Sex-Defining Laws and Equal Protection

Many equal protection challenges to the recent onslaught of anti-transgender legislation ask courts to determine the constitutional limits of the state’s ability to define sex. In these cases, transgender plaintiffs argue that the state violates constitutional guarantees of sex equality when its definition of sex coercively assigns them to a sex category against their will. The canon of constitutional sex discrimination, however, does not directly raise or answer definitional questions of sex. The canonical cases addressed the state’s ability to treat men differently from women—not the state’s ability to define “men” and “women.” This difference between the canonical cases and what this Article calls “sex-defining” cases does not necessitate any monumental shifts in equal protection doctrine, but it does require courts to tweak their intermediate scrutiny analyses. The canonical cases tested the fit between the state’s important interests and the law’s differential treatment of men and women, but sex-defining cases require courts to test the fit between the state’s important interests and the law’s definition of sex. In most sex-defining cases, however, courts ignore this essential question. This failure has produced pro-trans decisions that are correct in their conclusions but flawed in their reasoning. As the likelihood of a grant of certiorari in one of these sex-defining cases rises, so do the stakes of these mistakes.

This Article uses the pro-trans bathroom cases to illustrate what can go wrong when courts fail to examine the connection between the state’s definition of sex and its proffered justifications for the law. These decisions deem trans-exclusionary bathroom rules unconstitutional for reasons that have little to do with the state’s definition of sex, and instead, employ rationales that are fact-bound, narrow, and doctrinally questionable. Anti-trans courts, therefore, can and have upheld these laws with superficial and circular reasoning, without rebutting counter-analyses from pro-trans decisions. The second half of this Article is prescriptive and urges courts to adopt a contextual approach to sex when analyzing challenges to sex-defining laws. It makes clear how this approach flows directly from equal protection doctrine and how it lends itself to more doctrinally disciplined and normatively sound conclusions in sex-defining cases.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

During Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s confirmation hearing, Senator Marsha Blackburn asked her to define the word “woman.”[1] Justice Jackson declined, reminding the Senator that judges do not define words outside the context of a specific case or controversy. “What I do,” Jackson explained, “is I address disputes. If there’s a dispute about a definition, people make arguments, and I look at the law, and I decide.”[2] Justice Jackson might have to do exactly that regarding the definition of sex in the near future. Constitutional challenges to laws that define sex have produced a large and conflicting body of case law, making a grant of certiorari in one of these cases both probable and imminent.[3]

The laws at the center of these challenges, what I call “sex-defining” laws,[4] are a product of state legislatures and school boards, among other legal actors, codifying what they understand to be the true meaning of sex. For the most part, these laws define sex based on some combination of sex assigned at birth (SAAB), genitalia, chromosomes, and reproductive anatomy. Under these laws, people assigned male at birth (AMAB), who have penises, testes, and XY chromosomes are male, while people assigned female at birth (AFAB), who have vaginas, ovaries, uteruses, and XX chromosomes are female. These definitions are deployed to determine if someone is male (M) or female (F)[5] for bathroom access, participation on single-sex sports teams, and eligibility for sex marker changes, among other things.[6] Since these laws do not include gender identity[7] in their definitions of sex, they often force transgender people into a sex category against their will and counter to their sense of self. For example, under a law that defines sex as SAAB for sex-segregated sports teams, a transgender man (someone whose gender identity does not align with the law’s SAAB-based definition of sex)[8] would be categorized as F and banned from the men’s sports team. Indeed, excluding transgender people from spaces that align with their gender identity is widely understood to be a primary motivation behind and function of these rules.[9]

Transgender plaintiffs have brought equal protection challenges to these sex-defining laws, arguing that they misclassify the plaintiffs’ sex and, in turn, constitute sex discrimination. These cases ask judges to determine the constitutional limits of the state’s ability to define sex. But the canon of constitutional sex discrimination does not explicitly tell them how to answer this question.[10] The canonical cases[11] (including, for example, United States v. Virginia (VMI),[12] Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan,[13] and Craig v. Boren[14]) addressed whether the state could treat men and women differently to achieve its goals. If the differential treatment was based on an insufficiently important state interest or did not advance the state’s interest, the Court struck down the law.[15]

Equal protection challenges to sex-defining laws, on the other hand, are not about the state’s ability to make distinctions between men and women; they are about the way the state has sorted people into M and F categories.[16] For instance, the plaintiffs in the bathroom cases are not challenging the state’s ability to have sex-segregated bathrooms, i.e., its ability to require men to use the men’s bathroom and women to use the women’s bathrooms.[17] Instead, they are arguing that the bathroom rules’ definitions of sex, as applied to them, miscategorize their sex and force them into a sex category that is both incorrect as a matter of fact and discriminatory as a matter of law.

The differences between the canonical cases and sex-defining cases do not require courts to depart from the fundamental principles of constitutional sex discrimination: both types of cases trigger intermediate scrutiny because they treat people differently based on sex.[18] But sex-defining cases do require courts to apply intermediate scrutiny differently. Under intermediate scrutiny, the state must show that (1) the law at issue is supported by important interests (the “important purpose” prong), and (2) the means employed substantially relate to those interests (the “ends-means” prong).[19] In the canonical cases, courts applied this test to determine whether treating men and women differently substantially related to an important governmental interest.[20] In sex-defining cases, however, the question is whether the definition of sex substantially relates to an important governmental interest.[21] In other words, the ends-means prong in the canonical cases examined the fit between the differential treatment of men and women[22] and the state’s interests, whereas the ends-means prong in sex-defining cases tests the fit between the definition of sex and the state’s interests.

A handful of courts have acknowledged this difference between the canonical and sex-defining cases,[23] and a subset of those courts have modified their ends-means analysis accordingly.[24] But many have not.[25] In turn, many cases have ultimately come to the right conclusion (that these laws violate equal protection) but have struggled to tackle head-on the crucial question of whether the state’s definition of sex advances the state’s proffered interests. Instead, these pro-trans decisions[26] have deemed these laws unconstitutional for reasons that have little to do with the state’s definition of sex. Not only has avoiding this central issue made parts of their reasoning narrow and doctrinally questionable, it has also left intact the state’s faulty arguments and the flawed assumptions underlying those arguments.

This Article uses the pro-trans bathroom cases[27] to illustrate what can go wrong when courts’ analyses ignore the fit between the state’s chosen definition of sex and the state’s proffered justifications for the law. These courts conclude that excluding the transgender boy plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom is unconstitutional, but they do not answer one of the most important questions: why the state’s definition of sex for bathrooms (in these cases, SAAB/genitals), when applied to the plaintiffs,[28] fail to advance the state’s purported privacy interests behind the bathroom rules. Instead, they rely on facts that are unrelated to the reason for the plaintiff’s exclusion from the bathroom, like idiosyncratic aspects of the bathroom policies and case-specific facts about the plaintiffs’ bathroom conduct. These facts, though not always irrelevant to an equal protection analysis, are not dispositive. Thus, these pro-trans decisions are easily distinguishable in future bathroom cases that have different facts but the exact same trans-exclusionary bathroom rule.

Not only are these decisions unhelpful in cases with slightly different facts, they also miss the opportunity to undermine the state’s central argument. According to the state, “biological sex” (i.e., SAAB/genitals) is the only way to determine sex for bathrooms, if not for all purposes. Thus, under the state’s theory, a transgender boy is F because he was AFAB or has a vagina. Therefore, the state argues, allowing him access to the boys’ bathroom would mean it could no longer have sexed bathrooms. As Part III of this Article shows, the argument that a decision for the plaintiffs spells the end of sex-segregated bathrooms and the assumption upon which it is based (that SAAB/genitals always determine sex) are both flawed.[29] But the pro-trans bathroom cases failed to expose these flaws. And because they didn’t, other courts have readily adopted these same assumptions, regurgitated the state’s arguments, and transformed these arguments into law, without needing to contend with counter-analyses from the pro-trans decisions.

