Amazon’s Quiet Overhaul of the Trademark System

Amazon’s dominance as a platform is widely documented. But one aspect of that dominance has not received sufficient attention—the Amazon Brand Registry’s sweeping influence on firm behavior, particularly in relation to the formal trademark system. Amazon’s Brand Registry serves as a shadow trademark system that dramatically affects businesses’ incentives to seek legal registration of their marks. The result has been a surge in the number of applications to register, which has swamped the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) and created delays for all applicants, even those that previously would have registered their marks. And the increased value of federal registration has drawn in bad actors who fraudulently register marks that are in use by others on the Amazon platform and use those registrations to extort the true owners.

Amazon’s policies also create incentives for businesses to adopt different kinds of marks. Specifically, businesses are more likely to claim descriptive or generic terms, advantageously in stylized form or with accompanying images, and to game the scope limitations that would ordinarily attend registration of those marks. And the same Amazon policies have given rise to the phenomenon of “nonsense marks,” which are strings of letters and numbers unrecognizable as words or symbols. In the midst of these systemic changes, Amazon has consolidated its own branding practices, focusing on a few core brands and expanding its use of those marks across a wide range of products. In combination, Amazon’s business model and Brand Registry have overhauled the American trademark system, and they have done so with very little public recognition of the consequences of Amazon’s business approach.

Amazon’s impact raises profound questions for trademark law and for law more generally. There have been powerful players before, and other situations in which private dispute resolution procedures have affected parties’ behavior. But Amazon’s effect on the legal system is unprecedented in scale and scope. What does—or should—it mean that one private party can so significantly affect a legal system? Do we want the trademark system to have to continually adapt to Amazon’s rules? If not, how can the law disable Amazon from having such a profound impact? In this regard, we explore the ways in which Amazon’s practices affect competition, harm the trademark system, and reshape how we think about trademark law at its foundation.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

Amazon’s dominance as a platform is widely documented.[1] Congress held hearings focused on Amazon for more than a year,[2] the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recently sued Amazon for unfair competition,[3] and scholars and commentators (including Amazon critic Lina Khan, Chair of the FTC during the Biden Administration) debate the effects of this dominance on consumer welfare.[4] But one aspect of that dominance has not received sufficient attention—the Amazon Brand Registry’s sweeping influence on firm behavior, particularly in relation to the formal trademark system. Amazon’s Brand Registry serves as a shadow trademark system[5] that dramatically affects businesses’ incentives to seek registration of their marks and to choose certain types of marks to designate their goods.

The Brand Registry is, most basically, a private dispute resolution system that allows mark owners to object to unauthorized uses of their marks on Amazon without having to file formal legal proceedings.[6] What makes Amazon’s system different than other private dispute resolution systems is the extent to which it influences parties’ behavior within the legal system itself.[7] The Brand Registry not only gives parties a cheaper and more efficient way to resolve disputes, but it also creates incentives for parties to use the trademark system differently than they otherwise would, and in ways that were not anticipated in the design of that system.

Most directly, the Brand Registry has changed the incentives to register trademarks. The American trademark system is use-based: Trademark rights arise out of use, not registration, and registration in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) simply records those rights and provides certain enforcement benefits.[8] But because unregistered marks have long been enforceable under federal law on largely the same terms as registered marks,[9] unregistered rights have often been perfectly adequate for many smaller businesses. Indeed, the availability of those unregistered rights has traditionally been seen as a benefit of the American system for small and medium-sized businesses.[10]

Amazon’s policies have shifted that calculus because parties can participate in the Brand Registry in the United States only if their mark is registered with the PTO—or, as of very recently, if their application to register is pending.[11] Given Amazon’s dominance as an online shopping platform, small and medium-sized businesses feel compelled to sell on the platform, and registration in the PTO is the ticket to the meaningful enforcement and search benefits provided to participants in the Brand Registry.[12] Businesses therefore have strong incentives to register marks when they previously would have relied on unregistered rights.[13]

The result has been a dramatic increase in the number of applications to register, which has swamped the PTO and created delays for all applicants, including those that would have previously registered their marks.[14] Our data show that annual PTO applications estimated to originate with small businesses have approximately doubled since Amazon’s Brand Registry began, from about one hundred thousand to two hundred thousand, increasing the proportion of filings from these entities from about 30 percent to about 40 percent annually.[15] In response to the delays that Amazon’s policies helped create, Amazon has recently started qualifying parties for the Brand Registry based only on a pending application.[16] This change enables parties to privately enforce marks that might ultimately be rejected by the PTO and is likely to increase applications even more, creating further PTO delays.

By conditioning participation in the Brand Registry on PTO registration or at least an application to register, Amazon has created opportunities for pirates to extort sellers that operate on the platform using unregistered marks.[17] Like old-fashioned cybersquatters, these bad actors apply to register the unregistered marks in their own names and then seek to extort the true owners of those marks by threatening the owners with exclusion from Amazon’s platform.

Not only does the Brand Registry increase incentives to register marks for which the owners would previously have relied on unregistered rights, but it also creates incentives for businesses to adopt different kinds of marks. Descriptive terms (like NATIONAL CAR RENTAL for nationwide car rental services) and generic terms (such as APPLE for apples) are especially more valuable in light of Amazon’s policies.[18] Descriptive words are normally not protectable or registrable without evidence that consumers actually associate the term with a single source (what trademark law calls “secondary meaning”), and this additional proof requirement is supposed to be a deterrent to claiming descriptive terms.[19] Generic terms are categorically excluded from protection, even if they have secondary meaning.[20] Despite these rules, there has always been some incentive to claim descriptive and generic terms as trademarks because control over those terms can provide meaningful competitive benefits.[21] But with Amazon, there is an overwhelming incentive to control descriptive or generic terms because consumers often use those terms to search on Amazon.

The Brand Registry’s structure also enables parties to game the trademark registration system and effectively get the full benefits of exclusive rights in descriptive and maybe even generic terms.[22] Of particular relevance, parties can avoid descriptiveness and genericness rejections in the PTO by applying to register those terms in a stylized format (such as a particular font) or with an accompanying image, sometimes disclaiming rights in the descriptive or generic word(s) themselves. In those cases, trademark law supposedly limits the scope of rights accorded to the registered mark to reflect the stylization or accompanying image.[23] But while Amazon is capable of considering the format in which a mark is presented, it does not require visual matching: A simple text match is sufficient to trigger exclusion.[24] That means a highly descriptive term, and maybe even a generic one, might be deemed registrable in the PTO because of its stylization but then enforced on Amazon as if it were a registration of the unprotectable word itself. That gaming disrupts the balance that the formal legal system tries to strike between recognition of the source-identifying capacity of design features on the one hand and the need for competitive access to descriptive and generic terms on the other, ignoring the reasons why those marks get any protection at all.[25]

The Brand Registry also creates greater incentive to claim so-called “nonsense marks,” which are strings of letters or numbers that are not comprehensible as words. For example, ELXXROONM, SUJIOWJNP, XUFFBV, and LXCJZY are all nonsense marks parties have recently applied to register in the PTO.[26] Indeed, the PTO data suggest a tremendous increase in filings for nonsense marks in the past few years, from almost none to over twenty thousand applications annually (0.5 percent of annual filings to approximately 4.5 percent).[27]

Nonsense marks are currently easy to register as trademarks because they appear not to provide any information about the goods or services with which they are used, making them inherently distinctive and thus immediately protectable.[28] But those “marks” pose significant conceptual problems for trademark law, which presumes that parties are claiming terms that will have some meaning to consumers.[29] That is a sensible assumption in a world where consumers search and buy by brand. But when algorithms do the searching, businesses just need something that the algorithm can use to preference them. Nonsense will do.[30]

