Visiting Judges

Despite the fact that Article III judges hold particular seats on particular courts, the federal system rests on judicial interchangeability. Hundreds of judges “visit” other courts each year and collectively help decide thousands of appeals. Anyone from a retired Supreme Court Justice to a judge from the U.S. Court of International Trade to a district judge from out of circuit may come and hear cases on a given court of appeals. Although much has been written about the structure of the federal courts and the nature of Article III judgeships, little attention has been paid to the phenomenon of “sitting by designation”—how it came to be, how it functions today, and what it reveals about the judiciary more broadly.

This Article offers an overdue account of visiting judges. It begins by providing an origin story, showing how the current practice stems from two radically different traditions. The first saw judges as fixed geographically, and allowed for visitors only as a stopgap measure when individual judges fell ill or courts fell into arrears with their cases. The second assumed greater fluidity within the courts, requiring Supreme Court Justices to ride circuit—to visit different regions and act as trial and appellate judges—for the first half of the Court’s history. These two traditions together provide the critical context for modern-day visiting.

The Article then presents a thick descriptive analysis of contemporary practice. Relying on both qualitative and quantitative data, it brings to light the numerous differences in how the courts of appeals use outside judges today. While some courts regularly rely on visitors for workload relief, others bring in visiting judges to instruct them on the inner workings of the circuit, and another eschews having visitors altogether in part because the practice was once thought to be used for political ends.

These findings raise vital questions about inter- and intra-circuit consistency, the dissemination of culture and institutional knowledge within the courts, and the substitutability of federal judges. The Article concludes by taking up these questions, reflecting on the implications of visiting judges for the federal courts as a whole.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

In February 2015, the Ninth Circuit issued an opinion in a closely followed insider-trading case, United States v. Salman.[2] The issue at hand—whether evidence of a family relationship between the insider and the “tippee” is sufficient to show that the insider received a personal benefit when passing on the insider information[3]—was a point of particular interest, since a major case in the Second Circuit, United States v. Newman, had recently held such evidence to be insufficient.[4] The Ninth Circuit ultimately rejected the Second Circuit approach, thereby creating a circuit split on the issue.[5] But what made the story truly riveting was the author of the Salman opinion: Jed Rakoff, a district judge for the Southern District of New York[6] and an outspoken critic of the Newman decision,[7] who was sitting by designation. Regarding the Second Circuit’s earlier decision, Judge Rakoff wrote on behalf of the Ninth Circuit that “we would not lightly ignore the most recent ruling of our sister circuit in an area of law that it has frequently encountered,” but “[o]f course, Newman is not binding on us.”[8]

It is astonishing that a district judge for the Southern District of New York—whose opinions are ordinarily subject to reversal by the Second Circuit—can author an opinion for the Ninth Circuit creating a conflict with his own reviewing court. Even more astonishing is that this conflict produced Supreme Court review, and that the visiting judge’s opinion was ultimately upheld.[9] But the episode is not entirely anomalous. Despite the fact that Article III judges are nominated for particular seats on particular courts,[10] the federal system functions with judicial interchangeability virtually every day. Hundreds of judges each year sit by designation on other federal courts, whether in different locations or different points in the judicial hierarchy.[11] Officially, the practice of “borrowing” judges exists as a way to ease particularly high workloads.[12] If a given circuit has a relatively large caseload one year and could use relief, judges from other circuits, district judges from both within and outside of the circuit, and other Article III judges may then be fielded to assist the court.[13] From September 2016 to September 2017, visiting judges of all kinds were involved in deciding approximately 4,300 federal appeals.[14] Nearly 2,000 of those appeals were decided on the merits after oral argument—representing almost 30 percent of such cases in the federal courts.[15]

Although much scholarship has examined the structure of the federal courts and the nature of Article III judgeships, almost none has focused on the phenomenon of visiting judges.[16] The handful of existing articles on the subject have focused on important but relatively narrow aspects of sitting by designation. For example, a few have examined how different types of visitors perform—mainly by looking to how often they write majority opinions or dissents as compared to “home” judges.[17] Yet larger questions loom about the practice, and more broadly about our court system and the judges who populate it. How did the federal courts come to have visitors? What was the original rationale, and was there resistance to having judges from outside the court help to decide—and even sometimes cast the deciding vote in—important matters? How does the practice function today? How do judges—both those who have received visitors and those who have “gone abroad,” so to speak—view sitting by designation? To what extent do courts rely on visitors, and is that reliance uniform or does it vary from court to court? This Article takes up these questions, and in so doing, seeks to offer a broader descriptive and normative account of visiting judges and the presumed interchangeability of Article III judges on which the practice rests.

Part I begins by tracing the origins of judges sitting by designation. The direct line runs back to the early nineteenth century. Prior to this point, federal lower court judges were understood to be “immobile”[18] or even “frozen,”[19] as they were not permitted to sit on a court apart from their own.[20] But in 1814, Congress for the first time authorized a visiting arrangement, when the judge for the Southern District of New York was permitted to sit as a judge in the Northern District to assist a Northern District judge in poor health.[21] This arrangement was then generalized in 1850, when Congress provided that judges could be “certified” to a nearby court to offer assistance.[22] The measure was understood to be an emergency stopgap, however—to be used only in extreme cases of illness or disability.[23] In the decades that followed, the practice was expanded to assist with workload pressures more generally.[24] But when former-President Taft proposed a system of “judges-at-large”—in which a number of floating judges would be placed with various courts as needed—he met significant resistance.[25] Taft eventually abandoned his proposal for a “flying squadron of judges”[26] and instead, as Chief Justice, helped create what became the Judicial Conference of the United States, which coordinates the assignment of judges from one circuit to another.[27] And so it has remained that judges can assist courts beyond their own, though they must be tethered to a particular district or circuit.

A second history is yet more distant, but still a relevant precursor to visiting in the present day: circuit riding. Though not discussed extensively in the literature,[28] Supreme Court Justices were required to “ride circuit” for the first 120 or so years of the Supreme Court’s existence.[29] This practice entailed physically visiting, and then helping to constitute, the circuit courts across the country.[30] This lineage is relevant not only because it shows how certain federal judges were not always “fixed” geographically, but also because it reveals a tradition of fluidity within the court structure. Members of the Supreme Court were Justices during part of the year, but then circuit judges alongside (similarly “moonlighting”) district judges in the remainder.[31] In short, judges have long been pulled from their particular offices and brought together to configure new courts.

Part II moves from the past to the present, and focuses on where visitors are making the largest contribution today: the courts of appeals.[32] Relying on qualitative data from inside the judiciary, this Part provides a detailed descriptive account of the use of visiting judges at the federal appellate courts. This description is based on interviews with thirty-five judges and senior members of the clerk’s offices of five circuit courts. What emerges from these interviews is an interesting picture. None of the interviewed judges relished the thought of having strangers join them on the bench; all noted that they would prefer to sit with their own colleagues.[33] And indeed, one of the courts in this study had stopped using the practice altogether.[34] But most of the judges generally acknowledged the workload benefits that came with the practice, even while quite a few noted the limits of receiving visitors.[35]

And yet the meaningful benefit to the judges went beyond the caseload relief so often stated as the rationale for visiting. Many emphasized the opportunity for judges, particularly new district judges, to learn about the inner workings of the court and the appellate judges themselves. As several judges described it, they were in a “teaching relationship” with the new judges, and could not only convey the mechanics of the appellate process, but could also educate the district judges about the appellate culture.[36] Many of the judges noted that the benefits could run both ways, and so it might be helpful for them to sit by reverse designation and visit the trial court. But none of the circuits surveyed here had such a tradition (several judges stated that they did not know enough to take on the assignment and feared ultimately being reversed).[37]