These holes in pro-trans decisions are becoming increasingly concerning for transgender litigants and the fight for LGBT equality in general. Initially, most of these courts ruled in favor of the transgender plaintiffs.[30] But more recently this winning streak has been slowing. For example, in its final act of 2022, the en banc Eleventh Circuit reversed its previous panel decision in Adams v. School Board of St. Johns County and held that a school board’s rule requiring students to use the bathroom matching their “biological sex” passed constitutional muster.[31] This decision did not come as a surprise,[32] but it did create a circuit split.[33] With a showdown at the Supreme Court over these bathroom rules brewing and with anti-trans sex-defining laws continuing to proliferate, transgender plaintiffs need, but do not necessarily have, strong and well-reasoned precedent upon which to challenge these laws.

This Article takes existing principles of equal protection doctrine and explains how pro-trans advocates and courts can apply them in ways that produce more doctrinally sound decisions. Put simply, it argues that in challenges to sex-defining laws, the relevant means by which the state is achieving its goal is the definition of sex, not the differential treatment of men and women. Thus, to determine whether that definition substantially relates to the relevant state interest, courts need to (1) specify how the state is defining and deploying sex (i.e., identify the means), and (2) determine whether that definition of sex substantially relates to the state’s important interest (i.e., conduct the ends-means analysis).

Courts can more easily answer these questions by incorporating what scholars have called a “context-informed” or “contextual” approach to sex in their equal protection analyses.[34] A contextual approach seeks to align the law’s definition of sex with the goal or function of the particular law at issue. Whether a law can or should define sex based on gender identity, SAAB, genitals, chromosomes, or something else depends on why that particular law is using sex in the first place. In other words, a contextual approach should guide courts’ end-means prong analyses in sex-defining cases.

This Article focuses on the cases involving sex-defining laws for bathroom access, as opposed to other sex-defining laws, for three reasons. First, there is a current circuit split on the constitutionality of these laws.[35] Second, sex-defining laws for bathrooms began proliferating many years ago[36] and have therefore produced more case law than other sex-defining laws.[37] Three federal courts of appeals have addressed equal protection challenges to bathroom rules: the Fourth Circuit,[38] the Eleventh Circuit,[39] and the Seventh Circuit.[40] Third, these opinions make similar doctrinal missteps, which means that these mistakes are not one-off errors and instead reflect a broader pattern of misunderstanding.

This Article makes several contributions to the literature. First, it tracks how equal protection challenges to sex-defining laws differ from the canon, causing many courts to confuse the constitutional analysis.[41] It also unearths the doctrinal and normative problems with the pro-trans bathroom cases and makes clear the stakes of these mistakes.[42]

Moreover, this Article contributes to the scholarship on contextual identity in law. Other projects offer contextual approaches to race,[43] sex,[44] age,[45] disability,[46] and sexual orientation[47] as remedies to existing problems in law, and others highlight how law has used context-dependent definitions of identity to maintain sexual[48] and racial[49] hierarchies. This Article builds on this work and applies a contextual understanding of sex to equal protection challenges to sex-defining laws. In doing so, it both exposes and helps remedy the current flaws in some pro-trans decisions. It also applies a contextual lens to the case law upon which anti-trans courts and litigants rely to reveal how these legal actors have mischaracterized these cases and to show why their legal arguments lack a doctrinal foundation. Finally, this Article develops the language to capture what some courts are already doing,[50] and provides a framework for courts to distinguish challenges to the state’s ability to draw distinctions between men and women (cases like the canon) and cases that challenge the state’s ability to define M and F.

Two points about this Article’s scope. First, the plaintiffs in the bathroom cases brought claims under the Equal Protection Clause and Title IX, but this Article focuses only on equal protection claims. Title IX is limited to educational contexts, but the legal battles over transgender rights are far broader. Access to bathrooms, access to healthcare, eligibility for single-sex sports teams, and requirements for changing sex markers on identity documents, for example, do not always implicate Title IX but do tend to implicate the Equal Protection Clause.[51] Therefore, I limit my analysis to equal protection because of its broader applicability. Second, this Article does not directly challenge the constitutionality of sexed bathrooms.[52] This question is not presented in these cases,[53] and neither the plaintiffs nor the courts seem to think that sexed bathrooms raise constitutional problems.[54] Instead, this Article maps a path for courts to conclude that these bathroom rules’ SAAB/genital-based definitions of sex do not survive intermediate scrutiny without directly undermining the constitutionality of sexed bathrooms.

This Article proceeds as follows. Part I maps the differences between the canonical cases and sex-defining cases. It shows how these differences require courts to tweak their intermediate scrutiny analyses but do not justify a departure from the core principles established in the canon. Part II discusses the bathroom cases. First, it provides a close reading of the pro-trans decisions and argues that their failure to address the critical question of fit between the state’s definition of sex and the state’s privacy goals weakens their precedential value and limits their applicability. It then turns to the en banc decision in Adams and argues that the gaps in the pro-trans decisions’ reasoning allowed this anti-trans court to craft a deeply flawed opinion without needing to confront or rebut relevant counter-analyses. Part III provides a path forward. It explains the concept of contextual sex and how it both flows from and maps directly onto existing equal protection doctrine. Then, it spells out how this approach can remedy the flaws in the pro-trans bathroom cases discussed in Part II before applying a contextual approach to the bathroom cases. Part IV is a brief conclusion.

I.The Canon of Sex Discrimination and Sex-Defining Cases

This Part first traces how equal protection challenges to sex-defining laws differ from the types of constitutional sex discrimination challenges courts are used to and describes the framing and analytical shifts those differences require. Then, it explains why courts should not throw the baby out with the bath water—that is, even though sex-defining cases require analytical tweaks, they implicate the core principles of constitutional sex discrimination that were established in the canon.

A. The Differences Between the Canonical Cases and Sex-Defining Cases

Courts are familiar with equal protection challenges that track the canon of constitutional sex discrimination: cases like United States v. Virginia[55] and Craig v. Boren.[56] These canonical cases addressed laws that treated men and women differently, e.g., laws that denied women admission to a state university,[57] allowed women to drink alcohol at a younger age than men,[58] and gave preference to men over women as administrators of a decedent’s estate.[59] The plaintiffs were asking the Court to require sex neutrality and to strike down the M/F sex classifications in the law.[60] In these cases, the laws at issue did not explicitly define sex and the plaintiffs did not claim that the state had improperly classified them as M instead of F, or vice versa.[61]

Sex-defining cases, on the other hand, are not about the permissibility of M/F sex classifications.[62] In the bathroom cases discussed in Part II, for example, the plaintiffs repeatedly reminded the court that they were not arguing that sexed bathrooms writ large are unconstitutional. Indeed, these plaintiffs’ claims were based on the existence of sexed bathrooms: they wanted to use a sexed bathroom, not a sex-neutral one.[63] Rather, these plaintiffs challenged the way the state was implementing the sex classification. They argued that the state’s definition of sex, as applied to them, was unconstitutional sex discrimination because it misclassified their sex and forced them to use the wrong bathroom. The plaintiffs’ harms, as they articulated them, did not flow from the state treating men and women differently; they were caused by the state improperly designating them as M or F.

Compare the goals of the plaintiffs in United States v. Virginia (VMI)[64] and Grimm v. Gloucester County School Board.[65] VMI, a core pillar of the canon, addressed the state’s ability to exclude all women from Virginia Military Institute, a public military university.[66] There were no disputes as to how the university determined which applicants were women, and the parties were not arguing over the “true” sex of a particular applicant.[67] Rather, the challengers claimed that denying all women admission to the university was unconstitutional sex discrimination.[68] Grimm, on the other hand, involved a challenge to a school’s bathroom rule that assigned students to sexed bathrooms based on their SAAB/genitals. The plaintiff, a transgender boy, was not permitted to use the boys’ bathroom based on his SAAB/genitals.[69] He argued that the rule was unconstitutional, as applied to him, because it defined his sex as F and forced him to use a bathroom that did not align with his male gender identity.[70] Unlike the challengers in VMI, Grimm did not want the court to end sexed bathrooms; he wanted to be properly classified as M.