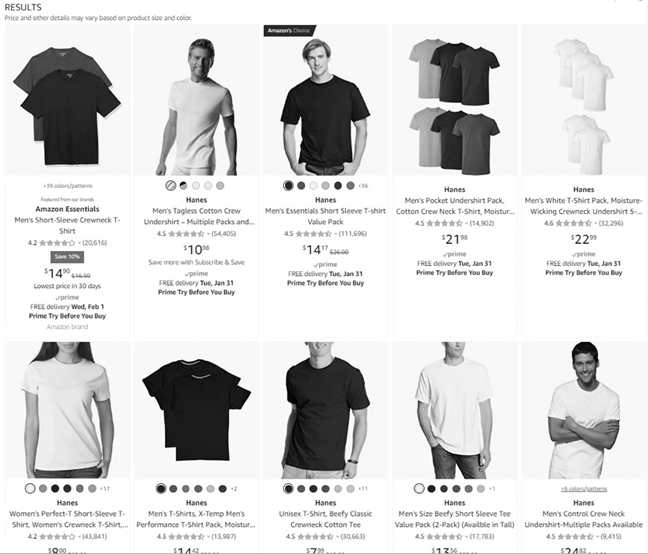

Critics of excessive branding might rejoice about that de-centering and potential democratization of the online marketplace. But there is irony here: Amazon’s de-centering third-party branding will likely amplify Amazon’s own power by making its search function and algorithm even more important in finding products. And it certainly enhances the value of Amazon’s own branding strategies, as reflected in the massive expansion of products sold under the Amazon Basics and Amazon Essentials brands.[31] Amazon controls the platform and can preference its own products in search results based on product descriptor keywords, making its house brand more important than product line brands. To take just one example, a search for “Hanes T-shirt” returns an Amazon Essentials T-shirt as the first result, followed by several Hanes results.[32]

In all of these ways, actors affected by Amazon’s business model and Brand Registry have overhauled central aspects of the trademark system in ways that are potentially troublesome. The Brand Registry has increased incentives to register and to register different types of marks, putting pressure on several substantive validity doctrines and forcing the PTO to deal with a huge influx of applications that examiners cannot manage in a timely way. Moreover, this legal overhaul has happened with very little public recognition of the consequences of Amazon’s business approach.[33]

We do not claim that Amazon specifically intended to affect the trademark system in any of the ways we describe or even that Amazon has fully understood the extent of its impact. It seems very likely that Amazon adopted policies that it thought were sensible for its business and that it created the Brand Registry in part to address actual concerns about counterfeit goods and product liability—and, not incidentally, to avoid regulation like it would face under Congress’s proposed SHOP SAFE Act.[34] In that regard, it may be that Amazon’s policies and practices have simply had the unintended, though not necessarily unforeseeable, consequences that we describe.

Regardless of Amazon’s intent, its business model and Brand Registry raise profound questions for trademark law and law more generally. Amazon is not the first commercial powerhouse, nor is it the first to create a private dispute resolution system. But Amazon’s effect on the trademark system is unprecedented. One set of questions is institutional and structural. What does, or should, it mean that one private party can so significantly affect a legal system? Do we want the legal system to have to continually adapt to Amazon’s rules? If not, how can the law disable Amazon from having such a profound impact?

Another set of questions focuses more specifically on the overall effects of Amazon’s policies on competition and on trademark law’s normative commitments. As we describe, Amazon’s model and its policies likely increase its own power vis-à-vis third-party brands, de-centering branding more generally. The net value of that shift may be in the eye of the beholder: It depends on how one weighs the potential benefits of search simplification and lower prices for consumers, as well as the ease of marketplace entry for third-party sellers, against the costs of Amazon’s increased power over third-party sellers. Likewise, the benefits of a reduction in the power of brands depend on whether alternative search tools, particularly algorithms that focus on product information and consumer reviews, convey relevant information to consumers as effectively as trademarks. In the end, whether and how we should respond to Amazon’s effects on the trademark system depends on whether we want the trademark system to demand that trademarks play their traditional role or whether instead the facts on the ground have changed so much that the premises of that system no longer hold.

Many legal scholars have considered whether and how law might have to adjust to new platforms, asking, among other things, whether Uber drivers should be treated as employees and how to assess trademark liability for platforms.[35] These scholars, as exemplified by Julie Cohen, recognize that the platform is “the core organizational form of the emerging informational economy” and has replaced the more traditional marketplace as the locus for barter and exchange.[36] We extend this literature by demonstrating how a dominant platform like Amazon can spearhead an overhaul of a legal system, at least with the assistance of its third-party sellers.[37]

Part I describes the conventional trademark system’s aim and design. Part II turns to Amazon’s business model and Brand Registry. Part III builds on these two parts by investigating how Amazon’s practices have provoked the businesses selling wares there to change how they think about registering marks and the marks they choose, plus the trademark extortionists that have arisen in response to this ecosystem. Part IV considers whether potential precursors like Sears and Network Solutions provide useful analogies and concludes that Amazon’s impact on the trademark system is unprecedented. That Part then discusses possible changes to PTO practice and Amazon policies that would address Amazon’s impact. Finally, it considers the broader impact of Amazon’s practices on trademark law and competition more broadly.

I. The Conventional Trademark System

Scholars have long debated whose interests trademark law primarily serves. On one account, trademark law aims to protect businesses against illegitimate uses of their marks that would divert customers or confuse consumers about those businesses’ relationship to the goods bearing their marks.[38] Other accounts, particularly in modern commentary, make consumer interests primary. Trademark law makes misleading uses of trademarks actionable so that consumers are not defrauded and can rely on marks to select goods from the sellers they wish to patronize.[39]

Courts often present business and consumer interests as harmonious, so that trademark protection simultaneously advances both. As the Supreme Court has stated,

[T]rademark law, by preventing others from copying a source-identifying mark, “reduce[s] the customer’s costs of shopping and making purchasing decisions” . . . for it quickly and easily assures a potential customer that this item—the item with this mark—is made by the same producer as other similarly marked items that he or she liked (or disliked) in the past. At the same time, the law helps assure a producer that it (and not an imitating competitor) will reap the financial, reputation-related rewards associated with a desirable product.[40]

But regardless of how one prioritizes the respective interests, source indication is the conceptual center of every serious theoretical justification of trademark law. All of the benefits of trademark protection depend on a mark’s capacity to identify goods or services as emanating from a single source, and all of the harms trademark law targets result from interference with that source-indicating function.

Given that focus on source indication, it is no surprise that modern doctrine defines trademark subject matter fundamentally in terms of capacity to indicate source. According to the Lanham Act, a trademark is “any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof” that is used “to identify and distinguish his or her goods . . . from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods.”[41] Because “human beings might use as a ‘symbol’ or ‘device’ almost anything at all that is capable of carrying meaning,” as the Supreme Court noted, trademark subject matter is broad and capacious, including colors, product packaging, and even the design of products, to the extent they identify source.[42]

The following sections elaborate, respectively, on trademark’s distinctiveness requirement, the requirement of trademark use, and the registration process of the trademark system.

