure of the effects of this forum crowding. Hence, we collected information on non-patent civil and, where feasible, criminal cases. Moreover, within the civil case category, we also collected information about selected civil rights and habeas cases, defined to include claims arising under Section 1983, Bivens, or federal habeas corpus statutes.[138]

We focused our data collection efforts on three case-specific metrics: time-to-termination (i.e., the amount of time between a case’s filing and its final disposition); appeal rates (i.e., whether a given case was appealed, yielding an overall appeal rate calculation); and reversal rates (i.e., the outcomes of each of those appeals, yielding an overall reversal rate calculation).[139]

In selecting time-to-termination, appeal rates, and reversal rates as our metrics for analysis, we do not mean to suggest that these are the only relevant measures of forum crowding’s effects. For example, while time-to-termination measures may be suggestive proxies for judicial attention or procedural fairness, other more difficult-to-capture metrics, such as “bench presence,” may offer a richer metric.[140] And so we emphasize that our examination does not rely on bare statistics alone but also encompasses a qualitative examination of the practices of the judges in our dataset—Judge Albright’s practice, for example, of immediately referring nearly all of his non-patent cases to a magistrate judge in the first instance[141]—as well as a review of the underlying decisions and opinions themselves.[142] Indeed, we consider other metrics of decision quality, such as opinion length and detail, in our qualitative reviews of these decisions.

Likewise, we acknowledge some uncertainty over whether reversal rates are a perfect proxy for measuring decision quality, as relying on reversals may imply an assumption that, in a given reversal, the appeals court was correct and the trial court was not. But we mean no such implication and agree that correctness might be assessed on terms outside a court’s place in the judicial hierarchy. Hence, while we acknowledge these important epistemic questions, we rely on appellate outcomes for several other reasons: first, even if correctness might be measured on other terms, a reversal does suggest that the trial court’s decision was deficient—“improper or inadequate”—in at least one way; second, that deficiency gave rise to additional investments in the litigation process, and “a goal of the justice system is to reduce the need for appeals;” and third, reversal rates are consequently widely used in the literature as a proxy for decision quality.[143]

We turn next to a more detailed description of each of these three metrics.

3. Time-to-Termination

We collected time-to-termination information in part to test our hypothesis that busy judges would have to move through individual cases on a crowded docket more quickly.[144]

Lex Machina automatically calculates time-to-termination, computing it as the difference between the filing date of the case and the termination date of the case as recorded on PACER.[145] Hence, for civil cases (including civil rights and habeas cases), we used Lex Machina’s time-to-termination metric.[146] For criminal cases, we used the Federal Judicial Center’s Criminal Integrated Database. While this database does not offer judge-specific information, it does offer division-specific information—and some divisions, recall, house only one judge. Hence, we filtered the database by district and by office code (i.e., division[147]), in order to obtain time-to-termination information for the respective criminal dockets of Judges Gilstrap, Schroeder, and Albright (each of whom is the only judge in their division).[148] Like Lex Machina, we calculated the difference between the filing date and the disposition date.[149] And because we were unable to obtain comprehensive judge-level criminal case data for Judges Andrews and Stark in the District of Delaware and for Judges Counts and Pulliam in the Western District of Texas, we cannot report their time-to-termination metrics in criminal cases.[150]

4. Appeal Rates

As noted, we also collected information on how many cases are appealed. Some literature has used appeal rate data as a proxy for a litigant’s confidence in a district court decision.[151] Appellants may be likely to file only those appeals that they think they can win, or, at least, where they calculate its expected value to exceed its expected costs. Hence, as a decision’s quality decreases, the likelihood of appeal increases. And as decision quality in general decreases, appeal rates should increase in aggregate.[152]

While we collect and report on this metric, we share other scholars’ trepidation about its utility.[153] Appeal rates are the function of myriad variables, including confidence in the appealed decision, the ability to pay for the appeal, or the desire for finality. So it is not obvious that appeal rates will uniquely reflect litigant confidence in the district court’s opinion, as opposed to these other concerns.