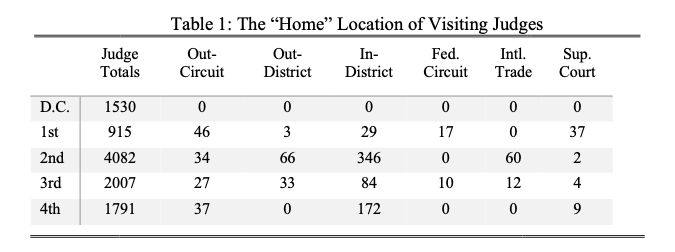

Part III moves from the qualitative to the quantitative, using data on visiting judges to further the descriptive analysis of contemporary practice. Publicly available information provided by the Administrative Office of the United States Courts confirms that some of the circuits—such as the D.C. Circuit—do not rely on visiting judges.[38] It also confirms that while many district judges routinely visit the courts of appeals, very few courts of appeals judges visit district courts.[39] To further fill in the picture of modern day visiting, this Part looks to a unique dataset, created from the oral argument panels of all twelve regional circuits over a five-year span. These data can show, for example, not simply how many district judges a particular circuit relied on, but specifically where those judges hailed from. This Part presents those findings, and reveals significant inter and intra-circuit differences.

Finally, Part IV moves to the normative and considers the implications of these findings for the federal courts. First, it addresses questions of consistency across circuits. Divergent practices concerning visiting judges would be understandable if visitors were brought in solely for workload relief. (Indeed, from this standpoint, it would be questionable if courts with relatively low caseloads routinely borrowed other judges.) And yet, if there are recognized net benefits to having district judges sit by designation for training purposes, is it problematic that only some of the circuits follow the practice?

Second, apart from inter-circuit consistency, Part IV examines the question of inter-district (or intra-circuit) consistency. The findings of the quantitative study reveal significant discrepancies regarding where the visitors are drawn from—even among visiting district judges from within a given circuit. There are good reasons for some of these differences; it is plainly easier as a logistical matter, and far less expensive, to fill seats with judges from across the street than from several hundred miles away. And yet, if sitting by designation is important for learning the culture and norms of the circuit, and potentially can even lower one’s reversal rate over time,[40] it may well be problematic that there are such differences in where the visitors are visiting from.

Third and finally, Part IV considers matters of consistency across the court hierarchy. If it is useful for district judges to sit on the court of appeals to learn firsthand how that court functions, one may well wonder about the practice of reverse designation—whether it would be beneficial for appellate judges to try cases. There are no doubt risks associated with this practice that do not exist with visiting the court of appeals (namely, at the court of appeals there are two other judges to assist the visitor). But if there are important benefits to be gained—as the judges in the qualitative study suggest there are—it is worth asking if the practice of visiting should be expanded in this direction.

Ultimately, judges sitting by designation is more than a curious facet of modern-day courts. What began as a means for self-help within the system—a way for some courts to assist other courts in need—now carries out other, critical functions. It is important to understand this practice more fully, and what it says about the nature of judging and the federal courts as a whole.

I. Two Historical Accounts

The history of judges sitting by designation is a tale of two substantially different accounts of Article III judgeships. The first is the direct line to modern-day visiting, and begins with a conception of judges as fixed to particular courts. In the early days of the federal judiciary, lower court judges were expected to serve only in the office to which they had been nominated and confirmed; there was no visiting to speak of.[41] But since 1814, Congress has permitted judges to sit by designation, and that permission has expanded over time.[42] Specifically, it has grown to encompass different reasons for visits, beginning with the physical disability of a single judge and moving outward to workload relief for the court as a whole. Furthermore, it has grown to encompass visiting across the entire federal judicial system, with visitors initially coming from the same circuit to now any Article III court. But this expansion has faced limits—attempts in the early twentieth century to create a set of judges-at-large to assist other courts were squarely rejected.[43] Thus, while this fixed-in-place view of Article III has become less rigid over time, it continues to see judges as necessarily tied to a particular court in a particular place.

Beyond this direct history, visiting should also be understood in relation to a more remote historical phenomenon: circuit riding. Between 1789 and 1911, the Justices of the Supreme Court rode circuit each year,[44] meaning that they traveled across the country and, alongside district judges, sat on circuit courts to decide cases.[45] The practice began in part out of necessity, as it would have been difficult to fund a new complement of circuit court judges.[46] And yet it also had recognized benefits, as it was thought that the Justices would bring a great deal to, and take something from, the courts they were visiting.[47] The view of Article III judges associated with circuit riding thus sees them as mobile, both geographically and also within the federal judicial hierarchy.

This Part traces these two lineages of modern-day visiting. It begins with an account of how sitting by designation was born and grew up. It then describes the historical arc of circuit riding as a practice. Finally, this Part concludes by considering how visiting today fits within these lineages.

A. The Frozen Nature of Judgeships

In one respect, the first quarter century of the federal courts represented an age of immobility. As courts scholar Peter Graham Fish put it, “[f]or many years the organization of the federal courts was based not only on frozen district boundaries but on frozen judges within those confines as well.”[48] Those frozen district boundaries were set by the first Judiciary Act in 1789, which divided the country into three circuits[49] and, within those, thirteen districts.[50] Each district was authorized one district judge.[51] (The circuits, for their part, which had a mix of original and appellate jurisdiction,[52] were to be constituted by a single district judge and two Supreme Court Justices.[53]) Throughout this time, lower court judges were not permitted to sit outside of their own district.[54] Even if a district judge recused himself from a particular case (meaning, effectively, that there was no judge in the district to hear the case), that case was then transferred out to the next circuit court—no outside judge stepped in.[55] Judges were appointed and confirmed to particular seats on particular courts,[56] and that was where they served.

As with so many things, change came from perceived necessity.[57] As Professor Stephen Burbank, Judge S. Jay Plager, and Professor Gregory Ablavsky have written, throughout this time the courts lacked any sort of provision for disability or retirement.[58] Accordingly, when a judge was not keeping up with his workload due to illness, solutions were limited—and dismal at that. In theory he could be removed (following conviction after trial on articles of impeachment)[59] or he could resign (without remuneration).[60] Congress could also create another judgeship, but such a measure would have been considered drastic—an expensive enlargement of what was then a very small federal judiciary.[61] And so although it has been suggested that judges were not authorized to visit other courts until 1850,[62] it is perhaps not surprising that a visiting scheme arose even earlier out of the need of a judge and his district.[63]

A close historical examination reveals that the judge for the Southern District of New York was authorized to hold court for the judge of the Northern District when those districts were first created[64] in 1814[65]—apparently due to the ill health of Judge Tallmadge of the Northern District.[66] Judges Tallmadge and William P. Van Ness (locally known as Aaron Burr’s “second” in his duel with Alexander Hamilton[67]) had been serving together as the two judges for the District of New York since New York obtained a second judgeship in 1812.[68] Then when Congress split the District in “An Act for the better organization of the courts of the United States within the State of New York,” Judge Tallmadge was assigned to the Northern half and Judge Van Ness to the Southern half. [69] The same Act “made [it] the duty” of Judge Van Ness to hold district court “in the said northern district, in case of the inability, on account of sickness or absence, of the said Matthias B. Tallmadge to hold the same.”[70]