A. The Distinctiveness Requirement

Trademark law calls source designation “distinctiveness,” and that concept is the foundation of protectability.[43] Consumers are unlikely to be confused about the source of a product or service if they do not recognize a particular designation as source-indicating in the first place.[44] Relatedly, consumers are only able to use marks to reduce their search costs—the costs of identifying goods or services with the characteristics they want—if those marks reliably indicate who is responsible for the goods or services they are used with.[45] Moreover, from a business’s perspective, if consumers know that a term or symbol identifies the business as the source of goods or services, the business will be encouraged to invest in the consistent quality of its goods or services, an important goal of trademark law.[46] In addition to the benefits of requiring distinctiveness, there is a cost to granting trademark rights to words or symbols that do not identify source. The principal worry is that protecting those words or symbols would inefficiently prevent other businesses from using them in competitively useful ways.[47]

The framework to assess distinctiveness and thus protectability in trademark law is set out most famously in Abercrombie & Fitch Co. v. Hunting World, Inc., a 1976 Second Circuit decision authored by Judge Friendly[48] that was widely relied upon by other courts, including the Supreme Court.[49] Abercrombie identified five different categories of terms with respect to trademark protection: “Arrayed in an ascending order which roughly reflects their eligibility to trademark status and the degree of protection accorded, these classes are (1) generic, (2) descriptive, (3) suggestive, and (4) arbitrary or [(5)] fanciful.”[50] As explained by the Second Circuit, a term is categorized based on the amount of information it supplies about the goods or services with which the term is being used.[51]

As per Abercrombie, a “generic” term “refers, or has come to be understood as referring, to the genus of which the particular product is a species.”[52] For example, IVORY would be generic for products made from elephant tusks, but not for soap products.[53] Generic terms are never protectable as trademarks, even if they develop secondary meaning.[54] As courts routinely say, competitors should have the absolute right to call their goods or services by their category name; if they could not, they would be unable to compete effectively and consumers would ultimately be hurt by confusion and illegitimate restriction of competition.[55]

“Descriptive” terms are presumptively unprotectable, but they can earn their way into trademark status. As the Second Circuit has explained, a descriptive term “describe[s] a product or its attributes.”[56] These are terms like HOLIDAY INN for inns in which people stay while on holiday, ALL BRAN for all-bran cereal, and AMERICAN GIRL for American girl dolls.[57] To the Seventh Circuit, “[a] descriptive mark is not a complete description, . . . but it picks out a product characteristic that figures prominently in the consumer’s decision whether to buy the product or service in question.”[58] Similar to generic terms, the fear with protecting descriptive marks is that competitors might want to use a term because it describes their product too, and those competitors would be unfairly disadvantaged if one business in the competitive landscape has exclusive rights in such a term.[59]

Descriptive terms are not inherently distinctive because they give direct information about the nature or characteristics of the goods or services they are used with and therefore do not automatically signify source.[60] Only when consumers have to come to understand a descriptive term primarily as a source indicator, and not just as a descriptor of the products or services, can it be protected as a trademark.[61] The upshot of that rule is that descriptive terms cannot be protected immediately upon use; it takes time (and usually substantial advertising) for them to become trademarks.[62] As Judge Friendly explained in Abercrombie, in allowing protection for descriptive marks that have acquired secondary meaning, trademark law “strikes the balance . . . between the hardships to a competitor in hampering the use of an appropriate word and those to the owner who, having invested money and energy to endow a word with the good will adhering to his enterprise, would be deprived of the fruits of his efforts.”[63]

Even when descriptive terms develop secondary meaning, trademark law recognizes that competitors might still need to use the terms in their primary, descriptive sense. The descriptive fair use defense permits a business to use a competitor’s protected descriptive mark, not as a mark, but “fairly and in good faith only to describe the [business’s] goods or services.”[64] For example, if Delta Airlines described itself patriotically as “an American airline,” that might be permissible as a descriptive fair use of the AMERICAN AIRLINES mark, as long as Delta was using “American” in a non-trademark way. The defense is an important one,[65] but it is relatively narrow because it does not allow others to use the term as a mark—including a domain name or slogan—even if that term also describes the defendant’s goods or services.[66] Lisa Ramsey documents that the defense is murky, and “[r]elevant factors for determining whether a use is a trademark or descriptive use include the size, style, location, and prominence of the descriptive term in comparison to the defendant’s use of its own trademark or other descriptive matter in advertising or product packaging.”[67]

“Suggestive,” “arbitrary,” and “fanciful” terms are considered inherently distinctive and therefore protectable without proof of secondary meaning.[68] As explained by the Fifth Circuit, a “suggestive” term “suggests, rather than describes, some particular characteristic of the goods or services to which it applies and requires the consumer to exercise the imagination in order to draw a conclusion as to the nature of the goods and services.”[69] For example, courts have found SWAP for a watch with interchangeable parts,[70] 5 HR ENERGY for an energy drink,[71] and GLASS DOCTOR for glass installation and repair services all to be suggestive.[72] “Arbitrary” terms are preexisting words that are used in “an unfamiliar way” that is conceptually unrelated to the category of goods or services at hand.[73] Examples of marks courts have classified as arbitrary are STARBUCKS for coffee,[74] VEUVE (meaning “widow” in French) for champagne,[75] and KIRBY for vacuum cleaners.[76] “Fanciful” terms are “invented solely for their use as trademarks.”[77] Courts have deemed fanciful marks to include CARSONITE for highway markers[78] and LUMAR for fabric softener.[79] Suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful terms are immediately protectable because they do not provide any direct information about the goods or services and are therefore assumed automatically to convey source information. Protection of those terms also does not “depriv[e] others of a means of describing their products to the market.”[80]

Thus, a claimed mark’s protectability depends on its distinctiveness, which is determined according to Abercrombie’s classification scheme. As discussed in the next Section, a claimed mark’s protectability also depends on the way the claimant uses the purported mark.

B. The Use Requirement

Eligibility for trademark status depends not only on a sign’s capacity to identify source, but also on evidence that the claimant has actually used that sign in a particular trademark way.[81] “Use” in this sense has special meaning: It has a quantitative dimension (some, rather than none), and it also connotes particular functional characteristics, namely that the sign as used has the effect of identifying source.[82] As the Supreme Court recently explained, a trademark “identifies a product’s source (this is a Nike) and distinguishes that source from others (not any other sneaker brand).”[83] Indeed, to the Court, “whatever else it may do, a trademark is not a trademark unless it” performs this source-identifying function, “tell[ing] the public who is responsible for a product.”[84]

It is easy enough to state the principle that a sign must be used as a trademark to qualify for protection; it is much harder in practice to say what that means. In theory, the ultimate issue is whether consumers regard the mark as used as identifying source, which suggests that trademark use is an empirical question.[85] But because it is often impractical to assess consumer understanding directly, courts have long used proxies to make that judgment, focusing on the prominence and location of a use; the consistency of presentation of the sign, stylization, and coloration; and the presence or absence of other identifying signs.[86] In one recent case, for example, the court concluded that Jaymo’s use of “S’Awesome” for food sauces, as shown in Figure 1, was not trademark use.[87] The court explained that despite the consistency of Jaymo’s use, “S’Awesome blend[ed] into a smattering of text on the label style used on most of Jaymo’s sauces,” and that “placement and emphasis on other terms coupled with the comparatively small, plain font of the term fail[ed] to adequately demonstrate it [was] being used as a source indicator on the bottle labels.”[88]

Figure 1. Jaymo’s food sauces

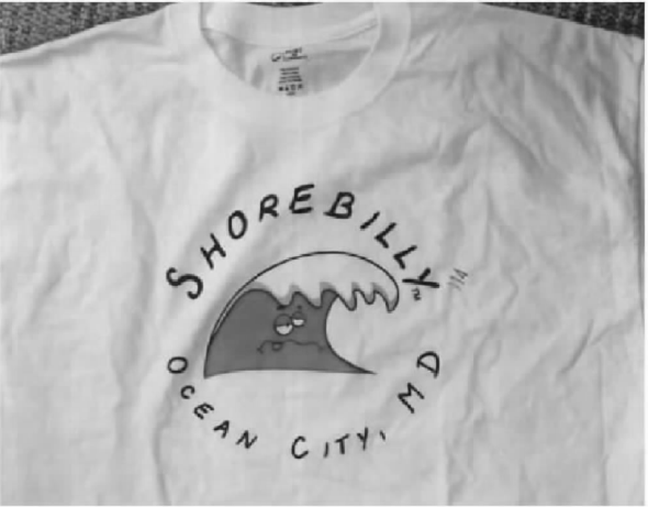

The PTO considers whether a sign functions as a mark when considering a claimed mark’s registrability. In that context, the rule operates in the negative. A claimed mark is not registrable when it fails to function as a mark. The PTO’s Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure describes a purported mark’s failure to function primarily by reference to other functions performed by the claimed matter. A claimed mark might fail to function as a mark, for example, “because it is merely ornamentation,”[89] it constitutes “informational matter,”[90] or is a “model or grade designation.”[91] Especially when evaluating whether a claimed mark is merely ornamentation, the Trademark Office puts significant weight on the location of the claimed mark, as shown in the specimen filed with the PTO showing the mark’s use, presuming that signs in “trademark spaces” function as marks.[92] To illustrate, the PTO rejected an application to register the “Shorebilly” word and design mark shown in Figure 2 when the applicant submitted a specimen showing use of that claimed mark in large format in the center of a T-shirt.[93]

Figure 2. Shorebilly and design on T-shirt

But the applicant was able to register that same mark when he submitted a substitute specimen using the mark, as shown in Figure 3, “in the Polo and Izod fashion that the examiner had told him was illustrative of a proper trademark use.”[94]

Figure 3. Revised T-shirt design

In sum, while the principle that a sign must be used as a trademark to qualify for protection is straightforward in theory, its application often hinges on nuanced and context-specific factors, such as presentation, placement, and consumer perception. This complexity underscores the pivotal role of both judicial proxies and PTO guidelines in evaluating whether a claimed mark functions as a source identifier, setting the stage for further exploration of the trademark registration process.