Appeal rate information can also serve a distinct, but related, function: it can help alert for possible selection effects. For example, one might view an increase in reversal rates accompanied by a drop in appeal rates as suggestive of appeal selection and not decision quality. That is, the new reversal rate might be attributable to better appellant decision-making—i.e., better selection of the decisions that merit an appeal—rather than an overall effect on decision quality.

We calculate appeal rate metrics straightforwardly, dividing the total number of appeals taken by the number of district court dispositions during the study period.[154] We collect the total number of district court dispositions as described above (for calculating time-to-termination rates), using either Lex Machina or the Criminal Integrated Database. We collect the number of appeals taken using Westlaw’s appeal analytics tools.[155]

5. Reversal Rates

Finally, we calculated reversal rates to help assess decision quality. These measures are based on appeal outcomes for each judge during both crowded and non-crowded periods, relying, again, on Westlaw’s database.[156] More specifically, we retrieved all the appeals Westlaw identified as originating with the judges during our study period and divided those into three sets: criminal cases, non-patent civil cases, and patent cases.[157] As noted above, we excluded the patent appeals from our review.[158]

Indeed, our research design, emphasizing patent-related crowding, is uniquely suited to study reversal rate effects (as opposed to a design emphasizing crowding caused by some other sorts of cases). This is because patent cases have their own appellate pathway—patent cases are appealed to the Federal Circuit, while other cases are typically appealed to the relevant regional circuit (the Fifth Circuit in the case of Texas; the Third Circuit in the case of Delaware).[159] Hence, because patent cases are filtered out at the appellate level, we need not worry about any possible effects of appellate crowding; that is, an influx of patent cases will not yield an influx of patent appeals that may affect appellate outcome measures.[160]

We readily acknowledge that our approach leads, in some instances, to smaller sample sizes. Our analysis is limited to appealed cases from a select set of judges over a limited time period. But we emphasize that our study’s sample encompasses nearly the entire universe of opportunities to study this phenomenon. Because of their unique appellate pathway, patent cases present a rare opportunity to measure district court effects by reference to appellate outcomes; and TC Heartland is a unique “policy shock” that caused a substantial change to patent plaintiffs’ litigating behavior. On balance, we think the benefits of limiting our view to a consistent set of judges, and to the time period most immediately adjacent to TC Heartland (namely, reducing the likelihood that our results are affected by confounding factors), offset concerns about the smaller sample size. Furthermore, we accompany our quantitative analysis with a corroborating qualitative examination of these courts’ decisions and procedures.

After identifying and categorizing the relevant appeals, we recorded the outcome (affirmed, or not) for each case. Affirmances include any decision affirmed in its entirety, any appeal that was dismissed, and any writs of mandamus that were denied.[161] Reversals include decisions that were reversed, vacated, or remanded, whether in whole or in part,[162] as well as petitions for writs of mandamus that were granted. And outcome measures are reported as a percentage of all appeals. For example, twenty-four of the non-patent cases that Judge Stark decided between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2016, were appealed to the Third Circuit. Of those, twenty-two were affirmed. Hence, Judge Stark’s affirmance rate during this non-crowded period was 91.7% (or twenty-two out of twenty-four).