Because sex-defining cases are challenging the definition of sex, not the M/F sex classification, the equal protection analysis in each type of case is slightly different. Both apply intermediate scrutiny’s familiar two-step framework: (1) the important purpose prong—whether the law is supported by an important governmental interest; and (2) the ends-means prong—whether the means employed substantially relate to that interest.[71] Sex-defining cases and the canonical cases, however, differ slightly on the ends-means prong. In canonical cases like VMI, the means was the differential treatment of men and women, and courts determined whether this differential treatment was substantially related to an important governmental interest (the ends).[72] In sex-defining cases, however, the relevant means is different; the state is achieving its goal through its definition of sex.[73] Thus, sex-defining cases require courts to determine whether the state’s definition of sex (not the differential treatment of men and women) substantially relates to an important governmental interest. To answer this question, then, courts need to (1) ascertain exactly how the state is defining sex and (2) examine whether that definition substantially relates to the state’s goal. The canonical cases did not have to ask or answer these questions, and therefore courts cannot look to the canon for guidance on this part of the equal protection analysis.[74]

Another difference between the canon and challenges to sex-defining laws is that the former are mostly facial challenges whereas the latter are mostly as-applied challenges.[75] In VMI, for example, the claim was that VMI’s policy of excluding women was unconstitutional on its face, as applied to everyone, not that VMI’s exclusion of particular women was unconstitutional (which would be an as-applied challenge).[76] Challenges to sex-defining laws, for the most part, are as-applied.[77] These plaintiffs are not arguing that the state’s definition of sex is unconstitutional writ large, but rather that the definition is unconstitutional only when applied to the transgender plaintiffs themselves. In Grimm, for instance, the plaintiff did not challenge the bathroom rule’s definition of sex when applied to cisgender students; his claim was limited to the bathroom rule’s definition of sex when applied to him.[78]

Sex-defining cases, therefore, depart from the canon in two respects. First, the plaintiffs are challenging the definition of sex, not the M/F sex classification, and second, they are doing so on an as-applied basis rather than a facial one.[79] However, as discussed further in Part II, some courts have not sufficiently shifted their analyses to account for these differences. [80] Sometimes, these courts do not even acknowledge any differences between sex-defining cases and the canon. Instead, they treat these cases as if they were challenging the M/F sex classification rather than the definition of sex.[81]

B. The Overlap Between the Canonical Cases and Sex-Defining Cases

Thus far, this Part has emphasized the differences between the canonical cases and sex-defining cases, but these differences should not be overstated.[82] Sex-defining laws and laws at issue in the canon implicate the same core equal protection principles and trigger intermediate scrutiny for the same essential reasons.[83] The canonical cases applied intermediate scrutiny to ensure that the state was not improperly restricting people’s ability to live their lives based on their sex: a label imposed upon them at birth and based on the appearance of their genitals.[84] Regardless of whether someone accepts the label assigned at birth (like the women seeking admission to VMI) or not (like the transgender plaintiffs in the bathroom cases), the label itself is something they do not have control over and something that is rarely relevant to their ability to “contribute to society.”[85] The immutable and (usually) irrelevant nature of assigned sex categories, in addition to the state’s long history of using sex as a pretext for unlawful discrimination, are the reasons why courts closely interrogate laws that deny people opportunities or harm them in other ways because of their sex. Courts need to ensure that such sex-based harm is justified.[86]

These rationales apply to sex-defining cases in the same way they did in the canonical cases. In VMI, for example, VMI’s exclusion of women triggered intermediate scrutiny because the state was limiting women’s educational opportunities and restricting their ability to control their lives, and the only reason VMI was doing so was because of their sex.[87] Heightened scrutiny applies in sex-defining cases for the same reason. These laws harm people, deny them the ability to direct the course of their lives, and exclude them from spaces and opportunities to which they seek access because of something they cannot change: their SAAB.[88]

These throughlines in both types of cases become apparent if we reframe VMI as a sex-defining case.[89] Suppose VMI limited admission to people AMAB (as opposed to the undefined category of “men”).[90] Then suppose someone AFAB challenged this rule under equal protection on an as-applied basis, just like the plaintiffs in sex-defining cases.[91] The plaintiff argued that because they thrived in the type of “adversative” educational environment VMI provides, admitting them would enhance, rather than detract from, the school’s goal of producing “citizen-soldiers.”[92] In this reformulated version of the case, the Court’s justification for applying intermediate scrutiny remains the same: VMI denied the plaintiff a unique educational experience and it did so based exclusively on their SAAB.[93] The Court’s intermediate scrutiny analysis does not change in any fundamental way either. VMI’s justification for excluding the plaintiff would still be based on overbroad and impermissible assumptions about people AFAB: that they are not amenable to VMI’s “adversative method of training” and admitting them to VMI “would downgrade VMI’s stature, destroy the adversative system and, with it, even the school.”[94]

The aspects of the Court’s analysis that would change are those already discussed in this Part. First, the Court’s ends-means analysis would examine the fit between VMI’s SAAB-based admissions policy and the state’s justifications for the policy. And second, the Court’s inquiry would be limited to this one plaintiff, not everyone AFAB.

In sum, laws that treat men and women differently (VMI) and laws that define M and F (Grimm) both trigger heightened scrutiny because they treat people unequally based on sex: either because they are women (VMI) or because they are AFAB (Grimm).

II. The Bathroom Cases

This Part discusses the implications of courts’ failure to shift their equal protection analysis in sex-defining cases, using the bathroom cases as an example. First, it provides background on three cases addressing challenges to sex-defining bathroom rules. Specifically, it discusses the facts, the details of the bathroom policies themselves, the plaintiffs’ equal protection arguments, and the state’s counter-arguments. Then it turns to the three decisions that ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. It argues that they provide unstable foundations for future sex-defining challenges because their reasoning does not address the core issues presented in these cases and, in turn, fails to rebut the heart of the state’s arguments. Subsection B turns to the en banc Adams decision—the only court of appeals bathroom decision that ruled against the transgender plaintiff. It shows how the pro-trans decisions’ failure to undermine the schools’ flawed arguments made it easy for the en banc Adams court to adopt them and rule in favor of the schools without needing to contend with relevant counter-analyses from the pro-trans decisions.

A. The Pro-Trans Cases: The Panel Decisions in Adams, Grimm, and Whitaker

The three courts of appeals that have decided equal protection challenges to school bathroom rules are the Fourth Circuit (Grimm v. Gloucester County School Board),[95] the Eleventh Circuit (Adams v. School Board of St. Johns County),[96] and the Seventh Circuit (Whitaker ex rel. Whitaker v. Kenosha Unified School District).[97] All three cases share the same basic facts. The plaintiffs were all transgender boys[98] who began using the boys’ bathroom at school.[99] Their respective school boards subsequently either passed a new rule or began enforcing a pre-existing, unwritten rule that prohibited these plaintiffs from using the boys’ bathroom.[100] These bathroom rules assign students to the bathroom that corresponds with their “biological sex.”[101] The policies do not define “biological sex,” and, during the litigation, the schools’ attorneys resisted defining the terms with precision.[102] But a close examination of the schools’ briefs and oral arguments reveals that “biological sex” refers to SAAB or genitals.[103] In other words, the policies bar these plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom because they were AFAB or have vaginas.[104] To determine students’ “biological sex,” the policies look to the sex marker on the students’ identity documents at the time they enrolled.[105]

The plaintiffs challenged the bathroom rules under equal protection and argued that the bathroom policies were unconstitutional because they misclassified the plaintiffs’ sex as F and forced them to use a bathroom inconsistent with their true sex, M.[106] They did not argue that the SAAB/genital definition of sex was unconstitutional on its face. Nor did they object to the schools’ definition of sex when applied to cisgender students,[107] only when applied to transgender students.[108] In other words, how the schools assign cisgender students to bathrooms was irrelevant in these cases.