C. The Trademark Registration Process

Signs that satisfy trademark law’s legal requirements, including distinctiveness and use as a mark, are eligible to be registered with the PTO.[95] But registration is not central to American trademark law, or at least historically it has not been.[96] Unlike most other countries in the world, trademark rights in the United States arise through use rather than registration,[97] and unregistered marks are enforceable under federal law on substantially the same terms as registered marks.[98]

That is not to say that registration is irrelevant; indeed, registration has several important legal benefits. For one thing, registration confers nationwide priority as of the date of application, subject to uses that predate the registrant’s use or application to register.[99] Unregistered marks, by contrast, are protected only in the geographic areas in which they were in use prior to the allegedly infringing use.[100] Registered marks are also presumed valid and owned by the registrant,[101] and certain of those presumptions become irrebuttable if the registration becomes incontestable.[102] Moreover, registered marks are subject to customs enforcement,[103] and some enhanced remedies are only available for registered marks.[104] Under the Lanham Act, then, registration serves as a carrot rather than a stick.

Some of the legal incentives to register are more significant for certain types of businesses. There are meaningful incentives to register for businesses that anticipate significant geographic expansion, as nationwide constructive use effectively secures rights across the country, even in advance of actual use in many places.[105] Incontestability is particularly valuable for marks—like descriptive terms, geographic terms, surnames, and product design—that owe their existence to secondary meaning,[106] because marks that are incontestably registered cannot be challenged for lack of secondary meaning.[107] Customs enforcement is valuable for parties that sell on a scale that is likely to attract widespread copying. And registration can be extremely helpful for parties with international aspirations because various treaty provisions make it easier to secure foreign trademark rights when a party has registered in the United States.[108]

Beyond these legal encouragements, practical considerations also might counsel in favor of registration. Registered marks are more easily findable, particularly in the PTO’s publicly-available database, and public notice of claims to those registered marks helps avoid conflict to the extent it prompts others to avoid using similar marks.[109] Registration also enables the PTO to refuse third-party trademark applications for confusingly-similar marks.[110]

At the same time, there are also advantages to unregistered rights. Most obviously, unregistered rights are free: The rights attach naturally as soon as the party starts using the mark to indicate the source of its goods. That means that less-resourced parties can develop rights without having to spend time or money filing trademark applications.[111] Registration favors large, sophisticated companies, which generally are familiar with the registration system and have the resources to seek registration of each new potential trademark.[112] Given the lack of expense associated with unregistered rights and the ability to enforce those rights under federal law on substantially the same terms as applicable to registered marks, unregistered rights are perfectly adequate, and may be superior, for many trademark owners.[113] Even sophisticated parties might have reason to prefer unregistered rights for marks that are less likely to be durable branding elements over time. A party that goes to the expense of registering a mark has some incentive to stick with that mark over longer periods of time, whereas unregistered rights are better suited to marks that might be adapted or used in connection with different goods or services in the future.[114]

Trademark registration, while historically secondary to the use-based foundation of American trademark law, offers meaningful legal and practical advantages that make it a valuable tool for many businesses. However, the cost and complexity of registration often favor larger, resource-rich entities, leaving unregistered rights as a viable and often preferred option for smaller or more flexible businesses. With this understanding of trademark law’s framework, we now shift focus to Amazon’s business model and its Brand Registry.

II. Amazon’s Business Model and Brand Registry

Since Amazon launched, it has not only grown what is perhaps the most vibrant online commerce platform, with 9.7 million third-party businesses selling goods on Amazon,[115] but it has also created a brand that is valued at over $576.6 billion.[116] To better understand how Amazon’s business practices have upended central aspects of the conventional trademark system, we must first examine how Amazon has achieved such market dominance. Part II.A provides background on Amazon’s business model and its evolution, and Part II.B turns to Amazon’s Brand Registry and its role in Amazon’s business model.

A. Amazon’s Business Model and Evolution

Amazon was founded in 1995 as an online bookseller, and it has since evolved into a pervasive e-commerce platform and then some.[117] Indeed, a recent in-depth cultural study of Amazon describes it as the most ubiquitous company in history: “the ‘everything’ brand for ‘everyone.’”[118] It is the biggest online retailer in the United States, controlling an estimated half of online retail sales.[119] And its reach is global: Amazon serves customers in nearly two hundred countries.[120]

From the start, Amazon has had grand ambitions, as evidenced by early marketing materials drawing on its trademark:[121] “Amazon.com’s name pays homage to the Amazon River. Just as the Amazon River is more than six times the size of the next largest river in the world, Amazon.com’s catalog is more than six times the size of the largest conventional bookstore.”[122] Even with these aspirations, founder Jeff Bezos always intended for Amazon to be much more than the largest online bookstore. He began selling books only after considering twenty product categories, with the books as the entry point to, as communications scholar Emily West puts it, ultimately “build[ing] a mammoth e[-]commerce website.”[123] According to Bezos himself, “we’re not trying to be a book company or trying to be a music company—we’re trying to be a customer company.”[124]

Amazon’s business strategies have generally been in service of this overarching goal of attracting loyal customers and distributing to them, rather than just selling books. In particular, Amazon has sold books and other products at very low prices as loss leaders to attract customers, which has also led to accusations of predatory pricing.[125] In doing so, Amazon has demonstrated its willingness to delay profits to build up its customer base, all the while drawing consumers away from its competitors.[126] Indeed, Amazon only became consistently profitable in 2015.[127] More generally, especially in its early years, Amazon did not spend much on traditional advertising and marketing but instead spent its money improving the platform’s customer experience, including its unprecedented fast, free shipping that ultimately became the central feature of its popular Prime membership service.[128]

To broaden its product base and attract yet more customers, since 1999 Amazon has allowed third parties to sell their products on the Amazon platform.[129] Amazon now has almost ten million third-party sellers on its platform,[130] which has created network effects to lure consumers, which in turn attracts more sellers, ad infinitum.[131] Amazon’s offering of one-click ordering (and the resulting patent it obtained on it) typifies how the platform has sought to provide extreme convenience for consumers.[132]

Since its launch, Amazon has sought to gain consumer trust by collecting and sharing consumer reviews of the products it sells. Initially, competitors and experts scoffed at that practice, believing it would be counterproductive because consumers would at least sometimes leave bad reviews.[133] But Amazon seems to have won that bet: Its collection of reviews, one of the world’s largest, has fostered a “reputation economy” and propelled Amazon’s market dominance.[134] Amazon also collects reams of data about consumer behavior in service of developing its predictive models.[135] It uses these models to continually adapt its platform and product offerings, which encourages consumers to keep using Amazon.[136]

All of these strategies are reflected in the logo that Amazon redesigned in 2000.[137]

Figure 4. Amazon’s logo, redesigned in 2000

The logo has an arrow going from the ‘a’ to ‘z’ in AMAZON, to suggest that all products from A–Z can be found and bought on the platform.[138] And the arrow also suggests that Amazon brings products from all locations and sellers to consumers’ homes.[139]