B. Results and Analysis

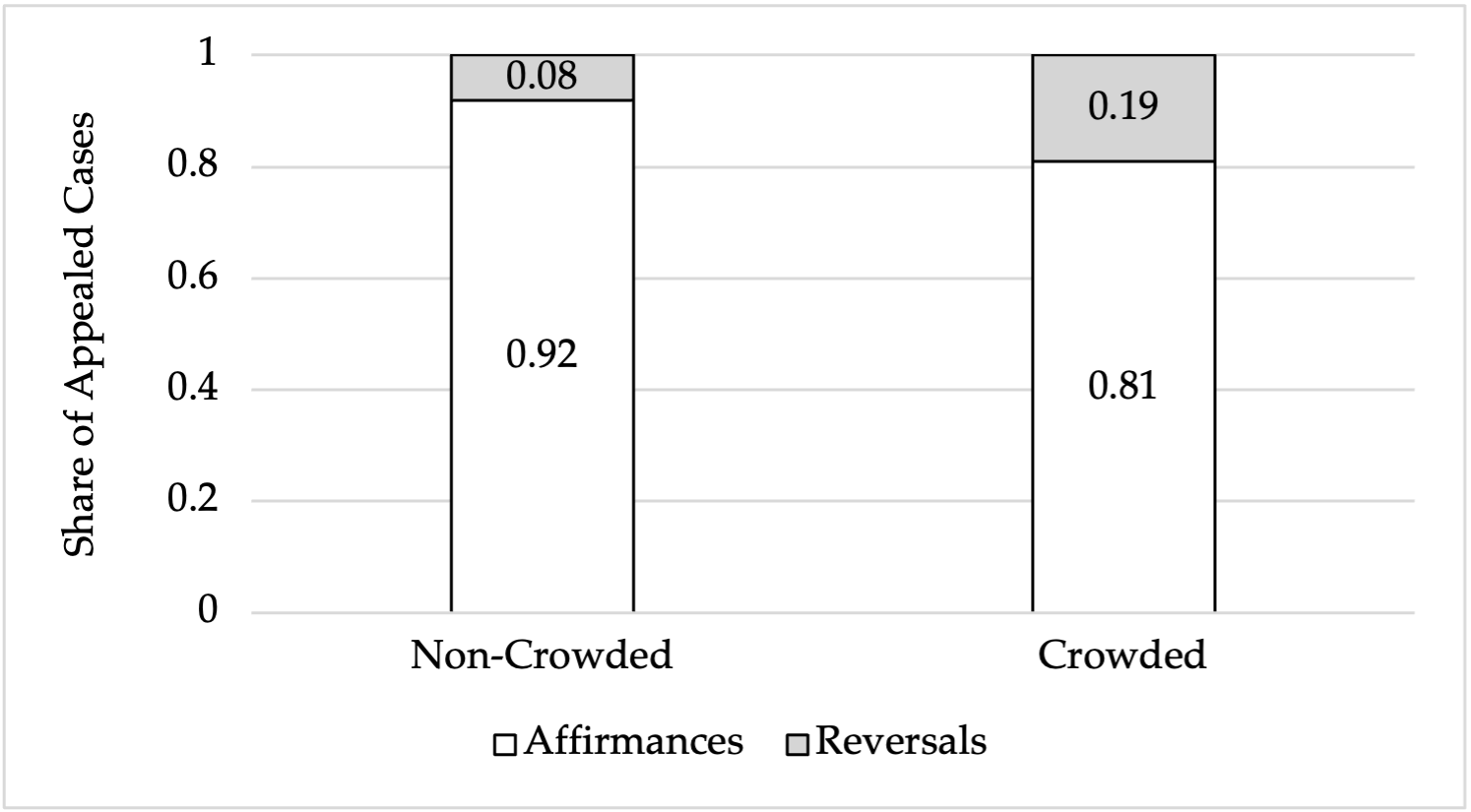

We present our results and analysis below. Our analysis of crowded and non-crowded dockets in the Eastern District of Texas, the District of Delaware, and the Western District of Texas suggests a stark pattern: when judges crowd their dockets, decision quality suffers. We emphasize, moreover, that our results are founded on the entire population of relevant cases and satisfy other measures of statistical significance.[163]

We begin by presenting our reversal rate and appeals rate data, alongside our qualitative review of decisions in these dockets, in order to describe the relationship between crowding and decision quality. We find that quality is lower when crowding is higher. We then turn to the question of mechanism: why, exactly, are crowding and decision quality related? Here, we find that our more granular results, alongside our time-to-termination statistics, help to reveal the extent to which judicial preferences matter.

1. Decision Quality

Our examination of the quality effects on crowding starts with our reversal rate metric. These measures suggest that decisions rendered on crowded dockets have been reversed more frequently than those on non-crowded dockets.

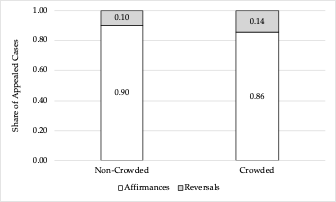

We begin with the Eastern District of Texas and the District of Delaware. Recall that these comparisons examine the behavior of a consistent set of judges over time, namely, before and after TC Heartland, which caused a vast number of cases to shift from the Eastern District of Texas to the District of Delaware.[164] But the sources of crowding in each of these districts is very different: in the Eastern District of Texas, it is forum selling; in the District of Delaware, it is the change in venue rules occasioned by TC Heartland.