One might wonder why Congress created two separate districts within New York, if only then to permit (and in fact, require) one judge to assist the other. According to H. Paul Burak, former Chairman of the Special Committee on the History of the Federal Courts, there was “[a]nimosity between the two judges,” which “soon led Tallmadge to seek the separation of the State into two districts so that he might serve in one, unfettered by Van Ness.”[71] Judge Tallmadge’s lobbying efforts apparently paid off, though he may have had buyer’s remorse. Judge Tallmadge technically remained a judge of a separate district, but once Judge Van Ness was authorized to assist him, the latter conducted the majority of the work in the northern district as well as all the work in his own.[72]

To be sure, the Act of 1814 can be seen as representing a modest allowance; a single judge was given permission to visit a single court.[73] But it was a beginning in the history of visiting judges. As Judge Charles Merrill Hough remarked 120 years after the Southern District’s organization, “[w]hile the right of the District Judges in New York to sit as well in one District as the other, was a concession to Tallmadge’s physical weakness, it marks the beginning of the system of using Judges out of their own Districts in order to relieve press of business.”[74]

Judges Van Ness and Tallmadge were not quite done playing their part in the history of judicial administration. In 1817, a temporary session law specified in general terms that the United States District Court for the Northern District would be held by the judge of that court and the judge of the Southern District (and bestowed upon the judge of the Southern District an additional thousand dollars per annum as compensation).[75] As that law was set to expire after only one year, the House introduced a bill in March of 1818 “[r]especting the Districts Courts of the United States within the state of New York,” which directed the judge of the Southern District to “hold the said court, in, and for, the said northern district, . . . with the like power and authority, in all respects” in the event the judge of the Northern District was unable to preside “on account of sickness, absence or otherwise.”[76]

However, the passage of the bill was not entirely smooth. Upon its second reading, Representative John Forsyth of Georgia asked why the House was being called upon to legislate “so frequently” for the courts of the District of New York, and indeed why it had to be “an exception to the general judiciary system of the United States.”[77] When told this exception was due to Judge Tallmadge’s ill health,[78] Forsyth said pointedly that “[w]hilst his health did not allow him to attend his official duties, it allowed him to travel from New York to Charleston and back every year.”[79] Aside from throwing this bit of shade upon the judge of the Northern District, Forsyth went on to ask about the appropriate remedy for the judge’s apparent illness: “If the state of his health detain him from performance of his duties, and he do not quit his office, it is in the power of the House . . . to apply a remedy by an impeachment . . . .”[80] The response that came back from Representative Hugh Nelson of Virginia was that the Judiciary Committee had considered the matter and “been of a different opinion” from Forsyth but that in any event, the bill at present would need to be passed “in order that the court should not cease to be held.”[81] Notwithstanding Forsyth’s repeated objections,[82] the bill ultimately passed.[83]

The episode surrounding the passage of the 1818 Act is interesting for what it reveals about the decision-making process behind continuing the visiting arrangement in New York. There was at least some concern about permitting this sort of visiting as it meant making an “exception” within the larger federal system.[84] The tension between wanting as limited a remedy as possible and not wanting special treatment for special (New York) courts would continue to surface in the history of the practice.[85] Returning to the limited possibilities judges and Congress faced in such situations,[86] it is noteworthy that Congress eschewed other potential responses. Contrary to Forsyth’s suggestion, it did not impeach and replace the judge who was not keeping up with his workload.[87] And though no one asked about an alternative possibility—creating another judgeship—Representative Arthur Livermore of New Hampshire went out of his way to note that the current plan would not create a new district or judgeship, and accordingly would “not . . . create any additional expense.”[88] It appears that Congress saw importing a neighboring judge as the best way (certainly the least politically contentious and most cost-effective way) to assist the court.

The use of visiting judges expanded significantly in 1850 when, for the first time, Congress created a general scheme that applied beyond any particular district. Once again, perceived need was the catalyst for creating the new law, and, once again, that need came from the state of New York. By the middle of the nineteenth century, one particularly well-regarded judge in New York had become overworked to the point of ill health.[89] Judge Samuel Rossiter Betts, who had been nominated to the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York by President John Quincy Adams in 1826,[90] had suffered the effects of a sharp increase in caseload.[91] And so, in 1850, Senator Bradbury of Maine introduced a bill “to provide for holding the courts of the United States, in case of the sickness or other disability of the judges of the district courts.”[92] The bill provided that in such circumstances, the circuit judge of the circuit in which the ailing district judge was located could designate another district judge within the same circuit to hold court.[93] If no circuit judge could make the designation, the President of the United States could then designate any district judge within the circuit, or any district within a circuit “next immediately contiguous” to the one of the sick or disabled judge.[94]

Senator Andrew Butler from the Committee on the Judiciary stressed the bill’s importance: “By the existing laws, if a district judge is sick, or unable from any cause to discharge his duties, there is no provision by which any other judge can be authorized to act in his place. The consequence is . . . he must break down.”[95] Turning then specifically to Judge Betts, the Senator said:

In New York the business has increased so much, as almost to break down the distinguished judge of that circuit (Judge Betts)—and we all know that he is distinguished for his ability and industry. He tries his best, and taxes his powers to hold all the courts he can, but his health is giving way; yet he hears five hundred causes in a year, and writes out, it is said, one hundred elaborate judgments. Now, it happens that sometimes he is sick, and then these causes accumulate and the cost is increased, so that the parties suffer by it.[96]

In an interesting move from a separation-of-powers perspective, the bill was then amended at the insistence of Senator Bradbury, the author of the bill, to read that the Chief Justice, rather than the President, would be authorized to detail a judge in the event that the circuit judge was not able to do so.[97] It then passed the Senate that same day.[98]

The legislative history from the House appears to show some concern over the bill. Representative James Brooks (not surprisingly of New York) spoke first on the matter, noting the situation with Judge Betts[99] and stating that he was “anxious” for the bill’s “immediate passage because of the state of public business in the city of New York.”[100] Instead, Representative George Jones of Tennessee successfully moved that the bill be referred to the Committee on the Judiciary.[101] His stated reason was that it contained “a very important provision, extending not only to New York, but to all the judges and courts of the country” and so warranted the consideration of the Committee.[102] The bill was reported out of Committee two months later, and it was noted that the Committee had decided to report a general bill rather than a special act to address Judge Betts’s situation.[103] The bill passed, creating for the first time the authority for any district judge to sit by designation on a court that was not his own, provided that he was assisting a disabled judge and that he was not straying far.[104]

The use of visiting judges steadily expanded from that point on, with the next expansion occurring along the line of accepted reasons for seeking assistance. In 1852, the original act providing for holding court in the case of sickness or disability of a judge was amended to authorize the relevant circuit judge or Chief Justice to designate a visitor if it appeared to their satisfaction that “the public interests, from the accumulation or urgency of judicial business in any district, shall require it to be done.”[105] The new law went on to specify that the visiting judge would enjoy “the same powers within such district as if the District Judge resident therein were prevented by sickness or other disability from performing his judicial duties.”[106]

This expansion represented an important shift in the practice of visiting judges. Not only was Congress increasing the instances in which judges could be called upon to aid a particular court, but it was widening the lens of inquiry. Visitors no longer needed to be substitutes, coming to court to assist a particular judge. They could now come to provide relief to the court itself.