As a result of these unique strategies and practices, Amazon’s business model has been a smashing success.[140] After Walmart, Amazon is the second largest retailer in the United States, with $355.1 billion in sales in 2023.[141] And it is by far the largest online retailer in the United States, controlling about half of the online retail market.[142]

Third-party sales have become a critical part of Amazon’s business model. Indeed, the money Amazon makes from charging third parties to use its platform, such as listing fees, represented 23 percent of Amazon’s revenues in 2022 ($117.7 billion), second only to the 43 percent of Amazon’s revenues generated in first-party sales that year ($220 billion).[143] As important as the third-party sellers are to Amazon, Amazon is even more essential to the third-party sellers. As one seller pointed out, “If you say no to Amazon, you’re closing the door on tons of sales.”[144]

Amazon’s market dominance is also reflected in the great degree of public confidence in Amazon. Amazon is at or near the top of the list of most-loved brands in the United States.[145] In fact, one recent poll done by Georgetown University found that Americans trust Amazon more than any institution except the military, ranking the company above all other parts of the U.S. government and above universities, non-profit institutions, and major businesses.[146] And Amazon is also one of the world’s most market-capitalized companies.[147]

With this exploration of Amazon’s business model generally, we now turn to how Amazon has deployed its Brand Registry to advance its business goals.

B. The Brand Registry as a Business Tool

As Amazon sought to advance its overall business model, it encountered concerns from the third-party sellers and consumers (both of which were essential to attract to and keep on its platform), as well as from the government. Third-party sellers—both potential and actual—wanted Amazon to do more to prevent counterfeit versions of their goods from appearing on its platform.[148] Those sellers expressed unwillingness to sell their genuine goods on Amazon unless Amazon took further action to exclude counterfeits.[149] And consumers were unhappy when they accidentally purchased knockoffs instead of the genuine goods they were trying to buy.[150] As complaints mounted, Congress held hearings on counterfeit goods being sold on online platforms like Amazon.[151] Several legislators introduced the SHOP SAFE Act, which would make online platforms “liable for infringement of a registered trademark by a third-party seller of goods that implicate health and safety unless the platform takes certain actions.”[152]

Sellers’ and consumers’ anxiety about Amazon’s platform, and the looming threat of regulation, posed real threats to Amazon’s market dominance.[153] In response, Amazon launched the first version of its Brand Registry in 2015.[154] That fairly limited program allowed businesses to better control their own listings and to contest other listings on copyright grounds.[155] Yet the filing process under that program was time-consuming and cumbersome,[156] and the program did little to address counterfeit goods, which are principally targeted through trademark claims, not copyright claims.[157]

In 2017, Amazon launched the second version of its Brand Registry. In addition to providing enhanced branding capabilities for businesses’ own listings, the new Registry made it easier to remove listings of counterfeit goods.[158] Businesses could qualify for the Brand Registry in the United States if they had registered their trademark on the Principal Register of the PTO and were using that mark on their products or packaging.[159] Only trademarks that contain alphanumeric characters can be listed in the Brand Registry, though the marks can also be stylized or include an image.[160] The word(s) in the trademark must identically match the spelling, spacing, and punctuation found in the U.S. trademark registration.[161]

With the launch of the second version of the Brand Registry, Amazon put in place a three-hundred-person customer service team dedicated to addressing reports of trademark and copyright infringement from Brand Registry members.[162] Amazon now promises round-the-clock service to address these reports, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.[163] Rather than taking days to address such seller claims, the team would resolve these claims within a few hours and without a court order.[164] The Brand Registry made it easier for registered businesses to identify potential infringements by providing search tools, including reverse-image search technology, to help locate other products using the same name or packaging as the registrant.[165] And the Registry enables mark owners to benefit from predictive protections that block improper listings from third parties in the first place.[166] The Brand Registry has also been attractive to third-party sellers because it offers them higher visibility in consumer search results on Amazon, brand analytic tools, and the ability to give one’s products to credible buyers for Amazon reviews.[167]

In 2019, Amazon made it even easier for sellers to protect their brands and qualify for the Brand Registry by launching the Intellectual Property Accelerator, which is a curated network of intellectual property law firms providing trademark registration services at pre-negotiated rates.[168] Amazon explained that it “created [the] Accelerator specifically with small and medium businesses in mind,” so as to help them “more quickly obtain intellectual property . . . rights and brand protection in Amazon’s stores.”[169] Businesses participating in the Accelerator get charged only by the law firm they are using, not Amazon.[170]

Businesses that use the Accelerator program get “accelerated access to brand protection” on Amazon.[171] Rather than having to wait for their trademark registration to issue, Amazon provides Accelerator participants access to the Brand Registry as soon as they have filed a trademark application with the PTO.[172] Amazon says that it provides that early access because “the participating law firms have been thoroughly vetted,” and the marks Accelerator participants apply to register will therefore “be strong candidates for registration.”[173] Though Amazon does not make public all of the specific Brand Registry benefits that it provides on this accelerated basis, it has indicated that Accelerator participants get “automated brand protections, which proactively block bad listings from Amazon’s stores, increased authority over product data in our store, and access to our Report a Violation tool, a powerful tool to search for and report bad listings that have made it past our automated protections.”[174]

More recently, as of approximately 2023, Amazon made all sellers, not just those using the Accelerator program, eligible for its Brand Registry as soon as they have a pending application to register a trademark with the PTO.[175] Amazon has not publicly explained its reasons for that expanded eligibility, but it certainly calls into question the previous claim that Accelerator participants warranted early access because the marks they applied to register were particularly likely to be registered.[176]

The new and improved Brand Registry has been a hit among third-party sellers. In 2021, there were more than seven hundred thousand active marks enrolled in the Brand Registry worldwide, a 40 percent increase over the previous year.[177] In 2022, more than sixteen thousand trademarks were the subject of the Accelerator program.[178] Amazon advertises the successes of the Brand Registry and the Accelerator program in promoting its participants and removing infringing listings.[179] For example, Amazon boasts that it has blocked or removed 99 percent of listings suspected of offering counterfeit goods.[180] The growth and success of the Brand Registry have been noticed by businesses and business writers, who have written about the obvious advantages to being part of the Brand Registry.[181]

Despite the general success of the Brand Registry from the perspective of many, some larger companies like Nike have not been as impressed with Amazon’s anti-counterfeiting measures.[182] Nike began selling on Amazon only after Amazon created the Brand Registry, believing the Registry would help stop counterfeiting. But Nike later reversed course and stopped selling directly on the platform because it thought Amazon was still not sufficiently controlling counterfeit sales.[183] Not many companies can afford to take that position. According to Emily West, “Nike had confidence in the power of its brand to leave Amazon, but as one industry analyst put it, ‘I don’t think as many brands can be as selective as Nike.’”[184] Because most sellers do not have Nike’s power and need to sell on Amazon, the Brand Registry is essential for them.

All in all, Amazon’s Brand Registry undergirds the platform’s business model by helping to keep the vast majority of third-party businesses comfortable and motivated to sell their wares on Amazon, which in turn keeps customers hooked on the platform. The Registry does so by making it easier for registrants to have infringing sellers removed from the site expeditiously, and by giving registrants superior search optimization tools. The resulting seller and consumer satisfaction removes some of the ongoing pressures for the government to regulate Amazon in this regard, such as through the SHOP SAFE Act, which would expose Amazon to significantly greater liability for selling counterfeit goods.[185]

III. Amazon’s Overhaul of the Trademark System

Third-party sellers’ widespread participation in Amazon’s Brand Registry has not only promoted Amazon’s business model. As this Part addresses, it has also put significant hydraulic pressure on the U.S. trademark system, in effect overhauling the system and calling into question many of trademark law’s foundational assumptions.[186] Because Amazon’s Brand Registry is built on the U.S. trademark registration system—as opposed to being a system entirely of Amazon’s creation—businesses have developed very different practices with regard to the selection and registration of trademarks. In this Part, we detail some of the most significant of these changed practices: small businesses’ increased use of the trademark register, trademark extortion, registration of descriptive and generic marks, and registration of nonsense marks. We also discuss how Amazon’s use of its own internal house brands fits into this story. These changes have happened relatively quietly without much public attention, but they have materially overhauled the trademark system.