Figure 3: Reversal Rates, Eastern District of Texas (All Cases, n=18)

Figure 4: Reversal Rates, District of Delaware (All Cases, n=158)

In the Eastern District of Texas, reversal rates during periods of crowding are substantially higher than during periods of less crowding.[165] The District of Delaware evinces a similar, if less pronounced, trend. While we revisit the differences in the strength of the trend in the next Section,[166] it is worth remarking on how this effect is consistent across various classes of cases.[167] For example, in civil rights and habeas cases, reversal rates are starkly higher in both the Eastern District of Texas and the District of Delaware during periods of forum crowding.

Figure 5: Reversal Rates, Eastern District of Texas (Civil Cases, n=17)

Figure 6: Reversal Rates, District of Delaware (Civil Cases, n=123)

Figure 7: Reversal Rates, Eastern District of Texas (Civil Rights & Habeas Cases, n=6

Figure 8: Reversal Rates, District of Delaware (Civil Rights & Habeas Cases, n=20)

Moreover, we do not believe that the results illustrated above result from changes in the body of appealed cases. As noted above, reversal rates, if accompanied by changes to the appeal rate, might be ascribed to a more careful selection of cases for appeals—i.e., putative appellants may improve their selection of cases for appeal, bringing only the one they are likely to win, and forgoing others. But here, the appeal rates appear rather steady over our study periods, as demonstrated in Tables 2 and 3. Hence, changes in the appeal rate cannot account for these differences in the reversal rate.

Table 2: Appeal Rates, Eastern District of Texas (Civil Cases)

| District | Crowded Rate(%) | Non-Crowded Rate(%) |

|---|---|---|

| E.D. Tex. | 1.5 | 1.4 |

Table 3: Appeal Rates, District of Delaware (Civil Cases)

| District | Crowded Rate(%) | Non-Crowded Rate(%) |

|---|---|---|

| D. Del. | 3.4 | 3.3 |

In all, the overall trends at the district level across both the Eastern District of Texas and the District of Delaware are consistent with the view that forum crowding affects decision quality. Indeed, the difference between reversal rates during crowded and non-crowded periods is significant.[168] This result suggests that forum crowding adversely affects decision quality. These findings are further corroborated by our qualitative examination of the orders and decisions issued by these judges during these periods.[169]

We might, for example, look at two similar cases—two appeals of a bankruptcy court ruling in a proceeding regarding individual debtors—before Judge Gilstrap (of the Eastern District of Texas), one decided during a crowded period and one not.[170] Judge Gilstrap presided over both cases without the assistance of a magistrate judge, and he affirmed the Bankruptcy Court’s rulings in both cases. However, the order rendered during the crowded period cites no caselaw and is barely a page in length, while the order from the non-crowded period is more than five times longer and features more thorough background and discussion sections (including citations to caselaw, the docket, and relevant statutes).[171]

Two of Judge Gilstrap’s employment cases—again, one before TC Heartland and another after—further highlight this phenomenon.[172] Both cases involved lawsuits brought by employees against their employers under the Fair Labor Standards Act. In both cases, Judge Gilstrap granted the defendant employers’ motions to transfer venue against the plaintiff employees’ wishes. The order granting the motion to transfer venue from the crowded period, however, is a little under two pages and offers no analysis of the parties’ arguments. The order filed during the non-crowded period is almost four times as long and provides an in-depth discussion of the applicable legal standard, the relevant public and private interest factors, and the parties’ claims.

Indeed, a more general review of Judge Gilstrap’s case dockets before and after TC Heartland suggests that, during periods of crowding, Judge Gilstrap’s orders are far less frequently accompanied by explanatory memoranda, and even when such memoranda are included, they tend to be less comprehensive. Such markers of “judicial effort” per case reflect not only on decision quality, but also have important implications for public reasoning and procedural fairness values in judicial decision-making.