It seems that district courts in New York were, at least in part, once again the impetus for the law. In reporting on the bill to the Senate, Senator Butler—who had spoken in favor of the 1850 Act[107]—provided the context for the amending legislation.[108] He began by reporting that the original act “thus far has worked well,”[109] and that there was no sign that it had been overused.[110] Senator Butler went on to note that the bill at hand would be a welcome next step since it would “allow the judges of the district courts of the State of New York to call in the aid of other judges.”[111] This arrangement would be beneficial, according to the Senator, as “[t]here are the judges of the district courts of the States of Vermont and New Hampshire . . . who have but very little to do, and might, when requisite, go to New York and do this business very well.”[112] The bill ultimately passed in both houses without incident.[113]

The next several decades saw significant changes to the organization of the federal courts, and the reliance on visitors.[114] In response to an increasingly congested Supreme Court,[115] Congress in 1891 created a new tier of intermediate appellate courts.[116] The Circuit Court of Appeals Act (known in common parlance as the Evarts Act) created a set of courts that would take appeals as of right from the federal district courts, and be reviewed by the Supreme Court.[117] (Though the original circuit courts would live on, their jurisdiction was curtailed considerably—to wit, they no longer had appellate jurisdiction over the district courts—and they would ultimately be abolished two decades later.[118]) Unlike the original circuit courts when they first came into existence, the circuit courts of appeals were bestowed with a dedicated set of judges, but not a full set.[119] Specifically, the courts were authorized two judges even though Congress expected them to decide cases in panels of three.[120] The third jurist was to be drawn from either “the Chief-Justice and the associate [J]ustices of the Supreme Court assigned to each circuit” or “the several district judges within each circuit,”[121] thereby keeping some family resemblance to the old circuit courts.[122]

And so it was that the federal courts of appeals had a visiting arrangement embedded within them from the beginning. District judges from the circuit could visit “up,” and Supreme Court Justices could visit “down.” But the visiting arrangement was not without limits. As with visiting between district courts at the time,[123] visitors could not come from all over the country. This limitation would eventually give way, with Congress proceeding with the district courts first.

Indeed, the practice of visiting judges saw its next major expansion roughly fifteen years later, regarding where a district court visitor could come from. In an Act of March 4, 1907, Congress broadened the pool of available designees, providing that if for “sufficient reason” it was “impracticable” to appoint a judge of a district within the same circuit, the Chief Justice could “designate and appoint the judge of any other district in another circuit to hold said courts.”[124] This amending law referred only to situations in which the judge being replaced was disabled, and did not extend to situations in which a court simply needed assistance for workload relief. But this amendment still represented a sizable shift. For the first time in the history of the federal courts, a judge from the Northern District of California could travel to sit by designation as a judge of the District of Maine.

The matter did not create much controversy. Both the House and Senate Judiciary Committees unanimously recommended that the bill pass.[125] Only in the House was there some pushback on the floor—Representative James Mann from Illinois, reserving the right to object, inquired as to what the bill would accomplish.[126] Thomas Jenkins from Ohio responded that it was a “very necessary bill,” and that “our attention has been called to many places throughout the United States where they are really suffering to-day for the want of the presence of a judge and can not have him because under the law an assignment can not be made.”[127] William Sulzer of New York then stated that it “is a good bill and it ought to pass,”[128] prompting Mann to withdraw his objection.[129] The measure passed.[130] (It should not be surprising that no similar measure was passed for the courts of appeals. As those courts had fairly large pools to draw upon already and only required a quorum of two to decide cases,[131] they did not face the need of their sister courts at this time.)

If one thinks of the expansion of permitting visitors at the district court as a natural progression—it began with local assistance for disabled judges,[132] then included local assistance for workload relief,[133] then included “foreign” assistance for disabled judges[134]—it is only logical that the next push was for “foreign” assistance for workload relief. And so it was, at least in part. In the words of Professor Fish, “[g]eneral intercircuit assignments received a major impetus” in 1913.[135] The judges in New York were once again the focal point of the story. Having a particularly large workload, the senior circuit judge of the Second Circuit (what we today call the chief judge[136]) had been angling for the ability to call upon judges from outside the circuit who were not “fully occupied” to assist the district courts.[137] Congress responded with the Act of October 3, 1913.[138] That Act provided that whenever the senior circuit judge certified that it would be “impracticable” to designate a judge from within the circuit to assist with the “accumulation or urgency of business,” the Chief Justice could “if in his judgment the public interests so require[d],” appoint a judge from another circuit to sit by designation.[139] But rather than create a general scheme for all courts, Congress gave only the Second Circuit permission to call upon foreign judges to help with a rising workload.[140]

The original bill considered by the Senate actually was intended to apply to all circuits “[w]henever it shall be certified by any senior circuit judge of any circuit.”[141] But this scheme soon fell to, in the words of then-Professor Felix Frankfurter and James Landis, “sectional prejudice.”[142] While it seemed unproblematic for New York to have visitors from afar, “totally different feelings were aroused by the thought of eastern judges holding court in southern or southwestern districts,”[143] and Congress subsequently amended the bill to make it applicable only to the Second Circuit.[144] When members of the House debated the bill, there was a question about whether it might not be preferable to have a uniform scheme.[145] Representative Henry Clayton of Alabama responded by saying that “[i]t seemed that [the bill] could not pass the Senate without this amendment making it applicable alone to the second circuit”[146] and further urging the House to pass the bill in any event since the situation in the Second Circuit was dire.[147] Ultimately his position won the day.[148]

Not surprisingly, other circuits soon wanted similar assistance for their district courts. The senior circuit judge of the Sixth Circuit, Arthur Denison, presented a clever argument in an attempt to gain the same relief given to the Second Circuit. Specifically, he argued that one could combine the 1913 Act with the general provision that foreign judges could assist in instances of disability to create the general power of the Chief Justice to assign foreign judges for workload matters.[149] The Chief Justice, unfortunately, did not look favorably upon such alchemy. Indeed, he flatly refused to allow a judge from Texas to sit by designation in the overwhelmed federal district court in Detroit on the ground that by specifying the Second Circuit and the Second Circuit alone in the 1913 Act, Congress clearly had not intended to create a common scheme for all federal courts.[150] As a result, outside of the Second Circuit, the assignment power of the Chief Justice was used only in the case of a given judge’s illness or disability.[151]

The decade that followed proved to be a critical time in the history of visiting judges, and indeed, judicial administration more broadly. Given the trajectory of the practice, and given the perceived needs of circuits beyond the Second, one might expect judicial reformers to have focused on pushing for the expanded use of drafting Article III judges. In fact, the years that followed the 1913 Act saw a much more radical proposal: a call for the creation of a new kind of judge—a mobile judge, who could come to the aid of courts in need.

Soon after leaving the presidency, William Taft became an outspoken proponent of creating a new set of judges-at-large for the federal judiciary.[152] The concept of itinerant judges was not new to Taft. During his time in office, Congress had created the short-lived United States Commerce Court,[153] which was staffed with judges who would sit on that court during part of the year and who could then assist other circuits as needed.[154] George Wickersham, the Attorney General under Taft, purportedly saw the court as the “first step” toward, in Professor Fish’s words, an “administratively integrated federal judicial system.”[155] The Commerce Court, though, was not long for this world—only a few years after it was created, Congress decided to abolish it.[156] The difficult question that emerged from the abolition of the court was what to do with the Article III judges who comprised it.[157] In a somewhat fitting conclusion, a few returned to their original courts while two others were eventually assigned to new ones.[158] And in the years that followed, Taft advocated for a broader version of the scheme.