Even though Amazon’s Brand Registry might be seen as a shadow trademark system, the story here is not one about a community that relies primarily on norms rather than formal legal rules, such as those described by other legal scholars focusing on the fashion industry, cuisine, stand-up comedy, roller derby, tattoos, or magic.[187] Those situations are often described as involving “intellectual production without intellectual property” (or “IP without IP”) or a “negative space.”[188] Amazon’s Brand Registry is different because it influences parties’ use of the formal trademark system. Indeed, the story here is more like “IP plus IP” or an “exponential space.”

A. Small Businesses’ Approach to PTO Registration

As noted above, American trademark law has long protected unregistered marks on largely the same terms as registered marks, making registration a set of advantages rather than a requirement.[189] For many small and medium-sized businesses, those advantages were not significant enough to justify the time and expense of registration, which means that registration has traditionally been more the province of larger, established companies.

Amazon is changing that dynamic. Because the Brand Registry requires PTO registration, or now at least a pending application to register,[190] the incentives for small and medium-sized businesses selling on Amazon are very different. Because most smaller businesses want to be in the Brand Registry, they are much more likely to register than they once were.[191]

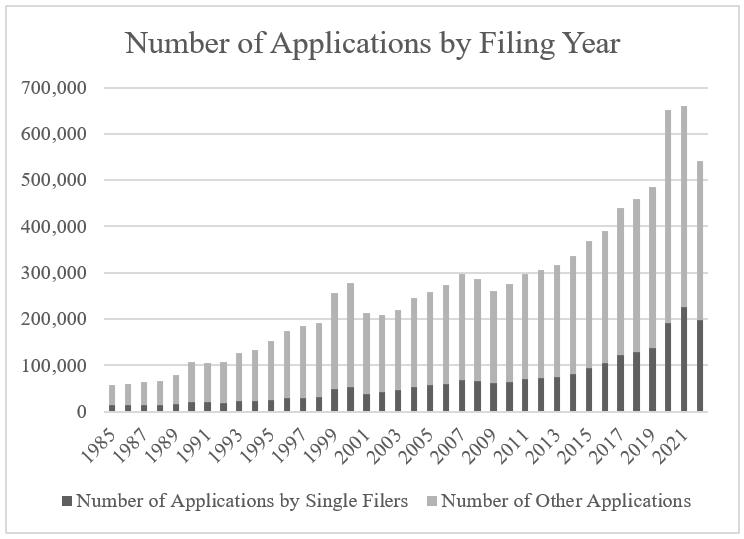

PTO data suggest that the incentives to register are growing.[192] Specifically, as shown in Figure 5, the proportion of new applications filed by single filers (entities that have not previously filed other trademark applications) has risen substantially since about 2015, from approximately 30 percent to 40 percent annually. This rate increased most sharply after 2019.[193] By comparison, as the figure shows, the proportion of new applications filed by businesses that have applied to register ten or more marks (likely bigger companies) has correspondingly declined during this time. These data are supported by Figure 6, which shows that the gross number of applications by single filers has increased slowly from the 1980s through the early 2010s. The number has doubled since 2015, from about one hundred thousand to two hundred thousand.

Figure 5. Proportion of Applications by Single and Ten+ Filers, by Filing Year

Figure 6. Number of Applications by Single Filers, by Filing Year

Figure 7. Number of Applications by Filing Year

As Figure 7 indicates, the total number of applications has risen dramatically, to more than six hundred thousand per year in two of the last three years. While there may have been other factors that contributed to this increase, it is hard to imagine that Amazon’s policies were not substantial drivers.[194] There are now just under ten million third-party businesses selling on Amazon,[195] while there were over seven hundred thousand brands in the Brand Registry just in 2021.[196] In other words, at least 7 percent of third-party businesses selling on Amazon either have PTO trademark registrations or have pending trademark applications. Many of these trademarks probably were not registered in the PTO before their entry into the Brand Registry, either because the brands were new or because the businesses using them had made the rational, pre-Amazon Brand Registry choice not to register.[197] Approximately sixteen thousand new brands enrolled in Amazon’s accelerator program in 2022—the trademark applications filed by those brands represent the ones least likely to have been filed but for the desire to be part of Amazon’s Brand Registry.[198]

It is true, of course, that Amazon has enabled many more small and medium-sized businesses to engage in interstate commerce, and that alone might explain some increase in applications to register.[199] But it seems clear that Amazon’s Brand Registry is an extra push toward registration. In Figures 5–7, we can see a small increase in trademark registrations after Amazon enabled third-party selling on its platform in 1999. However, that increase pales in comparison to the jump in small-business trademark applications after the launch of Amazon’s second version of the Brand Registry in 2017.

The increase in applications in the PTO has significantly increased examiner workload and lengthened the pendency of applications. The PTO now reports an average total application pendency of 14.4 months, compared to 9.6 months in the first quarter of 2021 (which was similar to prior years).[200] The average time to receive a first office action is 8.5 months, up from less than 5 months in the first quarter of 2021 (also similar to prior years).[201] As one expert recently said about the costs of the PTO’s delays:

Until recently, the average time until a first office action . . . allowed business owners to file trademark applications for new products or ventures, and to obtain feedback and a ‘read’ on the position of the []PTO before the trademark was placed in commercial use. Now, the longer wait time before examination has been ‘too long to wait’, [sic] and has forced many businesses to move forward with commercial introductions without this initial feedback, and with more uncertainty about their trademark rights.[202]

Likely as a response to the PTO delays and business complaints, Amazon has now made the Brand Registry available to its sellers based only on an application to register, a move that will presumably further increase the number of applications and delay registration even more.[203]

B. Trademark Extortion and Fraudulent Filings

Not only has Amazon’s Brand Registry created incentives for legitimate small businesses to register marks they might not have felt the need to register in the past, but it has also created incentives for other parties to seek registration of unregistered trademarks that are used by others on Amazon. Why? Because if that registration is successful (and now perhaps as long as the application is pending), the registrant can threaten to invoke the Brand Registry against the prior user, the legitimate owner of the mark. This situation could lead to trademark extortion, with fraudulent registrants extracting payments from legitimate businesses that are trying to avoid having their businesses taken down by Amazon.

A trademark extortion scheme of this nature was recently at issue in a case in the Eastern District of New York. In that case, the district court granted a preliminary injunction, ruling that a New York-based plaintiff was likely to succeed in its claim seeking the cancellation of the China-based defendant’s U.S. trademark registration because the defendant fraudulently used a photograph of the plaintiff’s product as its specimen of use.[204] The plaintiff had been selling home furniture and organizers on Amazon for many years using the mark SAGANIZER, but it had never attempted to register that mark.[205] The defendant seized the opportunity, filing an application to register SAGANIZER and submitting a photo of one of the plaintiff’s products as its specimen of use.[206] The PTO registered the mark in the name of the defendant on this basis.[207] The defendant then relied on its registration to complain to Amazon about the plaintiff’s use of the SAGANIZER mark, and Amazon delisted some of the plaintiff’s products.[208] Given the number of complaints by the defendant against the plaintiff’s products on Amazon, the plaintiff was at imminent risk of being suspended on Amazon altogether.[209] The plaintiff alleged that this would destroy its business, given how focused its model was on Amazon sales,[210] as many small businesses are.