We can find similar examples from the District of Delaware. During Judge Stark’s non-crowded period, he issued a twelve-page order granting in part and denying in part cross-motions for summary judgment on a plaintiff’s appeal of her denial of disability insurance benefits under the Social Security Act (SSA).[173] Judge Stark spent four pages of his opinion in Cannon v. Colvin on the factual background, describing each of the plaintiff’s injuries in detail.[174] And he spent another four pages on his discussion applying the relevant law to the facts, largely regarding the appropriate weight to be given to expert testimony.[175] In contrast, during his crowded period, Judge Stark considered a similar case in an analogous posture: cross-motions for summary judgment on a plaintiff’s appeal of her denial of disability insurance benefits under the SSA.[176] This eight-page opinion, which reached the same legal conclusion based on the same issues as Cannon, spent only two of those eight pages applying the relevant law to the weight of the expert’s testimony.[177] Notably, the order spends only one short paragraph discussing the justifications for the administrative law judge’s choice not to credit the treating physician’s records.[178] But the same issue in the non-crowded opinion spans almost three pages, and includes copious citations to the administrative record.[179]

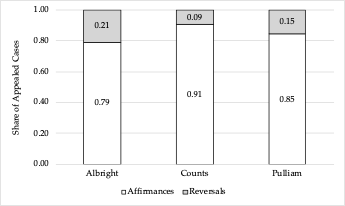

Similar results attend to our quantitative and qualitative assessments of the Western District of Texas, lending further support to the inference that crowding affects quality. Judge Albright’s track record before the Fifth Circuit features a substantially higher reversal rate compared to that of his contemporaries in the Western District of Texas. Figure 9, for example, implies that Judge Albright was reversed (or remanded, etc., in whole or in part) more than twice as often as Judge Counts and 1.4 times as often as Judge Pulliam.

Figure 9: Reversal Rates, Western District of Texas (All Cases, n=232)

Figure 10: Reversal Rates, Western District of Texas (Civil Cases, n=62)

Moreover, Judge Albright’s governing standing orders assign nearly all civil matters to magistrate judges, save for only a few exceptions: patent cases, as well as habeas corpus, Section 1983, and Bivens cases (i.e., our category of “civil rights and habeas” cases[180]).[181] The results illustrated in Figures 9 and 10 are further exaggerated when we narrow focus to only those cases that do not automatically benefit from an initial review by a magistrate judge.[182]

Figure 11: Reversal Rates, Western District of Texas (Civil Rights & Habeas Cases, n=24)

As Figure 11 demonstrates, Judge Counts and Judge Pulliam have a perfect record in habeas, Section 1983, and Bivens cases, whereas Judge Albright—who reserves only these cases for his initial first review (alongside his extensive patent docket, of course)—is reversed in more than one-quarter of these cases, suggesting an effect on decision quality in his comparatively crowded docket.[183]

These results, moreover, are reflected in the Western District of Texas’s appeal rates data. As noted above, we are somewhat unsure that appeal rate serves as a clear signal of decision quality, given that the decisions to appeal are informed by a wide range of factors beyond the mere likelihood of error.[184] But these appeal rate measures offer some additional soft support for a view that crowding affects decision quality, at least in the Western District of Texas, where Judge Albright’s non-patent civil cases were both appealed more frequently and reversed more frequently than those of his judicial colleagues. These measures thus also strongly undercut the possibility that differences in the reversal rate are attributable to differences in the selection of cases for appeal.

Table 4: Appeal Rates, Western District of Texas (Civil Cases)

| Judge | Status | Appeal Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Albright | Crowded | 5.4 |

| Counts | Non-Crowded | 2.2 |

| Pulliam | Non-Crowded | 2.1 |

Again, these results are even more pronounced when narrowed to only those cases for which Judge Albright bears primary responsibility (i.e., excluding those cases referred to a magistrate for a first review).