In his 1914 “Address of the President” delivered at the annual meeting of the American Bar Association (as he was now President of that organization), Taft called for the creation of a set of judges-at-large.[159] After painting a picture of the federal judiciary in which some judges had “too much” to do and others “could do more,” Taft proposed a system “by which the whole judicial force of circuit and district judges could be distributed to dispose of the entire mass of business promptly.”[160]

Taft was sufficiently wedded to his proposal that “within hours” of being confirmed Chief Justice of the United States several years later, he wrote to Attorney General Harry Daugherty about judicial reform, including the system’s need for judges who could be dispatched to assist overworked courts throughout the country.[161] Around the same time, the Attorney General appointed a special committee to consider reform proposals for the federal judiciary, which ultimately made several recommendations that dovetailed with Taft’s plan.[162] Specifically, the committee recommended that Congress create district judges-at-large within each of the nine circuits, who could be assigned anywhere within the circuit by the senior circuit judge or anywhere throughout the country by the Chief Justice.[163] The committee further recommended that Congress create a judicial conference, which was to be made up of the Attorney General, Chief Justice, and all senior circuit judges, to meet regularly to consider matters of judicial administration, such as pressing workload issues.[164] Finally, the committee recommended expanding the use of visiting judges generally, such that the Chief Justice would have the authority to assign district judges to any court for any need.[165]

Congress soon considered bills to effectuate the committee’s proposals, but portions were quickly met with resistance. In particular, the provision to have what Taft had dubbed a “flying squadron of judges”[166] ran aground.[167] There were several noted concerns, including that the provision would vest the Chief Justice with too much authority, as he would have the power to direct the judges-at-large.[168] Another set of concerns seemed to echo the “sectional prejudice” that was on display when Congress earlier considered whether to expand the use of visiting judges.[169] As Professor Justin Crowe has written, Democrats in particular were wary of the impact a more centralized system of administration would have on “judicial localism.”[170] Taken at face value, the argument was that federal judges were not sufficiently fungible to assume each other’s roles across the country. And yet it is impossible to ignore the darker undertones, particularly given southern Democrats’ interest in avoiding “carpetbag judges” unfamiliar with the “conditions” in the South.[171]

An additional concern, as Professor Charles Murphy has noted, was that the proposal threatened to “upset established patronage arrangements.”[172] This concern was on display during a hearing with Chief Justice Taft and Attorney General Daugherty before the House Judiciary Committee regarding the proposed bills.[173] The committee was already considering the addition of several judgeships across the country and when pressed, the Attorney General conceded that if the bill to create judges-at-large were to pass, the need for some of the previously contemplated judgeships would be obviated:

Mr. Walsh [Representative of Massachusetts]: [W]e have bills on the calendar for an additional judge for the eastern district of Oklahoma . . . Also for Minnesota; and the committee has favorably considered an additional judge for the eastern and western districts of Missouri. That [with two judges-at-large] would give that circuit six additional judges?

Mr. Daugherty: Yes. If these 18 judges at large are provided, you might reduce Missouri . . .

Mr. Dyer [Representative of Missouri]: I do not see why you should pick on Missouri, Mr. Attorney General. [Laughter.][174]

In the end, Congress opted to create twenty-four standard district judgeships (including two in Missouri).[175] The provision for mobile judges died in the House Committee, and no attempt was made to revive it.[176]

What survived, however, were the other two main components of the committee’s proposal—to create the Conference of Senior Circuit Judges and to expand the practice of visiting judges. The latter provision in particular still faced a “rough[ ] road.”[177] Some of the opposition echoed arguments made against the provision to create judges-at-large, stressing the need for “local” judicial actors.[178] Representative William Francis Stevenson, Democrat of South Carolina, noted that he was not eager to have “carpetbag judges” moved around the country.[179] Specifically, he said, “[y]ou propose to take men from Maryland or Virginia or Pennsylvania and send them down to South Carolina, where the practice is different.”[180] He continued, “we of my State, at least, have had enough of the transportation of judges from a distance down there to make decisions that are revolutionary and which will overturn the decisions with reference to the rights of property and rulings of the courts.”[181]

Senator Lee Slater Overman, Democrat of North Carolina, likewise challenged the same provision on the grounds that it seemed too similar to the provision creating mobile judges:

That bill provided for roaming judges: it provided that a judge from North Carolina might be sent to try cases in Oregon, although the North Carolina judge does not know anything about the laws in Oregon or the conditions in Oregon or the methods of life there. Likewise, that bill provided that a judge might be taken from New Jersey and sent to North Carolina to try cases there, such a judge being entirely unacquainted with our laws and with our conditions. That is what is now proposed to be done—to sweep judges around all over the United States: to send them from one State to another. That proposition would not go down the throats of the Judiciary Committee.[182]

As it turned out, though the provision was indeed taken out in the Senate Judiciary Committee, the committee members later changed their minds and reinstated it with two provisos: The senior circuit judge of the “lending” circuit had to consent to the transfer, and the senior circuit judge of the “borrowing” circuit had to certify their need.[183]

Thus, a little over a century after Judges Tallmadge and Van Ness participated in the first visiting arrangement,[184] Congress allowed district judges from anywhere in the country to be certified to visit another court not simply because of the health of a single judge but for the health of a court and the public interest.[185] It further created a body of judges, referred to as the Conference of Senior Circuit Judges (today known as the Judicial Conference),[186] to serve as a key self-governing institution for the judiciary and help manage matters such as the caseload concerns of any individual court.[187]

It was this latter institution that twenty years later recommended the same courtesy be extended to the circuit courts. In the hearings before a Senate Judiciary subcommittee on the “designation of circuit judges to circuits other than their own,” D. Lawrence Groner, the Chief Justice[188] of the United States Court of Appeals, Washington, D.C. read a resolution of the Judicial Conference into the record:

The conference resolved that legislation was desirable authorizing the Chief Justice to assign circuit judges to temporary duty in circuits other than their own, the procedure of assignment to conform to that of existing legislation relating to the assignment of district judges to districts outside their circuits.[189]

The proposed bill did exactly that, following the same structure as the one created for district judges.[190] Justice Groner went on to note how well the visiting practice had worked at the district court—calling it a “matter of general satisfaction”—and how badly needed it was now for the appellate courts that were “very much overcrowded.”[191] Statements of various members of the bar and bench were read in favor of the bill—Judge Learned Hand went on record to say that “I am heartily in favor of this bill and think that it is a long overdue reform.”[192] George M. Morris, President of the American Bar Association, stated that “[t]his is such a sound idea. The only oddity about it is that it didn’t come forward long before it did.”[193] The bill allowing for circuit judges to visit other circuits, for reasons of the “volume, accumulation, or urgency of business” or “the disability or necessary absence” of a circuit judge, passed into law in the waning days of 1942.[194]

Stepping back, the original history of visiting judges tells an important story of the expectations of federal judges generally—that they were presumed fixed within their own court. It was only slowly and grudgingly that Congress eased the fixedness of federal judges when necessity called. And even then, there were (as there remain today) limitations on just how free and interchangeable Article III judges could be. While this picture may reflect our contemporary sense of the federal judiciary, it stands in marked contrast to a different (but ultimately related) practice within the federal courts: circuit riding.

B. The Fluidity of Circuit Riding

In one respect, the first 120 or so years of the federal courts represented an age of fluidity. Throughout this period, Justices of the Supreme Court rode circuit[195]—meaning that they traveled around the country for a substantial portion of the year to sit on the federal circuit courts.[196] As with visiting judges, the practice of circuit riding has not received extensive treatment in the literature,[197] though its history has been artfully traced before.[198] What follows is a brief account of circuit riding to contrast it with, and ultimately connect it to, sitting by designation.