This is not an isolated example of this form of trademark extortion. Presumably with the goal of maintaining the legitimacy of its Brand Registry, Amazon has recently filed multiple lawsuits, including some seeking cancellations of PTO registrations, against entities operating under the same fraudulent model as the SAGANIZER registrant.[211] According to Amazon, these entities fraudulently obtained PTO registrations of marks owned and used by businesses operating on Amazon and then used those registrations to join the Brand Registry.[212] The fraudulent registrants “then created fake, disposable websites, with product images scraped from the Amazon store, to use as false evidence when making thousands of claims that selling partners were violating their [intellectual property].”[213] Amazon alleged that one of the three entities filed almost four thousand takedown requests over a few months.[214] Amazon ultimately detected these entities’ behavior, shut down their accounts, and sued them.[215]

In response to incidents like these, Amazon has announced it is working with the PTO to prevent trademark fraud.[216] It claims to “directly receive[] and act[] upon information from the []PTO regarding registration status and parties that have been subject to []PTO sanctions” for fraudulent filings, which it uses to remove the fraudulent registrants from its Brand Registry.[217] Amazon claims to have removed five thousand false brands from its platform in this way.[218]

In recent years, as Barton Beebe and one of us have demonstrated empirically, fraudulent trademark filings using fake specimens of use have become a significant problem at the PTO, even outside of the Amazon context.[219] This work estimates that “with respect to use-based applications originating in China that were filed at the . . . PTO[] in 2017 solely in Class 25 (apparel goods), . . . 66.9% of such applications included fraudulent specimens. Yet 59.8% of these fraudulent applications proceeded to publication, and 38.9% then proceeded to registration.”[220] The extent of this fraud led Congress to pass the Trademark Modernization Act in 2020, which provided for new reexamination and expungement procedures to remove fraudulent marks from the trademark register.[221]

There are many reasons for the substantial and increasing number of fraudulent trademark filings. Until now, those investigating the issue have suspected that a major reason for this fraud—often coming from applications originating in China—is that some regional Chinese governments have been offering their citizens a financial subsidy for each U.S. trademark registration secured.[222] This subsidy encourages Chinese citizens to file fraudulent PTO trademark applications, while avoiding the costs of operating an actual business.[223]

But Amazon’s business model and Brand Registry also have contributed to the rise in fraudulent PTO trademark applications. Shrewd operators can and have extorted legitimate businesses operating on Amazon by fraudulently registering their unregistered marks, sometimes even using these businesses’ real specimens of use.

C. Descriptive and Generic Terms

For the reasons described in Part III.A, Amazon’s Brand Registry increases businesses’ incentives to seek PTO registration. It also affects the types of marks for which parties seek registration, significantly increasing business incentives to register generic and descriptive terms. Recall that trademark law categorically refuses to protect or register generic terms like “apple” for a company selling apples; it does so to prevent businesses from monopolizing those terms to the detriment of competition.[224] And descriptive terms like AMERICAN AIRLINES for an American airline are protectable only if they have developed secondary meaning.[225]

As discussed by one of us in prior work, businesses have long had an incentive to choose a descriptive or generic term as a mark when they think that “consumers will rely on [the term] to seek out their products even though consumers do not associate that term with them as a source.”[226] For example, once upon a time, a business might have chosen a generic term in the hope that a telephone operator would direct business to them when a consumer requested a particular category of goods or services.[227] But the value of that strategy has likely increased sharply in the search engine era. Now, businesses can capitalize on consumers using generic or descriptive terms as search terms, even when those consumers are not looking for any particular provider of goods or services.[228] Indeed, courts have sometimes recognized the competitive advantage that highly descriptive marks have in these search listings—marks like 24 HOUR FITNESS for a gym that is always open,[229] 1-800 CONTACTS for contact lenses,[230] HOME-MARKET.COM for homeowner referral services,[231] and BOOKING.COM for travel booking services.[232]

But there have also been historical disadvantages to choosing a generic or descriptive term to identify the source of particular goods or services.[233] Businesses that do so understand that they cannot obtain exclusive rights in a generic term, so they cannot prevent other businesses from using that term in the course of competition.[234] Likewise, businesses have incentives not to choose descriptive terms as their marks because they have to deal with the cost and uncertainty of developing secondary meaning; they also cannot use their exclusive rights to prevent competitors from using the term in its descriptive sense.[235]

Amazon’s business model, combined with its Brand Registry, disrupts this traditional calculus by increasing the benefits of using and even seeking to register descriptive or generic terms. A business might reasonably conclude that it wants to use a descriptive or generic term as a mark for its Amazon-sold goods to improve the odds of prominent placement in search results. Companies have already been adopting names like “Thai Food Near Me” or “Plumber Near Me” to promote themselves in Google search results for those exact terms.[236] The incentive to use generic or descriptive terms is likely even greater for goods sold on Amazon because Amazon’s search results put consumers directly into a position to buy the listed goods they see, regardless of brand. As one recent academic analysis of Amazon puts it, “Although in theory Amazon’s digital shelf space is limitless, in practice the first few results—especially those on the first page of the smartphone screen—are tremendously important. According to industry research, more than two-thirds of product clicks happen on the first page of Amazon’s search results, with half of those focused on the first two rows of products that appear.”[237]

Importantly, the search-related benefits are amplified for any mark in the Brand Registry because of the search result preference entailed in that program.[238] That means there is extra incentive not just to use those marks, but to try to register them. The PTO might erroneously register the mark, and even if it does not, the applicant can now get the benefits of the Brand Registry for at least the time during which the application is pending. While pending applications have always had a notice function, specifically by making a party’s claim of ownership visible,[239] applications have never before had this kind of enforceable “legal” significance.[240]

Additionally, participation in the Brand Registry makes it more likely that the business can prevent others from selling competing goods with the same generic or descriptive term.[241] For example, one Amazon seller that has filed a PTO application to register “tactical hanger” as a trademark has purportedly gotten Amazon to deactivate another seller’s listings, even though the reported seller claims to be using the term descriptively.[242] While descriptive marks risk invalidation when enforced in court, the owners of those marks enjoy significant competitive advantages with relatively little risk when they enforce their rights primarily within Amazon’s system.

Of course, none of those benefits would be available if trademark law effectively disincentivized registration of generic or descriptive terms. Amazon relies on the PTO’s trademark registry, after all. And, of course, there are rules that attempt to do just that. As we noted, generic marks are not at all protectable or registrable, and descriptive marks are not protectable or registrable without secondary meaning.[243]

But as both of us have separately argued, those rules are not sufficient. Businesses have often found loopholes that allow them to claim and even register with the PTO seemingly generic or descriptive terms, thus gaining access to the Brand Registry. For one thing, the threshold for establishing secondary meaning is regarded by many (including us) as often being too low, so a business might be able to easily clear that bar to obtain a registration.[244] For another thing, a business can often get a registration for marks that contain generic or descriptive words as long as it disclaims its rights to the unprotectable word components.[245] According to the Lanham Act, the PTO “may require the applicant to disclaim an unregistrable component of a mark otherwise registrable. An applicant may voluntarily disclaim a component of a mark sought to be registered.”[246] Indeed, 26.9 percent of applications filed from 1985 through 2016 contain disclaimed matter.[247]

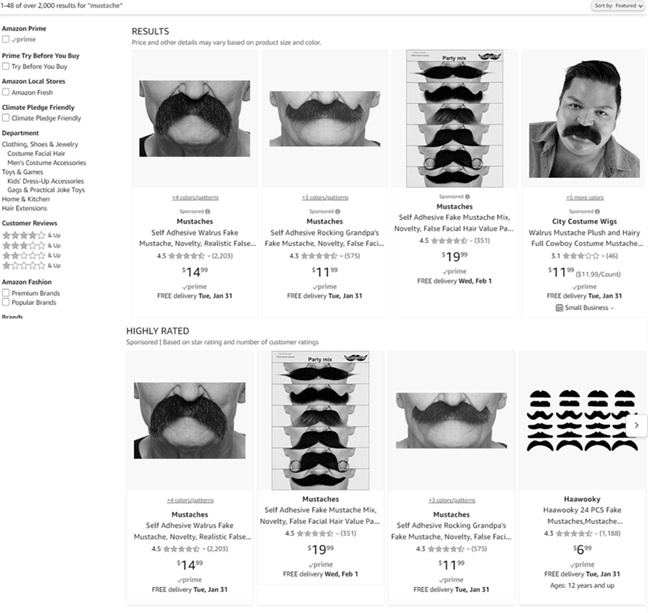

On Amazon, those disclaimers mean nothing.[248] Consider the following example, depicted in Figure 8. In 2017, a business applied to register a mark that contained a single word, MUSTACHES, for fake mustaches.[249] As is self-evident, this term is generic for mustaches. Yet the business was able to obtain a registration for this mark because the word was part of an image, and the applicant disclaimed “the exclusive right to use [‘mustaches’] apart from the mark as shown.”[250]