Table 5: Appeal Rates, Western District of Texas (Civil Rights & Habeas Cases)

| Judge | Status | Appeal Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Albright | Crowded | 42.9 |

| Counts | Non-Crowded | 5.7 |

| Pulliam | Non-Crowded | 7.3 |

Judge Albright’s performance in criminal cases (cases which are initially referred to a magistrate for pre-trial matters, among other things[185]) similarly lags behind his peers. As Figure 12 illustrates, the Fifth Circuit reversed Judge Albright’s criminal decisions more than twice as often as it reversed Judge Counts, while Judge Pulliam has not been reversed in any criminal matter.[186]

Figure 12: Reversal Rates, Western District of Texas (Criminal Cases, n=170)

And, as in the Eastern District of Texas and the District of Delaware, a more qualitative review of some of the opinions in these sets of cases reinforces the finding that forum crowding affects decision quality.

In Judge Albright’s first year as the nation’s busiest patent judge, he presided over Antonio Gardner’s federal criminal proceedings.[187] One day after Gardner filed a motion to withdraw his guilty plea, Judge Albright, “in a one-word order, denied his request to withdraw the plea, without an evidentiary hearing,” later sentencing Gardner to a twenty-year prison term (followed by six years of supervised release).[188] On appeal, the Fifth Circuit chided Judge Albright for failing to adequately analyze Gardner’s arguments and for offering no reasoning beyond “a single-word order—‘DENIED.’”[189] The terseness of Judge Albright’s consideration in this case (and others) offers further evidence of a possible effect on decision quality.[190]

Consider, too, the Fifth Circuit’s decision in Alvarez v. Akwitti.[191] There, Alvarez asked Judge Albright to hear his pro se complaint, alleging that prison officials were putting him at risk of retaliation from a “sexually violent predator inmate.”[192] Judge Albright dismissed the complaint sua sponte, even before the defendant warden had filed a response. The Fifth Circuit reversed and remanded, explaining that Judge Albright’s “failure to consider the entirety of Alvarez’s allegations” required a closer look and reminding Judge Albright of his obligations to pro se applicants in particular.[193]

We cannot, of course, say conclusively that these results are not the byproduct of some idiosyncrasy in Judge Albright’s approach to civil rights and criminal cases. It may well be that Judge Albright simply approaches these cases differently from his compatriots on the Western District’s bench.[194] Nevertheless, our appeals outcome results in the Eastern District of Texas and District of Delaware (which, recall, assess trends over a consistent set of judges in each venue) offer stronger evidence for the view that forum crowding matters. And our qualitative reviews of decisions from those districts reinforce the finding that forum crowding matters—and that it matters for values that sound not only in “correctness,”[195] but also in such concerns as public reasoning,[196] procedural fairness, and judicial legitimacy.

2. Explaining Forum Crowding’s Effects

There are at least two possible explanations for why forum crowding—and forum crowding resulting from the sort of patent-related forum-shopping and forum-selling conduct described above—may adversely affect decision quality.

One possibility is that forum-selling conduct reflects judicial preferences: Judge Albright and Chief Judge Gilstrap seem to strongly prefer patent cases.[197] And so, given the opportunity to choose to work on one among a wide range of patent cases or something else, we might expect them to prefer patent cases (and, perhaps, to neglect the rest of their dockets). If this were so, then we would expect a stronger effect among the judges who seem to prefer patent cases (a preference evinced, perhaps, by forum selling).

A second, alternate (and potentially complementary) possibility is encapsulated in Judge Edwards’s view that bigger dockets give judges less time to work on cases, thereby increasing the likelihood of error.[198] This hypothesis is more indifferent to judicial preferences, focusing instead on a court’s finite bandwidth or capacity for cases. Under this view, forum-crowding-related capacity constraints affect decision quality no matter whether the cause of such crowding is internal to the forum (e.g., a consequence of forum-selling conduct) or external (e.g., a byproduct of the Court’s decision in TC Heartland).[199]

Our results are suggestive of both possibilities. On the one hand, we see decision-quality effects across both sets of districts—those whose active solicitations of patent litigation seem to suggest a preference for such cases (i.e., the Eastern and Western Districts of Texas), as well as those where forum crowding was the mere byproduct of TC Heartland’s revised interpretation of the governing venue statute (i.e., the District of Delaware). But, on the other hand, the strength of the trend is more pronounced in those districts where there is an apparent preference for patent litigation (evidenced by forum selling). And so, while we ultimately conclude that both judicial preferences and resources seem to have a role to play in this story, it is worth further unpacking our results and their relationship to these possible mechanisms.