The first Judiciary Act in 1789 established thirteen district courts to hear cases in the first instance[199] and a Supreme Court.[200] It further divided the districts into three circuits—the eastern, middle, and southern—and created courts of both original and appellate jurisdiction in those circuits, to be composed of two Justices of the Supreme Court and one district judge.[201] And so, from the beginning, the Justices had to perform their duties on the Supreme Court during one part of the year, and then ride out to the various federal circuit courts to decide cases as circuit judges in the remainder.[202]

One may well wonder why Congress created this particular arrangement instead of establishing a set of judgeships for the circuit courts. Circuit riding was meant to serve a host of functions,[203] including economy. Specifically, drafting the Justices and district judges to serve on the circuit obviated the need to pay for a new set of judges—a cost it was not clear the public fisc could bear in the early days of the country.[204]

But circuit riding was intended to provide benefits over and above cost savings. To wit, there was a perceived value in having Justices weigh in on questions of federal law at the appellate and even trial stages. As Joshua Glick has written, having Justices sit on the circuit courts helped ensure that “[authoritative] and correct answers be given to the critical legal questions” coming before the lower federal courts.[205] Ensuring that the “right” legal rules were fashioned was then meant to lead to two additional benefits. First, circuit riding was intended to bring about greater uniformity of federal law.[206] And second, the practice was meant to increase the public’s sense of the legitimacy of the federal judiciary.[207]

The benefits of circuit riding were intended to extend beyond what the Justices could bring to the circuit courts, though; they were meant to include what the Justices would bring back with them to their own Court. Specifically, by adjudicating cases and spending time in towns and cities outside of Washington D.C., the Justices were to become more familiar with the laws and customs of different localities.[208] (Some familiarity was assumed since initially Justices were assigned to the circuit where each had lived and practiced.[209]) This enhanced legal knowledge could then inform, and be used to improve, the Justices’ own decision-making at the Supreme Court.[210] In short, circuit riding cast the Justices as ambassadors—bringing information to and from various courts across the country.

Despite the numerous benefits that were meant to flow from circuit riding, the Justices strongly opposed the practice. In the words of Judge (then-Professor) David Stras, “[t]o say that most [J]ustices disliked circuit riding would be an understatement.”[211] First and foremost, the tours could be physically taxing, requiring extensive travel—indeed, the particularly treacherous southern circuit required two thousand miles of travel each year[212]—and all before the advent of railroads, cars, and airplanes. This was no small feat for the Justices, particularly some of the older members of Court.[213] In fact, the physical hardships endured during the early days of the practice led to health problems for several Justices.[214] Adding insult to injury, the Justices were required to pay for their own travel and accommodations during their tours, making the practice more unpopular still.[215]

In a different vein, the Justices believed that circuit riding created a problem with the structure of review. One of the main sources of cases to the Supreme Court was of course the circuit courts, meaning that the Justices would hear cases on appeal that some members of Court had previously heard below.[216] Although the Justices attempted to solve the problem by adopting an internal practice by which members of the Court would not decide any appeals that they had personally heard at the circuit court, such a solution was not feasible in every case—sometimes all of the Justices were needed for a quorum.[217] Given all of the challenges associated with circuit riding, the Justices lobbied for the abolition of the practice from the start.[218]

Congress soon made changes to the Justices’ assignments, but not the changes most of the Justices had hoped for. Based on the pleas of Justice James Iredell, who had been assigned to the perilous southern circuit, Congress passed the Judiciary Act of 1792, which stated that “no judge, unless by his own consent, shall have assigned to him any circuit which he hath already attended, until the same hath been afterwards attended by every other of the said judges.”[219] (It helped Justice Iredell’s cause that his brother-in-law was Senator Samuel Johnston of North Carolina.[220]) Though the measure was enacted to reduce the burdens that circuit riding placed on any one single Justice, it had the effect—or simply reflected the view—of an increased fluidity within the federal judiciary. No longer were Justices tied to the Circuit from which they originally hailed.[221] Following the Judiciary Act of 1792, any Justice could end up riding any of the circuits across the country—and in fact, the expectation was that they would rotate.[222]

Moderate relief for all of the Justices was soon forthcoming. The Judiciary Act of 1793 reduced the circuit riding responsibilities of the Justices by requiring only one Justice—instead of two—to sit on each circuit court.[223] But the burdens associated with circuit riding were still thought to be substantial, and even contributed to John Jay’s refusal of the Chief Justiceship following his stint as New York’s governor.[224]

Significant, even if temporary, relief came in the form of the Judiciary Act of February 19, 1801.[225] The “Midnight Judges Act,” passed by the outgoing Federalist Congress at the behest of President John Adams, abolished circuit riding and created sixteen circuit court judgeships (to be filled by Adams).[226] The Jeffersonian Republicans responded the next year by passing the Repeal Act of 1802, which abolished the new judgeships and required the Justices to take up their circuit riding duties once again.[227]

There were immediate questions surrounding the Repeal Act’s constitutionality.[228] Specifically, there were some who doubted whether Congress could require the Justices to ride circuit without separate appointments to, and commissions for, both courts.[229] Even Chief Justice Marshall apparently held this view.[230] And yet, despite misgivings, the Justices collectively decided that they should recommence their circuit riding duties in the fall of 1802.[231]

The constitutionality of circuit riding was soon put squarely to the Justices in Stuart v. Laird.[232] In what is now famous reasoning,[233] the Court rejected the arguments against circuit riding in a short opinion by Justice Paterson.[234] Rather than declare the practice clearly in line with the Appointments Clause, the Court instead decided that since the Justices had not earlier found circuit riding to be unconstitutional, the matter was settled and circuit riding should go on. In the words of Justice Paterson:

Another reason for reversal is, that the judges of the supreme court have no right to sit as circuit judges, not being appointed as such, or in other words, that they ought to have distinct commissions for that purpose. To this objection, which is of recent date, it is sufficient to observe, that practice and acquiescence under it for a period of several years, commencing with the organization of the judicial system, affords an irresistible answer, and has indeed fixed the construction . . . the question is at rest, and ought not now to be disturbed.[235]

Thus, a unanimous Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a practice that the Justices had pressed for so long to end—a practice that would endure for more than another century.

In the decades that followed, circuit riding became even more onerous as the Supreme Court’s own docket rapidly increased.[236] Congress, in response, made some modest adjustments to the Court’s obligations. For example, the Act of June 17, 1844 limited the amount of circuit riding each Justice was required to undergo in a given year.[237] Of particular note, the landmark Judiciary Act of 1869 created the only set of dedicated circuit judges at the time, and reduced the Justices’ circuit riding commitment to once every two years.[238]

A complete solution to the Court’s problems finally came in the form of the Evarts Act in 1891. As noted earlier, the Circuit Court of Appeals Act,[239] as it was formally known, significantly shifted the structure of the federal courts.[240] It created a new tier of intermediate appellate courts—the federal courts of appeals we know today.[241] Although the Evarts Act maintained the old circuit courts, they no longer had appellate jurisdiction over the district courts, thereby considerably shrinking their caseload.[242] Furthermore, under the Act, the Justices were made “competent” to sit as judges of the courts of appeals but they were not required to do so or to sit on the old circuit courts.[243] Accordingly, almost all of the Justices stopped riding circuit.[244] Chief Justice Fuller is the only notable outlier; he went on to hear more than forty cases on the Fourth Circuit in the twenty years that followed.[245]

Congress soon formalized what most of the Court had already brought into practice—the end of circuit riding. In the Judicial Code of 1911—Congress’s unification of statutes pertaining to the judiciary—Congress abolished the old circuit courts, and with it, circuit riding.[246] Thus, roughly a century and a quarter after it began,[247] the practice of Supreme Court Justices venturing out into various parts of the country to hear cases ended quietly. Despite some recent calls to resurrect the practice,[248] circuit riding in its traditional form remains a practice of the past, and not a fixture of our present.