The schools, for their part, put forth two related, but slightly distinct, justifications behind their policies and argued that both were sufficiently important to survive intermediate scrutiny: (1) protecting their students’ interests in bodily privacy from the “opposite sex”[109] in the bathroom[110] and (2) ensuring their students had privacy in using the bathroom away from the “opposite sex.”[111]

The schools did not expound on the first interest (“bodily privacy from the opposite sex”) with great specificity, but they seemed to be referring to privacy interests implicated by the actual or potential exposure to the “nude or partially nude body, genitalia, and other private parts . . . of the opposite biological sex” in the bathroom.[112] According to the schools, allowing these plaintiffs to use the boys’ bathroom undercut this interest because they are not “biological boy[s]” (based on their SAAB/genitals) and allowing “biological girls” to use the boys’ bathroom put cisgender boys at risk of exposing their bodies to the opposite sex.[113] Under this logic, excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom is not only substantially related to this interest, but is its mirror image since avoiding any risk of opposite sex bodily exposure requires banning “biological girls” from the boys’ bathroom.[114]

The schools’ other justification for the bathroom rule—students’ privacy interest in using the bathroom away from the opposite sex––is essentially a justification for maintaining sexed bathrooms writ large. That’s because the schools think these challenges threaten their ability to maintain sex-segregated bathrooms; that is, they understand these cases to be about the schools’ ability to segregate bathrooms by “biological sex.”[115] Under the schools’ theory, allowing these transgender plaintiffs to use the boys’ bathroom would spell the end of sexed bathrooms because it would allow a “biological girl” to use the boys’ bathroom.[116] If a “girl” can use the boys’ bathroom, under the schools’ logic, there would no longer be a basis upon which to separate bathrooms based on sex.

The fundamental disagreement between the schools and the plaintiffs, therefore, revolved around how the schools defined the plaintiffs’ sex for bathrooms. For the schools, the plaintiffs are “girls” because their sex is dictated by their SAAB/genitals, and SAAB/genitals are the only way to determine someone’s sex, not only for the purposes of bathrooms but seemingly for all purposes.[117] The plaintiffs’ gender identity, appearance, and secondary sex characteristics are irrelevant to their sex, according to the schools.[118] For the plaintiffs, SAAB/genitals are not the only way to define sex, and, for transgender students like them, they are also the wrong way to define sex. The plaintiffs marshaled expert testimony and detailed narratives of their medical and social transitions to prove that their gender identity, and therefore their true sex, is M.[119]

All three pro-trans decisions applied intermediate scrutiny to the plaintiffs’ equal protection claims and held that the bathroom rules, as applied to the plaintiffs, were unconstitutional.[120] They also all agreed with the plaintiffs that these cases were not about the constitutionality of sexed bathroom writ large and instead were about the schools’ ability to exclude the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom.[121] In this sense, they understood that these cases were different from canonical cases.[122] However, they did not set up or analyze these claims in ways that cut to the heart of these cases.

As explained in Part I, the questions presented in sex-defining cases, such as these bathroom cases, differ from the questions in canonical cases.[123] In sex-defining cases, the relevant means by which the state is achieving its goal is the state’s precise definition of sex.[124] Therefore, in the bathroom cases, the questions presented under intermediate scrutiny are (1) whether the schools’ interests behind the bathroom rule (students’ privacy interests in both shielding their bodies from the opposite sex in the bathroom and in using the bathroom away from the opposite sex) are sufficiently important and (2) whether the schools’ definition of sex, as applied to the plaintiffs, substantially relates to those interests. But none of these decisions asked or answered these precise questions.[125] Instead, they relied on rationales that were based on idiosyncratic and easily fixable aspects of the bathroom policies or case-specific facts about the plaintiffs’ bathroom conduct that might not be present in other cases. While each court framed its analysis slightly differently, there are two flawed lines of reasoning that run through the three decisions: (1) the schools’ interests in bodily privacy were not advanced by excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom because the plaintiffs (or any other transgender student) did not violate anyone’s bodily privacy in the bathroom; and (2) using the sex marker at the time of enrollment to determine bathroom access was arbitrary because it made transgender students’ access to the bathroom contingent on whether they changed their sex marker pre- or post-enrollment. The following discussion addresses these two rationales in turn and explains their doctrinal and normative flaws.

1. Courts’ Rationale 1: Improper Reliance on the Lack of Bodily Privacy Infringements

All three decisions shot down the schools’ privacy justifications for their bathroom policies with the same basic rationale. The factual records in all three cases were devoid of evidence that the plaintiffs violated other students’ bodily privacy in the bathroom.[126] Based on this lack of evidence, these courts reasoned that the bathroom policies’ privacy justifications were either (1) merely conjectural and failed the important purpose prong of intermediate scrutiny, or (2) not advanced by excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom and failed the ends-means prong.[127] In other words, because these transgender students were not violating cisgender boys’ bodily privacy by “sneaking a peek” at cisgender boys’ genitals or exposed bodies while using the bathroom, the schools’ privacy concerns were not sufficiently important to survive scrutiny and excluding these plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom did not affect student privacy. Sometimes, these courts bolstered this argument by noting the lack of evidence that any transgender student violated other students’ privacy in the bathroom. For instance, the Grimm majority employed this reasoning in its ends-means analysis, writing:

The Board does not present any evidence that a transgender student, let alone Grimm, is likely to be a peeping tom, rather than minding their own business like any other student. Put another way, the record demonstrates that the bodily privacy of cisgender boys using the boy’s restrooms did not increase when Grimm was banned from those restrooms. Therefore, the Board’s policy was not substantially related to its purported goal.[128]

And the Adams panel opinion—albeit in dicta, responding to the dissent—invoked this same logic, stating that “the School District has never shown how its policy furthers [a privacy interest], as this record nowhere indicates that there has ever been any kind of ‘exposure’ . . . [And] nothing in the record suggests Mr. Adams or any other transgender student ever threatened another student’s privacy.”[129] The Whitaker decision also relied on the absence of complaints about the plaintiff using the boys’ bathroom, highlighting “the practical reality of how [the plaintiff], as a transgender boy, uses the bathroom: by entering a stall and closing the door.”[130] Therefore, because the plaintiff did not do anything in the bathroom that might put other boys’ privacy at risk, the school had no privacy-related reason to exclude him.

The following discussion argues that this line of reasoning is problematic for at least three reasons: (1) it is unresponsive to the schools’ privacy-based justifications for their bathroom rule and therefore leaves those justifications fully intact for future anti-trans courts and litigants to deploy; (2) it misidentifies the proper ends and means and creates a doctrinal flaw in these decisions; and (3) it leaves several important questions unanswered, leaving room for anti-trans courts to answer them in troubling ways.

a. This Rationale is Unresponsive to the Schools’ Justifications

This “no evidence of bodily privacy violations” rationale is not entirely responsive to the schools’ justifications behind their bathroom rules: it does not address the “privacy in using the bathroom away from the opposite sex” justification at all and it is only partially responsive to the “bodily privacy from the opposite sex” justification.

i. Schools’ First Justification: Privacy in Using the Bathroom Away from the Opposite Sex

The schools’ “privacy in using the bathroom away from the opposite sex” justification is unrelated to actual or potential bodily exposure. The schools argued that this interest was implicated when the plaintiffs merely entered the bathroom because they are girls.[131] Under the schools’ logic, therefore, the lack of bodily privacy violations is irrelevant: the plaintiffs invade other boys’ privacy by their mere presence in the boys’ bathroom.

The non-responsiveness of this “no evidence of bodily privacy violations” line of reasoning would not be a problem if these decisions explained why this privacy interest was either not sufficiently important or why excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom failed to advance this interest. But they did not.[132] Indeed, these courts agreed (or did not contest) that the schools have an important state interest in promoting student privacy interests through sex-segregated bathrooms.[133] This isn’t surprising: the plaintiffs agreed with this claim too.[134] The point of disagreement between the schools and the plaintiffs was whether excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom based on their SAAB/genitals advances this interest. By ruling in favor of the plaintiffs, these courts implicitly sided with the plaintiffs on this question.[135] However, they provided only conclusory rationales rather than explaining why excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom did not advance the schools’ opposite-sex privacy interest. The closest the courts came to providing a substantive answer on this point was merely stating that the plaintiffs are boys. Because the plaintiffs are boys, these courts reasoned, they are the same sex as cisgender boys, not a different sex.