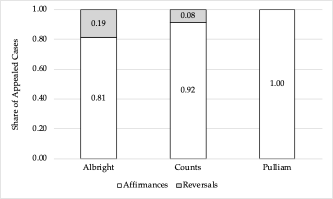

We begin by trying to discern the source of the disparity in the strength of the forum-crowding effects between the District of Delaware and the Eastern District of Texas. Specifically, we disaggregate the district-level results into more judge-specific results. Here, we uncover something possibly surprising. While Judge Stark’s reversal rate more than doubled when his docket was crowded, Judge Andrews, interestingly, did better on appeal to the Third Circuit during the more crowded years immediately following TC Heartland.

Figure 13: Reversal Rates, Judge Stark (All Cases, n=72)

Figure 14: Reversal Rates, Judge Andrews (All Cases, n=87)

We might conclude from these results that we have resolved our mechanism puzzle. After all, Judge Stark was, as noted, elevated to the Federal Circuit after our study period. This appointment might signal a substantial interest in patent cases. Judge Stark might have, for example, developed a preference for patent cases after having been exposed to so many of them as a consequence of TC Heartland (or, perhaps, he always preferred patent cases, but not so much as to engage in forum selling). These individuated results cleanly cleave those judges who have evinced some preference for patent cases (either in their forum-selling conduct or in their subsequent career paths) from those who have not, with negative effects on decision quality in only the former group.[200] But Judge Stark’s promotion, while suggestive of a preference for patent litigation, is less dispositive of such an inclination (as compared to, say, Judge Albright’s open solicitations to patent plaintiffs).[201]

Hence, we turn to our time-to-termination results in order to assess the extent to which capacity matters. Here, we find that both Judge Stark and Judge Andrews took less time to resolve non-patent civil cases during the crowded study period than during the non-crowded study period.[202] Stated similarly, forum crowding constrained the time they could dedicate to each case, especially given that judges often hesitate from—and are admonished against—letting cases languish for too long.[203] These effects were far more pronounced for Judge Stark, whose median time to termination went from 460 days before TC Heartland to only 181 days afterward—a decrease of over 60%. By contrast, Judge Andrews, who was working rather quickly to begin with, saw his median time-to-termination reduced by a more modest amount.

Figure 15: Time to Termination, Judge Stark (Civil Cases, n=939)

Figure 16: Time to Termination, Judge Andrews (Civil Cases, n=869)

Judge Andrews, moreover, appears to have been more strategic in allocating his time to cases. Our closer look at some of the orders and cases underlying these results suggests that Judge Andrews is the only judge in the District of Delaware to invariably include an option to refer a case to alternative dispute resolution on his scheduling order form, and he seems to have used that procedure with some regularity.[204] Hence, some cases settled quickly, and Judge Andrews accordingly spent less time on them; other cases, however, still required more attention. Judge Stark, by contrast, reduced the time he spent on all non-patent civil cases, no matter whether they ended with a settlement or some other judgment.[205] In all, these time-to-termination results—which can be understood to estimate available judicial resources or capacity—mirror our decision-quality results: where judicial capacity is more tightly constrained (relative to a non-crowded baseline), effects on decision quality are stronger.[206]

Our Western District of Texas results are similar: Judge Albright moved through his civil docket the most quickly and had the highest reversal rate of these judges, while Judge Counts took the most time with each civil case and had the lowest reversal rate.[207]

Figure 17: Time to Termination, Western District of Texas (Civil Cases, n=1,552)

But our time-to-termination results in the Eastern District of Texas are more surprising: both Chief Judge Gilstrap and Judge Schroeder take slightly more time per case during periods of crowding, as Figure 18 (and Appendix Figures 6–9) illustrate.