Like the practice of visiting judges, circuit riding might be seen initially as a mere oddity of the federal courts—a curious habit that was ultimately dropped. But circuit riding in fact carries with it a great significance. Specifically, it demonstrates a fluidity of the federal system during the first 120 years of the Court’s existence along two key dimensions.

The first dimension is geographic. Justices were not always tied down to their posts.[249] Instead, the system relied upon them traveling to different courts across the states for a substantial part of the year. To be sure, the members of the Court did not have free reign; they had to go to the circuit to which they were assigned in a given year.[250] But it was understood that one was not meant to be “fixed”—one could be a Justice of Washington one part of the year, and then a judge of the southern circuit during the other part.[251] Circuit riding critically reveals that there was an assumed fluidity of place for these positions.

Second, circuit riding reveals fluidity within the judicial hierarchy. One was expected to be a Justice of the Supreme Court for part of the year and then a judge of the circuit court, sitting alongside a district judge, the next. Now, as some scholars have pointed out in regard to the constitutional challenges to the practice, circuit riding duties were meant to be encompassed in the role of Supreme Court Justices. That is, being a Justice meant also being a circuit judge.[252] While this is true, the critical point remains—it was built into the system from the very start that one could serve at the top of the judicial hierarchy and, in short order, serve as a trial or appellate judge on a different court.

Stepping back, it is certainly true in some respects that the federal judiciary was “frozen” during much of its early days.[253] But upon a close examination of past practice, it emerges that courts were allowed to borrow other judges quite early on—a practice that expanded over time to help ailing judges and later, overworked courts. And from circuit riding, it is clear that there was some interchangeability of judges embedded within the judiciary from the very start. Justices were able to cross the country and cross courts both as a way to provide knowledge and experience to the circuits, and as a way to gain knowledge and experience for their home Court. It is these two different strands that came together to produce modern-day visiting.

C. Bringing Visiting Judges to the Present

Visiting judges can be found throughout the federal courts today, but their contribution is felt most significantly in the courts of appeals. The courts that were born dependent upon the assistance of outside judges continue to rely on such help each year—more than the district courts to a considerable degree. All told, visiting judges sat with the appellate courts some 324 times between September 2016 and September 2017, and participated in 4,356 out of 54,347 decisions.[254] Within that set, they helped decide 1,916 out of 6,913 cases on the merits after oral argument—or nearly 30 percent.[255] (By contrast, the district courts received 205 visitors who terminated 3,464 out of 364,932 cases.[256])

Focusing on the courts where visitors make the most substantial contribution, the courts of appeals, it is worth noting that judges from all parts of the judiciary come to sit by designation. Specifically, district judges from in and outside the circuit, other circuit judges, and judges from Article III courts of “special” jurisdiction—the Federal Circuit and the U.S. Court of International Trade—all lend their services.[257] Representing the top tier, retired Associate Justice Sandra Day O’Connor routinely visited the courts of appeals after she left the Supreme Court, and retired Associate Justice David Souter has frequently visited the First Circuit since his departure from the Court.[258]

As to how the visiting arrangements are made, the apparatus established in the 1920s to govern the practice of visiting judges[259] is largely in place today. There are no roving judges, to be sure, but judges are consistently authorized to sit for reasons related to the disability of a judge or the workload demands of a court. And the process for administering these visits remains a bifurcated one.

Specifically, if help is sought from within a circuit, the chief circuit judge has the authority to make the assignment.[260] That discretion is not unconstrained, however. If the judge being drafted is an active judge, the chief judge of her district must consent.[261] If the drafted judge is senior, the judge herself must consent.[262] Notably absent from this scheme is the consent of an active judge being asked to visit. The origins of this omission can be found with Chief Justice Taft and Attorney General Daugherty. They were apparently able to convince House Committee members back in 1921 that with respect to the visiting arrangement for the district courts, “the matter of assignment to another district ought not to rest on the assent of the judge proposed to be transferred, . . . but . . . it should be the duty of such judge to accept the assignment.”[263] This notion carried over into the eventual bill,[264] and then later to the act extending the scheme to circuit courts.[265] The upshot of these different statutory provisions is that chief judges have robust authority when making intracircuit assignments.[266]

This process stands in marked contrast to the one for intercircuit assignments. If help is sought from outside a circuit, “a higher level of authority” is required beyond the consent of any chief judge: namely, the permission of the Chief Justice of the United States.[267] The chief judge of the would-be borrowing court must certify that assistance is needed and submit a request for aid to the Judicial Conference Committee on Intercircuit Assignments.[268] Consistent with Taft’s vision for a centrally administered judiciary, that committee in turn handles the arrangements of visits and submits the formal request to the Chief Justice.[269] Once again, if the judge being assigned is active, her chief judge must approve (along with the chief judge of the borrowing circuit).[270] And once again, if the judge being assigned is senior, she must consent to the assignment,[271] though no consent is needed if the judge is active.

There is one final complication when bringing in a foreign judge: intercircuit assignments must comport with the so-called “lender/borrower rule.”[272] The nonstatutory rule dates back to 1997, when it was approved by Chief Justice William Rehnquist, and states that “a circuit that lends active judges may not borrow from another circuit within the same time period of the assignment; a circuit that borrows active judges may not lend within the same period of the assignment.”[273] (Senior judges are exempt from this rule.[274])

The wisdom of such a rule seems self-evident given the official rationale for visiting judges—that it is a means of supporting overburdened courts.[275] That said, a former chief circuit judge suggested in an interview that the rule was adopted at least in part to limit potential abuses of the system (specifically, to reduce the incidents of judges taking visiting assignments as a means to “visit their grandkids” when the lending court was in arrears).[276]

Regardless of how the visitor is selected to come to court, once she is selected, the mechanics of the visit are functionally the same. Generally speaking, the visitor is assigned to a panel for a particular sitting, and may hear cases for a few days or as much as a week. True to the practice’s name, often the judge is physically “visiting”—meaning she is present at court for the sitting, though sometimes visitors join by videoconference. After hearing cases, the judge conferences with the other two (home) judges and is assigned particular opinions to author. She then returns to her own chambers, often continuing to correspond with the in-circuit judges as opinion drafts are circulated and any remaining matters are resolved.[277]

In sum, whether it is the chief judge or the Chief Justice who officially permits the arrangements, the federal courts of appeals today call on judges of all types. This Part has sought to provide a historical account of how this arrangement came to be. The next Part presents a detailed qualitative account of how it functions today.

II. The Current View from the Courts

With a sense of the lineage of visiting judges in place, one can turn to how the practice operates today and what its rationales are. While a review of the statutory framework for sitting by designation is a first step, it provides only an outline. Painting in the rest of the picture requires speaking with the judges and other judicial actors who administer, and experience, the practice throughout the year.[278]

This Part presents the findings of a multiyear qualitative study on the use of visiting judges in the federal courts. Specifically, it rests on thirty-five in-depth interviews with judges and senior members of the clerk’s offices of five of the courts of appeals, as well as with a former chair of the Judicial Conference Committee on Intercircuit Assignments. The findings provide an account of how sitting by designation functions on the ground, and also reveal several surprising aspects of the practice.

The necessity justification often invoked for visiting[279] came through in many of the judges’ and court administrators’ comments, but the same subjects were quick to note the practice’s limitations. Several of the judges in particular discussed how visitors could be overly deferential, and how they could not be expected to write opinions in significant cases, thereby shifting work back to the “home” judges.