For instance, the Adams court explained that its decision “‘will not integrate the restrooms between the sexes,’ because there is ‘no evidence to suggest [Adams’s] identity as a boy is any less consistent, persistent and insistent than any other boy.’”[136] But the court did not explain why gender identity (as opposed to SAAB/genitals) was dispositive to Adams’s sex for bathroom purposes.[137] Instead, the court relied on the fact that a state agency allowed him to change the sex marker on his birth certificate to M, explaining “we cannot simply ignore the legal definition of sex the state has already provided us, as reflected in the official documentation of Mr. Adams’s sex as male on his driver’s license and birth certificate.”[138] The Grimm court did the same thing. It rebutted the school’s claim that Grimm’s “biological sex” made him a girl for bathroom purposes by pointing to all the ways in which Grimm was just like cisgender boys: his gender identity is “consistently, persistently, and insistently”[139] male, he “wear[s] boys’ clothing;”[140] and holds himself out to his school community as a boy.[141]

By declaring that the plaintiffs’ gender identity or their identity documents dictated their sex for bathroom purposes, without explaining why these indicators were relevant to the schools’ privacy interests, the courts engaged in the same problematic reasoning as the schools.[142] Both offered different definitions of sex and concluded that their definition should dictate the plaintiffs’ sex for bathroom purposes. But they did not explain why their definition substantially related to the schools’ interests. The schools and the courts were talking past each other, both claiming that particular traits were the relevant traits to determine sex for bathrooms, but without explaining why.

Thus, neither this explanation (“the plaintiffs are boys”) nor the “no evidence of bodily privacy violations” rationale responded to, or undercut, the schools’ claim that excluding transgender boys from the boys’ bathroom was necessary to achieve privacy from the opposite sex. Nor did these courts provide a substantive challenge to the schools’ assumption that the plaintiffs are girls based on their SAAB/genitals. Therefore, even though the schools ultimately lost these cases, their argument and its underlying assumption went unrebutted.

ii. Schools’ First Justification: Privacy in Using the Bathroom Away from the Opposite Sex

These decisions’ “lack of bodily privacy violations” rationale is only slightly more responsive to the schools’ other purported interest behind the bathroom rule: bodily privacy from the opposite sex. These courts are right that the absence of bodily privacy violations indicates that the schools’ concerns about bodily privacy are conjectural.[143] But ensuring bodily privacy in the bathroom overall is not a complete or proper articulation of the schools’ stated interest. Indeed, it would have been difficult for the schools to argue that they were concerned with bodily privacy in the bathroom. The schools facilitate, or at least do nothing to prevent, same-sex bodily exposure. Cisgender students are exposed to each other’s bodies when they “change in the bathrooms” and “use undivided urinals,” but the schools expressed no concern about this type of bodily exposure. [144] Cisgender students’ bodily exposure was not just something the schools conceded was happening under their watch; they used the fact of same-sex cisgender bodily exposure as a reason why transgender students should not be able to use the bathroom.[145]

The schools’ interest is bodily privacy from the opposite sex in the bathroom, not bodily privacy in the bathrooms.[146] According to the schools, the plaintiffs are girls because they were AFAB and have vaginas; therefore, their mere presence in the boys’ bathroom creates a risk of opposite-sex bodily exposure.[147] Even if the plaintiffs behave perfectly in the bathroom, eventually they may inadvertently expose their bodies or view a cisgender boy’s exposed body. For the schools, it is only a matter of time before their concerns are actualized.[148] Thus, these courts’ reliance on the plaintiffs’ good bathroom behavior does not fully address the schools’ “bodily privacy from the opposite-sex” justification. Not dismantling this argument leaves it mostly intact for anti-trans courts and litigants to invoke in future cases.

b. This Rationale Confuses the Ends-Means Analysis

In addition to being unresponsive to the schools’ arguments, this line of reasoning is also doctrinally flawed because it confuses the ends-means analysis of intermediate scrutiny. It treats the schools’ end as bodily privacy in the bathroom and the means as banning the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom. That is, because banning the plaintiffs did not affect bodily privacy, the means did not substantially relate to the ends.[149] But these are not the relevant ends or the means: the schools’ end is preventing opposite sex bodily exposure, not preventing bodily exposure in general. And the means is keeping a “biological girl” out of the boys’ bathroom.[150] In other words, these decisions analyzed the fit between excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom and bodily privacy instead of the fit between excluding the plaintiffs from the boy’s bathroom and bodily privacy from the opposite sex in the bathroom.

Anti-trans courts have already used this doctrinal flaw to discount these courts’ ultimately correct conclusions. For instance, dissenting in the panel decision in Adams, Judge Pryor wrote: “[E]vidence that Adams or other transgender students ‘harass[ed] or peeped at’ other students in the bathroom . . . would not justify a sex-based classification. If voyeurism is equally problematic whether it occurs between children of the same or different sexes, then separating bathrooms by sex would not advance any interest in combatting voyeurism.”[151] Judge Pryor’s dissent has many problems of its own, but this part of his argument is correct. Voyeurism has nothing to do with sex.[152]

c. This Rationale Leaves Critical Questions Unanswered

A third problem with this rationale is what it leaves unsaid. When these courts dismissed the schools’ interest in bodily privacy from the opposite sex by asserting that there are no bodily privacy violations, they left unanswered several important questions, which allows future courts to provide dangerous answers. First, these decisions are silent about the durability of their reasoning in cases that do have allegations of bodily privacy violations involving transgender plaintiffs.[153] Concluding that the plaintiffs’ good bathroom behavior was part of the reason the school could not ban them from the boys’ bathroom suggests that a school may be able to exclude a badly behaved transgender plaintiff to protect bodily privacy.[154] The constitutionality of the bathroom policy should not depend on a plaintiff’s good or bad bathroom behavior, but these decisions did not preclude this possibility. And their reliance on the good behavior of other transgender students, not just the plaintiffs, amplifies this risk.[155] If a single transgender student violates someone’s bodily privacy, does this mean that all transgender students’ rights are at risk? In light of this uncertainty, transgender students may need to behave better than their cisgender peers in the bathroom to ensure that their rights are secure. They may need to be more polite, shield their bodies from exposure, and ensure their gaze never wanders onto the body of another student to secure their place in the bathroom. Cisgender students are exempt from such careful self-policing.

Moreover, if a transgender plaintiff did violate a cisgender student’s bodily privacy, these courts’ objection to the conjectural nature of the schools’ privacy interest would disappear. The schools’ concerns about bodily privacy would no longer be hypothetical. But would their concerns about bodily privacy from the opposite sex also no longer be hypothetical? If not, cisgender boys are sharing the bathroom with the opposite sex when transgender boys like the plaintiffs use the boys’ bathroom. What follows, then, is that transgender boys like the plaintiffs are not the same sex as cisgender boys and the state can assign them to the bathroom based on their SAAB/genitals. This hole in these courts’ reasoning, combined with their failure to rebut the schools’ claim that the plaintiffs are girls based on their SAAB/genitals, leaves a clear path for anti-trans courts and litigants to continue invoking their flawed arguments without needing to distinguish these cases. And as Part II.B shows, the Adams en banc court did exactly that.[156]

Another question this line of reasoning raises but does not answer is whether the plaintiffs’ good bathroom behavior was related to their sex. By relying on the absence of privacy violations committed by the plaintiffs, these courts suggested (or at least did not rebut) some association between good behavior in the bathroom and transgender identity. Of course, these transgender students’ good behavior in the bathroom had nothing to do with their “sex” and therefore could not have been the basis for their ability to use the boys’ bathroom.[157] But failing to make this point explicit runs the risk of implicitly tying bathroom conduct to “sex.” It is also the mirror image of a common anti-trans argument that transgender people will behave like predators in the bathroom because of their sex or transgender status.[158] When these courts linked good bathroom behavior to transgender identity, they might have legitimized the foundations of this anti-trans argument. Assuming that someone’s behavior in the bathroom is related to their sex, generally, or their transgender identity, specifically, is an impermissible sex stereotype.[159]