Figure 18: Time to Termination, Chief Judge Gilstrap (Civil Cases, n=636)

How could this be? As noted above, judges face significant institutional pressure against drawing cases out; but here, the Eastern District appears to be doing exactly that—taking longer to resolve cases, even as its docket grows.[208] Our hypothesis is that the Eastern District of Texas was simply too busy. Recall that, during years of crowding, the Eastern District was responsible for nearly half of all the nation’s patent cases.[209] Facing such an incredible workload, Judges Gilstrap and Schroeder may have had no choice but to let some cases languish for longer. We return to this hypothesis in the next Part. For now, it suffices to note that these results make it harder to discern whether the Eastern District of Texas in fact dedicated less capacity to each nonpatent civil case during years of crowding (compared to years of less crowding).[210]

Hence, the relationship between judicial capacity and decision quality does not align quite as neatly as the relationship between judicial preferences and decision quality. Constraints on judicial capacity—reflected in less time dedicated to each case—correspond roughly to increases in the reversal rate in the District of Delaware and the Western District of Texas, while our time-to-termination results from the Eastern District of Texas are harder to interpret. Meanwhile, every judge who has evinced a preference for patent cases seems to neglect the rest of their docket during periods of crowding (measured by reversal rate), and every judge who has evinced no such preference seems to be affirmed at the same—or better—rates during periods of crowding.

In short, these results corroborate the view that judicial preferences matter: we see negative effects on decision quality only among those judges who have evinced a preference for patent litigation, either through their forum selling conduct or through other choices.

But we are also mindful of the fact that our time-to-termination results in both the District of Delaware and the Western District of Texas also correlate, roughly, to our decision-quality results, while the Eastern District’s time-to-termination statistics are somewhat perplexing. And so we do not discount the oft-repeated view, voiced by judges with relevant experience, that resource constraints affect the care and attention that judges can give to the cases before them.

This is particularly so because we might understand these two hypotheses—one about judicial preferences and another regarding capacity and bandwidth—as complementary. Judicial preferences matter. And they might matter, especially, to how judges allocate their time and other resources. We can uncover some evidence for this hypothesis in the way these judges allocate other resources, such as in clerk hiring practices, or in the assignment of matters to magistrate judges. Judge Gilstrap, for example, prefers to hire law clerks with expertise relevant to patent litigation.[211] But such hiring practices may mean that these chambers lack familiarity with other bodies of doctrine. Similarly, Judge Albright has explained that the magistrate judges in the Western Division of Texas help him stay “afloat” with his patent cases by “taking on more duties from [his] docket” such as “felony pleas of guilt,”[212] while Judge Albright keeps other matters—such as all patent cases—for himself. In short, Judge Albright and Judge Gilstrap, perhaps among others, allocate their resources to focus on the cases they prefer—patent cases—to the seeming exclusion of other matters.

III. Reforming Forum Crowding

When judges crowd their dockets, the quality of their judicial decisions seems to decline. We consider these consequences of forum crowding to be among the externalities of forum shopping and, especially, forum selling, given our view that judicial preferences are a primary driver of the decision-quality effects noted above.[213] Such preferences—and the forum crowding that they give rise to—have real effects on real litigants. Consider, again, Antonio Gardner, whose criminal case sat on Judge Albright’s docket in 2020. In cases like his, the difference between a crowded forum (crowded because of forum selling) and a non-crowded one—one, perhaps, with more capacity or criminal law expertise—could be the difference not only between a terse one-word summary denial and a reasoned decision on the merits of a motion but also between a twenty-year prison sentence and a different outcome altogether. And so, in the following sections, we consider procedural reforms that can help mitigate these pernicious effects.

Externality regulation often takes one of (at least) two forms: first, policymakers might directly address the underlying behavior giving rise to the consequences of concern; or, second, policymakers might impose rules—taxes, say—that require the actors causing these negative effects to internalize the costs of those effects.[214] Consider, for example, a chemical factory using a production process that creates a toxic byproduct. Policymakers may respond in a few ways. First, they might decide to directly ban the dangerous process, thus forcing the factory owners to use a different process or enter a different business. Alternatively, they might decide to tax the toxic byproduct to create a fund for mitigation and clean-up measures, letting the factory owners decide whether the cost of the tax is worth the pecuniary benefits of the toxic process.