More surprising was the discussion of a different rationale for having visitors: to train newly appointed district court judges. Though not one of the original reasons behind creating visiting arrangements in the first instance, nearly all of the courts surveyed here deliberately had new district judges come and sit for this purpose, wholly apart from workload concerns. In this way, the modern use of visiting judges appears to function not only for assistance, as originally envisioned, but also for the exchange of ideas among the judges themselves, thereby echoing the rationales for circuit riding.

A. Methodology

It has long been understood that qualitative methods, and especially interviewing, are often necessary to gather information about particular practices and institutions within the legal field.[280] As I have written about elsewhere, gathering data about court practices often requires interviewing the key actors who serve on, and administer, the courts, including judges and members of the clerk’s offices.[281] This form of data collection is essential where, as here, one seeks to gather information regarding a practice about which little public information is available, and in particular when one is seeking to learn what the subjects themselves think about the practice.

In the interest of performing an in-depth review, it was necessary to focus on a subset of the federal courts. As the use of visitors is most prevalent at the courts of appeals,[282] and as it is far more common for judges to visit “up” (meaning for district judges to sit by designation on the courts of appeals) than to visit “down,”[283] I focused on a number of the circuit courts. To facilitate in-depth, in-person interviews in particular, and consistent with past research,[284] I focused on a subset of the twelve regional circuit courts: the D.C., First, Second, Third, and Fourth Circuits.[285] To be clear, this is not a random sample of the courts and there are some commonalities among them. For example, they all encompass states that are in the Eastern part of the country and they are all relatively compact geographically[286]—factors that could ultimately affect visiting practices. That said, there are also key differences across the circuits that make them useful for study; for instance, as further discussed below, one circuit does not permit visitors, and the other four use them to varying degrees.

To select interview subjects, I conducted convenience sampling in some of the most heavily judge-populated areas within each circuit. Specifically, I contacted every judge in a given area by email and then met with those who were willing to do so.[287] For the D.C. Circuit, I contacted all active and senior judges in Washington, D.C. as of April 2012. Out of thirteen judges in this set,[288] I interviewed eight, as well as a senior member of the clerk’s office. For the First Circuit, I contacted all of the judges in Boston as of April 2012. Of the three judges in this set,[289] I interviewed one, as well as a senior member of the clerk’s office. In the Second Circuit, I contacted all of the judges in Manhattan, Brooklyn, New Haven, and Hartford between the spring of 2012 and the summer of 2013. Out of the twenty judges in this set,[290] I interviewed thirteen and a senior member of the clerk’s office. In the Third Circuit, I contacted all of the judges in Philadelphia between the spring of 2012 and the summer of 2013. Out of the four judges in this set,[291] I interviewed three and a senior member of the clerk’s office. Finally, in the Fourth Circuit, I contacted all of the judges in Baltimore, Alexandria, Raleigh, and Richmond as of June 2013. Out of the seven judges in this set,[292] I interviewed five and a senior member of the clerk’s office. To be clear, this is not a random sample of judges within each court. However, the judges I interviewed included a substantial mix along what are generally considered to be relevant dimensions: seniority, sex, and party of the appointing president. Furthermore, there was a substantial mix along dimensions most relevant to this study: judges who sat on courts with and without visitors, judges who had visited other circuits while on the bench, and judges who had previously been district judges who had sat by designation on the courts of appeals. Finally, for a study of this kind, there was wide participation of the judicial actors contacted; including all judges and members of the clerk’s office contacted, I had a participation rate of roughly 67 percent.

The majority of interviews were conducted in person (in chambers when I interviewed a judge, and in the clerk’s office when I interviewed a member of that office), although a few took place by telephone. A few interviews lasted only fifteen minutes, but most ran between half an hour and one hour. The interviews were all semi-structured; I asked each subject a set list of questions about the use of visiting judges in his or her circuit, although we also discussed topics that arose over the course of the interview[293] and further discussed matters related to another study I was conducting.[294] As a way to ensure that each subject was as candid as possible, I did not record the interviews and I assured each person I interviewed that I would not quote him or her by name.[295] This is why, consistent with past practice, I attribute my findings to “a judge” or “a senior member of the clerk’s office” within a given circuit.[296]

As with any study that relies on interviewing, this study is limited to the information provided by the subjects,[297] and it is possible that the subjects were not fully forthcoming or that their memories were imperfect. I tried to mitigate these possibilities by interviewing multiple subjects in each circuit and cross-checking information. Moreover, one can look to external indications of the subjects’ accuracy with respect to several of the study’s findings—and indeed, in Part III, I consider quantitative data on the courts’ panels, much of which is consistent with the accounts provided by the judges.[298] With this limitation in mind, the next Sections present the findings of the study, which provide an important window into how judges conceive of, and respond to, the practice of visiting judges today.

B. Assisting with Caseloads

As the historical account shows, the practice of visiting judges has been, officially, about necessity. Visitors are to be called upon when a judge is physically disabled or a court is struggling with a particularly large caseload. Indeed, Chief Justice Warren Burger suggested that the work of visiting judges had been crucial to the continued functioning of the appellate courts.[299] This view has been reflected in institutional planning for the federal judiciary, with both the Judicial Conference’s 1995 Long Range Plan for the Federal Courts[300] and 2010 Strategic Plan[301] stressing the workload contributions of visiting judges. It is therefore unsurprising that many of the subjects interviewed here emphasized how their use of visitors directly related to their caseload needs.

A senior member of the clerk’s office for the First Circuit began by noting that his Circuit’s use of visiting judges “depends on caseload and vacancies . . . [i]t’s really tied to need.”[302] A former chief judge of the same circuit explained how he determined how many visitors were needed in any given term: “When I was chief, the question was, was there a blank on the calendar? Does the projection need a space [for a visitor]?”[303] A judge for the Second Circuit stated that “right now we need visiting judges,” so the practice “is very important for us.”[304] Emphasizing the point, a former chief judge of the same circuit noted that while the court’s use of visitors “goes up and down,” historically visitors have been on “about forty percent of panels.”[305] A Third Circuit judge likewise said that the use of visitors on his court has “come and gone”—fluctuating depending on need.[306] A senior member of the clerk’s office for the Third Circuit said that when there were a significant number of vacancies on the court, “[w]e were having a hard time keeping our head above water” and relied on visitors more heavily.[307] Similar comments were made regarding the Fourth Circuit. As one Fourth Circuit judge put it, “[i]t’s about numbers,” specifically referring to how many judges are on the court at a given time and how many cases they expect to hear.[308] A senior court official similarly explained that the “use of visiting judges is affected by the mathematics” and is as simple as determining how many judges they have and, accordingly, how many are needed to round out the panels.[309]

Beyond relying on visitors to assist with the caseload in normal times, the members of the courts noted that it was particularly important to have additional help in times of judicial emergencies[310] or when all of the judges of a particular court were recused from a particular case. A former chief judge of the Second Circuit described how much his court had relied on visitors during a judicial emergency. He said that, to find sufficient help during this time, he “went through the district court alphabetically, and the Court of International Trade alphabetically” (noting with some humor that the judges at the end of the alphabet complained).[311] But, emphasizing how much his court required outside assistance, the judge said that, in addition to using his alphabetical process, he used the “mirror over the mouth” test: testing if the potential visitor was alive and, if so, drafting him or her.[312] Other judges reported visiting on other courts in times of mass recusal. Specifically, one Second Circuit judge reported sitting by designation on the Third Circuit at a time when all of the Third Circuit judges could not sit on a particular case.[313] A judge for the Fourth Circuit recalled sitting on the same panel for the Third Circuit (which was prompted by a wife of one of the judges having been a victim in a fraud scheme), and a separate appeal in the Third Circuit a year later.[314]