2. Courts’ Rationale 2: Overreliance on the Policy’s Use of Sex Markers

A second common rationale these decisions employed relates to how the bathroom rules determine “biological sex.” These rules assign students to bathrooms based on their “biological sex.” “Biological sex” is determined by the sex marker on students’ birth certificates at the time they enrolled in the school.[160] Students’ sex markers at the time of their enrollment are not always perfect proxies for “biological sex” (SAAB/genitals), particularly when it comes to transgender students. That’s because in many states, people under eighteen can change the sex markers on their birth certificates and other identity documents without modifying their “biological sex.”[161] Therefore, if a transgender boy student changed the sex marker on his birth certificate from F to M before enrolling in the school, his “biological sex” at the time of enrollment would be M and he could use the boys’ bathroom. But if he changed his sex marker to M after enrolling, his “biological sex” would remain F and he could not use the boys’ bathroom. [162] Thus, these policies are not 100 percent effective in keeping people AFAB or with vaginas out of the boys’ bathroom because transgender boys who changed their sex marker prior to enrolling can use the boys’ bathroom.

All three decisions took issue with this aspect of the bathroom policies. They reasoned that because transgender boys’ ability to use the boys’ bathroom is based on whether they changed their sex marker pre- or post-enrollment, the policies were either arbitrary or failed to advance the schools’ goal of keeping “biological girls” out of the boys’ bathroom. Of the three panel opinions, Adams relied most heavily on this line of reasoning.[163] The plaintiff, Andrew Adams, enrolled before changing his sex marker to M, but if he had enrolled after changing his sex marker to M, he would not have been barred from the boys’ bathroom.[164] The court held that this differential treatment based on the time of enrollment made the rule unconstitutionally arbitrary because it “target[ed] some transgender students for bathroom restrictions but not others.”[165] According to the court, the policy was both arbitrary and failed to successfully exclude all “biological girls” from the boys’ bathroom because students who were AFAB or had a vagina could use the boys’ bathroom if they enrolled after a sex-marker change.[166] Like the Adams court, Grimm[167] and Whitaker[168] also deemed the policies ineffective or arbitrary based on the policies’ differential treatment of transgender students.

While these decisions are right that sex markers are not perfect proxies for “biological sex,” this rationale is (1) doctrinally flawed, and (2) suggests that fixing this proxy would render the bathroom rule constitutional. First, the relevant question of fit is not between the sex markers on students’ identity documents and the students’ “biological sex.” The relevant fit is between the goals of the bathroom rules and the means the rules employ to achieve those goals. The goals of these bathroom rules relate to privacy away from another sex in the bathroom—not accurately determining “biological sex.” And the means the rules use to achieve those ends is defining sex based on SAAB/genitals—not using sex markers on documents. Thus, the fit courts should have examined was the one between the schools’ interest in privacy away from the opposite sex and the plaintiff’s SAAB/genitals.[169]

This doctrinal misstep on the ends-means analysis opens these pro-trans courts to doctrinal critiques from anti-trans courts who have used this flaw to their advantage. The anti-trans Adams en banc court cited this aspect of the Adams panel’s decision as one reason to reverse. Specifically, it stated that the panel improperly framed Adams’s claim “as a challenge to School Board’s enrollment documents policy—i.e., the means by which the School Board determines biological sex upon a student’s entrance into the School District,” rather than addressing Adams’s “challenge to the School Board’s bathroom policy—the policy separating the male and female bathrooms by biological sex.”[170]

Beyond the doctrinal problem, another flaw with these courts’ objection to the imperfect proxy between “biological sex” and sex markers is that the schools can easily fix this problem by using students’ original birth certificates to determine SAAB/genitals instead of amended birth certificates. While not necessarily perfect indicators of “biological sex,” original birth certificates are better proxies for SAAB/genitals than amended birth certificates.[171] Using original birth certificates would solve one of these opinions’ main objections to the policies: that they are arbitrary because they treat transgender students differently depending on whether they enrolled before or after changing their sex marker.[172] Transgender plaintiffs would still be barred from the boys’ bathroom under such a bathroom policy, but would such a policy be constitutional? These decisions are silent on this point. All of sudden, with a slight change in the policy, a major piece of these opinions’ equal protection holding falls away.[173] But nothing changes for the plaintiffs and the other transgender students governed by these policies—they still can’t use the boys’ bathroom. These opinions, or at least this aspect of these pro-trans opinions, will be of little value to future plaintiffs challenging similar rules that use original birth certificates instead of amended ones. Rather, the state will be able to use this reasoning to its advantage by arguing that this constitutionally problematic aspect of the policy has been remedied and therefore the policy is constitutional.

3. Possible Explanations for These Rationales

These pro-trans decisions are ultimately correct, but they are of limited use in future sex-defining equal protection cases. They did not explain why excluding the plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom based on their SAAB/genitals failed to advance the schools’ two privacy-related justifications for their policies. Nor did they confront or rebut the foundational assumption underlying the schools’ arguments: that SAAB/genitals dictate the plaintiff’s sex for bathroom purposes. Moreover, their reasoning does not apply to cases with allegations that a transgender plaintiff violated someone’s bodily privacy in the bathroom or to cases where “biological sex” is determined using an original birth certificate rather than an amended one. Knowing with absolute certainty why these courts are making these mistakes is impossible, but I offer some explanations below.

a. The Ends-Means Analysis Differs from the Canon

Both the “no evidence of privacy infringement” rationale and the “inconsistent sex marker rationale” can be understood as ends-means errors. The “no evidence of privacy infringement” rationale treats bodily privacy as the schools’ end and excluding students who violate their peers’ bodily privacy as the means. But the schools’ end is bodily privacy from the opposite sex, not overall bodily privacy.[174] And the “inconsistent sex marker” rationale misunderstands the schools’ ends as determining “biological sex” and the means as sex markers.

One possible explanation for the courts’ mistakes stems from the fact that the sex-defining cases require a different ends-means analysis than the canon.[175] The means in sex-defining cases is the definition of sex, not the differential treatment of men and women (like in the canon).[176] So, in sex-defining cases, identifying exactly how the state is defining sex and determining whether the definition advances the state’s interests are crucial. These are new tasks for courts, and the canon does not provide courts with explicit instructions on how to answer these questions, which might have contributed to the pro-trans courts’ errors.[177]

b. Schools Obfuscating Their Definition of “Sex”

The canon’s lack of direct guidance on the ends-means prong might not be the only reason these opinions’ ends-means analyses are flawed. Because the relevant means in sex-defining cases is the definition of sex, identifying the exact definition of sex is crucial to determining the constitutionality of the rules. But the schools’ attorneys made this difficult for these courts by repeatedly obscuring their rules’ exact definition of sex.[178] The schools used terms like “biological sex” or “biological gender” to define “sex,” but did not provide additional specificity.[179] Even when pressed by courts, the schools’ attorneys resisted requests to clarify their definition of “biological sex.” In lieu of precision, they sometimes said that “biological sex” meant the sex markers on the students’ identity documents. But, as explained, sex markers are not the school’s definition of “biological sex”: sex markers are a proxy for whatever “biological sex” means. Without a specific definition of sex, the courts could not determine whether that definition of sex substantially relates to the schools’ privacy goals.

c. As-Applied Nature of the Bathroom Cases

The as-applied nature of these bathroom cases may also have something to do with these decisions’ weaknesses. Courts do not have much practice with as-applied equal protection challenges. The canonical cases were facial challenges,[180] as are most other equal protection cases.[181] Thus, the pro-trans bathroom courts might have misunderstood how the as-applied versus facial distinction affected the equal protection analysis due to their lack of familiarity with as-applied challenges in sex discrimination cases. With as-applied challenges, courts focus on the facts of the specific case and ask whether the state violated the rights of the specific plaintiffs under specific factual circumstances: for example, whether a law survives constitutional muster when applied to a particular religious group.[182] But the underlying legal test or issues presented do not change.[183] What changes are the scope of the inquiry and the remedy. The facial version of the plaintiffs’ claim in the bathroom cases would be whether assigning all students to bathrooms based on their SAAB/genitals substantially relates to the schools’ privacy interests. The as-applied version asks whether excluding the plaintiffs based on their SAAB/genitals substantially relates to the schools’ privacy interests.

These pro-trans decisions might have thought that the as-applied nature of these challenges justified their reliance on specific factual circumstances—namely, the plaintiffs’ good bathroom behavior and the bathroom rules’ use of sex markers.[184] However, the as-applied nature of these cases did not give these courts a green light to rely on any of the specific facts in the record. The specific facts upon which courts rely in as-applied challenges still must relate to the central legal question presented in these cases. But the facts upon which the pro-trans decisions relied (no bad behavior and the fact that sex markers are an imperfect proxy for SAAB/genitals) were not why the plaintiffs were excluded from the boys’ bathroom. They were excluded because they were AFAB or had vaginas.

d. Preserving a Justification for Sexed Bathrooms

Anti-trans courts and litigants equate these courts’ rulings in favor of the plaintiffs with the elimination of sexed bathrooms altogether, painting these decisions as radical departures from deeply entrenched social norms.[185] Perhaps these courts invoked these two fact-specific, tangential rationales instead of addressing the core issues in these cases because they did not know how to do so without adding fuel to these anti-trans accusations. In other words, these courts may have been unsure how to conclude that the school could not exclude these plaintiffs from the boys’ bathroom based on their SAAB/genitals in a way that preserved the school’s ability to exclude cisgender boys from the girls’ bathroom (or vice versa). If the school could not exclude transgender boys from the boys’ bathroom because they have vaginas or because they were AFAB, then why can the school exclude cisgender girls, who also were AFAB and have vaginas? Maybe these courts thought that answering the core question in these cases (whether excluding the plaintiffs based on the SAAB/genitals advances privacy) required them to answer a question they did not know how to answer (why the school could, nevertheless, continue to exclude cisgender girls from the boys’ bathroom).

If these courts were under this impression, their avoidance of the core issues in these cases makes perfect sense. But this impression is false for two reasons. First, it fails to fully appreciate how the as-applied nature of these challenges limits the questions these courts must answer. These challenges have nothing to do with how the schools assign cisgender students to bathrooms. These plaintiffs have no objection to the schools’ definition of sex when applied to cisgender students, only when applied to transgender students.[186] Courts can conclude that the school cannot ban transgender boys from the boys’ bathroom without saying anything about cisgender students. Second, a decision that the school cannot define sex based on SAAB/genitals, as applied to transgender students or all students, does not mean that the school cannot have sexed bathrooms. SAAB/genitals are not the only way to determine sex for bathrooms. Part III explains how courts can do this, but for now, the point is that pro-trans courts’ errors might stem from wanting to avoid accusations that their decisions ban sex-segregated bathrooms writ large.[187]

B. The En Banc Decision in Adams

Regardless of why these courts did not directly answer the questions at the heart of these cases, their failure to do so made it easy for the Adams en banc court to reverse the panel’s decision and rule in favor of the school.[188] Neither the Adams panel nor the other two cases directly undermined the assumptions at the core of the schools’ argument: (1) that SAAB/genitals determine sex, (2) that the plaintiffs are therefore “girls,” and (3) that letting the plaintiffs use boys’ bathroom means that cisgender boys would be forced to share the bathroom with “girls.”[189] The Adams en banc court readily adopted these same assumptions, regurgitated the schools’ arguments, and transformed these arguments into law, without needing to contend with counter-analyses from the pro-trans decisions.

First, the Adams en banc court, like the schools, treated Adams’ equal protection challenge as one to the constitutionality of separating bathrooms based on “biological sex.”[190] The court found no meaningful difference between an as-applied challenge to the bathroom rule’s definition of sex and a challenge to the existence of sexed bathrooms.[191] These two claims are conceptually distinct. The court was only able to equate them because it made the same assumptions about the meaning of sex that the schools did: that sex means SAAB in all legal contexts and as applied to every person.[192] For the court and the schools, a decision in favor of Adams is the same as a decision ending sexed bathrooms because “sex” is SAAB. Rather than explaining why SAAB, and specifically, Adams’ SAAB, should determine sex for bathroom purposes, the court dismissed any possibility that Adams’ SAAB might not be dispositive of his sex and summarily concluded that his gender identity, or any other aspect of his sex, was irrelevant.[193] Thus, not only did the court’s misconstrual of the plaintiff’s claim improperly turn this case into one that fits neatly within the canon, but it also answered the critical question in this case—whether SAAB should determine Adams’ sex for bathroom purposes—without any explanation or support.[194]

Reframing Adams’s claim as one that challenges sexed bathrooms, as opposed to the definition of sex, helped the court obscure the flaws in its analysis. By contorting the canonical cases to appear as if they directly applied to Adams’s claims, the court could characterize its conclusion as “obvious”: that the school’s justifications for the bathroom rule were important and that excluding “biological girls” from the boys’ bathroom was “clearly” related to those justifications.[195] This outcome is neither obvious nor correct, for the reasons explained in Part III.C. But in reaching this conclusion, the Adams court did not have to work very hard to brush aside the three conflicting court of appeals decisions.[196] Future anti-trans courts and litigants, now armed with a favorable en banc decision, will continue to make the same flawed arguments. And until a pro-trans decision confronts and rebuts these arguments, they will continue to characterize their conclusions as “obvious” applications of the canon.

III. Contextual Sex and Sex-Defining Laws

This Part explains how a contextual approach to sex can help produce doctrinally and normatively sound decisions in sex-defining cases. Part III.A introduces and explains the idea of contextual sex and then discusses how a contextual approach flows directly from existing equal protection doctrine. Part III.B explains how such an approach provides an antidote to the flaws in the pro-trans decisions discussed in Part II. Part III.C applies a contextual approach to a bathroom case like Grimm, Adams, or Whitaker: an as-applied challenge to a bathroom rule that defines sex based on SAAB/genitals.

A. Contextual Sex

1. Contextual Sex in General

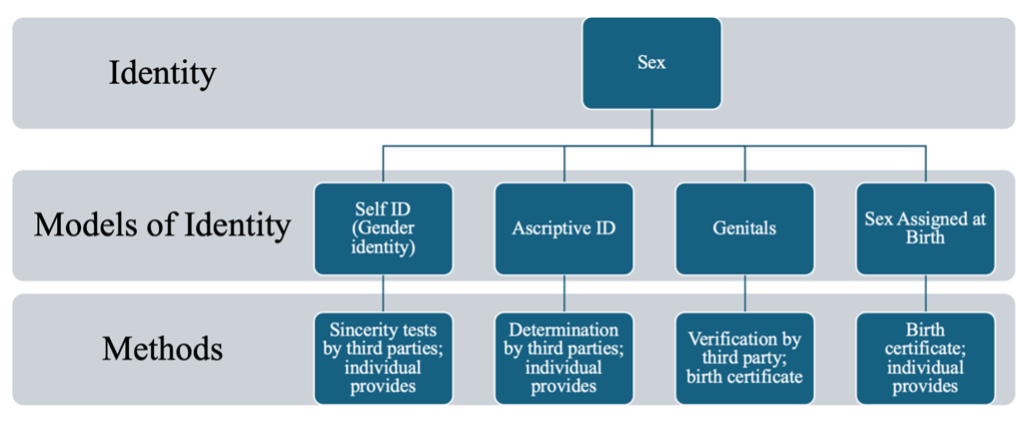

A contextual approach to identity means that legal identity determinations are, or should be, driven by the goals or functions of the relevant law. Scholars have used the concept of contextual identity to both describe how some areas of law already treat identity[197] and how law should treat identity.[198] The literature on contextual sex has become significantly more robust over the last decade (although these scholars do not always use the language of “contextual sex”).[199] Professor Jessica Clarke, a leading voice in the area, describes a contextual approach to sex as one that resists universal definitions of sex and gender and instead defines them “with attention to each legal context.”[200] In other words, a contextual approach to sex identity aligns the law’s definition or deployment of “sex” with the purpose of the law at issue. Under this approach, sex has no pre-legal meaning that can be directly imported into all legal contexts.[201] Rather, the meaning of sex depends on why the law is using sex in the first place. Whether a law should define sex by gender identity, SAAB, hormone levels, genitals, something else, or nothing at all depends on the purpose of the law.[202] This approach, therefore, understands sex as capable of being disaggregated into what this Article calls “models.”[203] Four popular models of sex are shown below.

Figure 1: Models of sex

Sex can be understood as someone’s gender identity, i.e., their self-identification. Ascribed sex is the sex others assign to someone based on what the observer knows, or thinks they know, about that person’s sex.[204] A genital-based model of sex determines sex based on the person’s genitals. [205] Sex assigned at birth (SAAB) is the sex medical professionals assign to babies when they are born, typically based on what the baby’s genitals look like.[206]

These models of sex identity are illustrative, not exhaustive; other common models of sex include hormones,[207] internal reproductive organs, and chromosomes. Moreover, different models of sex can overlap and can be co-constitutive. For instance, a person may identify as a woman publicly (self-identification) which, in turn, affects how third parties perceive their sex (ascriptive identity).

Different models of sex may or may not align within a particular individual. Transgender identity is often conceptualized as a misalignment of SAAB and gender identity,[208] but for many transgender people, other models of sex (like ascriptive sex and gender identity) do align. And although cisgender individuals’ SAAB typically aligns with their gender identity, other models of their sex may not.[209] For example, some cisgender women do not have XX chromosomes[210] and others are not always perceived as women,[211] while some cisgender men have similar testosterone levels as cisgender women[212] and others might have secondary sex characteristics that are commonly associated with women.[213] Thus, a central aspect of a contextual understanding of sex identity is its rejection of any assumptions that any two models of sex align, either in general or within one specific individual.

Because this approach does not presuppose alignment of any two models of sex, it does not consider “biological sex” to be a legitimate model of sex. “Biological sex” could refer to chromosomal sex, SAAB, genital-based sex, hormones, or something else. But many laws that use this term do not typically define it with either specificity or consistency.[214] Instead they often use it to obscure their precise definition of sex, operating under an unspoken assumption that all of these “biological” models of sex always align.[215] A contextual approach requires the state to define “biological sex” with precision and to specify the model or models of sex to which “biological sex” refers.

2. Contextual Sex and Equal Protection

A contextual approach to sex in sex-defining cases directly maps onto and flows from existing equal protection doctrine. The second prong of an intermediate scrutiny analysis tests the fit between the state’s end and the means employed to achieve that end, and as explained in Part I, the means in sex-defining cases is the state’s definition of sex.[216] A contextual approach is performing the same inquiry as the ends-means prong: determining whether the state’s definition of sex (i.e., the model of sex) aligns with the purpose of the law.[217] The intermediate scrutiny test modifies a contextual approach only in dictating how closely aligned the definition of sex and the state’s objective need to be. Here, the definition must “substantially relate” to the state’s goal.[218] Put simply, a contextual approach to sex is the ends-means analysis for sex-defining laws under intermediate scrutiny.[219]

Because the question of fit on the ends-means prong is between the model of sex and the law’s purpose, it is worth highlighting the distinction between models of sex identity and methods to determine sex identity under a particular model. There are many possible methods for determining sex under each model. For example, suppose a law uses self-identification (gender identity) to determine sex. There are several methods state actors could employ to determine how someone identifies their sex. They could simply ask the person how they identify (“What is your sex?”). They could examine how the individual has previously identified their sex (like looking to the person’s sex selection on the prior Census). Or they could have third parties determine if their self-identification is sincere—like having the person take a lie detector test. A sampling of methods that can be used to determine sex under four different models is shown below.

Figure 2: Methods to determine sex

Each method has its own set of tradeoffs. Some methods may predict the particular model of sex more accurately or be easier and less expensive to administer, while others are more respectful of bodily autonomy, privacy, and dignity. For example, consider different methods for determining gender identity. Asking people to identify their sex is minimally intrusive but somewhat costly to administer. Looking to individuals’ sex selection on the previous Census is less burdensome to administer but may not be as accurate, since some people may have changed how they identify since the last Census. Subjecting individuals to sincerity tests is costly to administer and extremely intrusive on individuals’ privacy, though, in theory, may increase accuracy.[220] This Article does not fully evaluate which methods are best for each model.[221] Nor does it suggest that methods of determining a model of sex are irrelevant to analyzing a law’s constitutionality. Rather, this Article highlights the conceptual distinction between methods and models in order to clarify the ends-means inquiry: specifically, to make clear that the relevant means in the end-means analysis are the models of sex, not the methods, and the primary question of fit is between the model and the law’s goal.[222]

Taking these previous points together, a contextual approach to sex applied to an equal protection challenge to a sex-defining law would proceed as follows. First, a court would identify the precise model of sex the state is using. Sometimes, this model can be easily gleaned from the law itself: for example, a law may explicitly define sex as SAAB. Other times, like in the bathroom cases, the state is less transparent about the model it is using and instead deploys imprecise or vague definitions of sex like “biological sex.”[223] In these circumstances, a court would need to determine the specific model or models of sex to which “biological sex” refers.[224]

Once the court has identified how exactly the state is defining sex, it can then square up the question presented, using the state’s exact definition of sex as the relevant means. For example, suppose an all-women’s public university defined “woman” for the purposes of admission as someone who has XX chromosomes. If a transgender woman (with XY chromosomes) was denied admission and brought an equal protection challenge to this policy, the question presented would be whether the state’s chromosome-based model of sex is substantially related to an important governmental interest.

If the law’s definition of sex does not substantially relate to the state’s interests, the law fails the ends-means prong of intermediate scrutiny and is unconstitutional.[225] The ends-means prong is satisfied if the model of sex does substantially relate to the state’s goal. But a court’s analysis would not stop there: satisfying the ends-means prong does not mean that the law survives intermediate scrutiny. Even if the model of sex perfectly aligns with the law’s purpose, that purpose still must be sufficiently important. [226] Laws with blatantly unconstitutional purposes can employ a model of sex that aligns with those purposes. For instance, imagine that a state passed a law defining marriage as between one “man” and one “woman.” The law defined “woman” as someone who had a vagina and “man” as someone who had a penis. The state’s interest behind the law was to ensure that married couples could have penetrative, penis-vagina sexual intercourse.[227] This law satisfies the ends-means test because the model of sex aligns with the law’s goal: defining sex based on genitals is the best way to advance the goal of promoting this particular type of sexual intercourse within a heterosexual marriage.[228] But the tight fit between the law’s goal and a genital-based model of sex does not mean the law is constitutional. The state’s goal of promoting penis-vagina intercourse in heterosexual marriage is not a permissible goal for several reasons, at least under existing law.[229]

Moreover, a severe misalignment between the model of sex and the purpose of the law might indicate that the law’s stated purpose is pretextual and obscuring the law’s actual purpose. Under intermediate scrutiny, courts need not accept that the stated purpose of a law is the actual purpose behind the law and can dig deeper.[230] Courts go about determining the actual purpose behind a law in a variety of ways.[231] Most relevant here is a gross lack of fit between the means and ends: when a law’s means are so vastly unrelated to the stated governmental interests, this can indicate that the government’s stated interests may be masking its more nefarious actual purpose.[232] So, a law that employs a definition of sex that does nothing to advance its stated purpose or actively undermines its purpose suggests that the state has alternative, unarticulated motives behind the law. Examining which interests such a definition of sex actually advances, rather than the stated interests, can reveal the actual purpose of a law.[233]