Figure 8. Trademark registration for MUSTACHES

Armed with this registration and despite having disclaimed rights to the word MUSTACHES for mustaches, the business can now take part in Amazon’s Brand Registry claiming, as per Amazon’s rules, the exact wording in its trademark registration: MUSTACHES.[251] The business is now prioritized in search results—depicted in Figure 9—and can call upon Amazon to prevent other fake-mustache sellers from using the term MUSTACHES. This trademark registrant has effectively bootstrapped its trademark registration, which disclaims protection for a generic term, into protection—at least on Amazon—of exactly that generic term. And although Amazon claims to consider descriptive fair use when considering infringement, there is no available public information about how it does that,[252] and at least some sellers have alleged that Amazon does not, in fact, insulate those uses.[253]

Figure 9. Amazon search results for “mustache”

As another more technologically-focused example, consider German business MXP Prime (operating as SellerX), which buys up small Amazon businesses and has received the rare unicorn valuation.[254] It recently sought to register over thirty marks for different electronics parts using the parts’ generic identifiers, such as IRF520, ATMEGA328, and DHT11 (the letters represent their maker and the number identifies the part).[255] The PTO trademark examiner, likely wondering if these identifiers are generic, and therefore unprotectable, responded with office actions asking SellerX to explain the significance of the symbols in the industry.[256] While SellerX subsequently abandoned these applications in the face of the office actions, it could have used the MUSTACHE trick and resubmitted an application to register the same alphanumeric combinations but with a drawing of anything—a sun, a clown, a hat—accompanying the word while disclaiming the alphanumeric combinations themselves. This would have allowed SellerX to register trademarks with generic text that would then hold muster in the Amazon Brand Registry.

In all, Amazon’s business policies have bulked up the incentive for businesses to seek registration of generic and descriptive terms, often using loopholes to get the benefits of both trademark registration with the PTO and admission to the Amazon Brand Registry.

D. Nonsense Marks

Another way Amazon’s policies have influenced the marks parties seek to register is reflected in the new phenomenon of nonsense marks. These are marks that are comprised of random strings of letters or numbers that are not comprehensible as words or as symbols with any meaning.[257] As Grace McLaughlin has noted, these marks pose serious conceptual problems for trademark law. Most obviously, they confound distinctiveness determinations because the marks seem to be fanciful (and therefore inherently distinctive). Nonsense marks do not provide any information about the goods or services and do not have any other ordinary meaning.[258] But fanciful terms are generally considered especially strong trademarks because they are assumed to be understandable only as trademarks.[259] Nonsense marks flout that assumption because they are not comprehensible as trademarks or, for that matter, as anything at all.

It is also extremely difficult to determine whether these marks are being used as trademarks.[260] As discussed above, the PTO refuses to register claimed marks that do not function as marks because those features do not indicate the source of the goods or services with which they are used.[261] Those refusals for what the PTO calls “failure to function” are typically based on contextual determinations: They focus on whether a particular sign functions as a mark as it is shown in a particular specimen of use.[262] That is why the failure-to-function doctrine has primarily focused on the location of a claimed mark and not its intrinsic nature. Consumers often recognize that a sign is a trademark when it is located in a prototypical “trademark space,” even if they have not previously encountered that mark, but signs used in other places may not be understood by consumers as trademarks at all.[263] Nonsense marks likely do not function as marks, but the reason is their intrinsic nature, not that they do not indicate source when used in a particular manner. They are not vehicles for any meaning, let alone trademark meaning.[264]

Even likelihood of confusion, the standard used to assess trademark infringement, is complicated in the context of nonsense marks. Trademark law does not have a good way of assessing similarity when one of the things being compared is not comprehensible as a word or understandable as a symbol. Similarity is usually assessed in terms of sight, sound, and meaning, and only sight is even possibly relevant for nonsense marks.[265] Is NXLYP confusingly similar to NYLPX, or for that matter to PTXWA? On the one hand, these marks might not be confusing because confusion depends on the ability to attach external meaning to the terms—in that sense, because people do not attach any meaning to nonsense marks, they might rarely be similar enough to cause confusion. On the other hand, it might be that all nonsense marks are potentially confused with other nonsense marks because none of them are distinct. Either way, trademark law has no good framework to evaluate such confusion.[266] Perhaps just as troubling is that a nonsense mark might be seen as confusingly similar to a more traditional mark, such as McLaughlin’s examples of MAJCF being confused with MAJI, or JANRSTIC with JANSTICK, preventing the more traditional mark applicant from being able to register their mark in the face of the already-registered nonsense mark.[267]

Precisely because nonsense marks are not comprehensible, they are extremely unlikely to be memorable as marks. For that reason, there was never previously much incentive to use nonsense marks.[268] Regardless of the availability of legal protection, a mark is first and foremost a marketing tool that is supposed to indicate the source of goods.[269] If the mark a business chooses is not memorable, it will not provide real commercial benefits because consumers are not likely to attach any meaning to it.

Amazon’s policies significantly change those incentives. The usual disincentive against a nonsense mark disappears or is greatly diminished for a third-party business selling on Amazon. For one thing, participating in Amazon’s Brand Registry does not just help a business enforce its mark, a benefit that probably does not matter much to a nonsense mark user, but it gives the participating business valuable preference in Amazon’s search algorithm.[270] Moreover, Amazon’s business model diminishes the incentive to choose memorable marks in the traditional sense because businesses can rely on consumers being attracted to the AMAZON mark and the Amazon platform. Many consumers also focus more heavily on consumer reviews and search results listing products based on searches for the type of good rather than for the branded good than they would in other shopping contexts.[271] When searching and purchasing are not necessarily done by people who are looking for particular brand names, businesses just need something to make the algorithm prefer them.[272]

Indeed, the forgettability of nonsense marks might be precisely their point. Owners of nonsense marks can collect product reviews on their listings. If they are positive, they can rely on the search algorithm to deliver them more customers. If the reviews are negative, they can easily relaunch under another forgettable nonsense mark and avoid the reputational consequences of those reviews.[273] In this way, nonsense marks undermine the very function of trademarks: an easy way for consumers to attach reputation to the right party.[274]

Despite their conceptual difficulty, the current substantive requirements for PTO registration make nonsense marks attractive to businesses selling on Amazon that simply want a registration to participate in the Brand Registry. Nonsense marks are likely to be treated as fanciful and therefore inherently distinctive, they are likely to be seen as functioning as marks despite being gibberish, and they are unlikely to be confusingly similar to other marks given their composition. For these reasons, nonsense marks are relatively easy to register and to bootstrap into the benefits of the Amazon Brand Registry.

The PTO data bear this out in our analysis. To approximate the rate of nonsense marks in trademark applications and publications,[275] we counted the number of applications and publications with a word mark of more than four characters, comprising only one word, that was not of the one hundred thousand most frequently used words in American English,[276] and that contained either four consonants in a row or three vowels in a row.[277] This approach properly counts ELXXROONM, SUJIOWJNP, XUFFBV, and LXCJZY as nonsense marks. But the approach is both somewhat overinclusive and underinclusive. It counts OLDSMOBILE and SHIRTCRAFT as nonsense marks when it should not, but it does not include EARKOHA as a nonsense mark when it likely should. Even with these mistakes, we think counting marks using a metric like this one can reveal trends in nonsense marks over time, especially when there is no reason to think it undercounts or overcounts marks at different rates out of proportion to true nonsense marks over time.

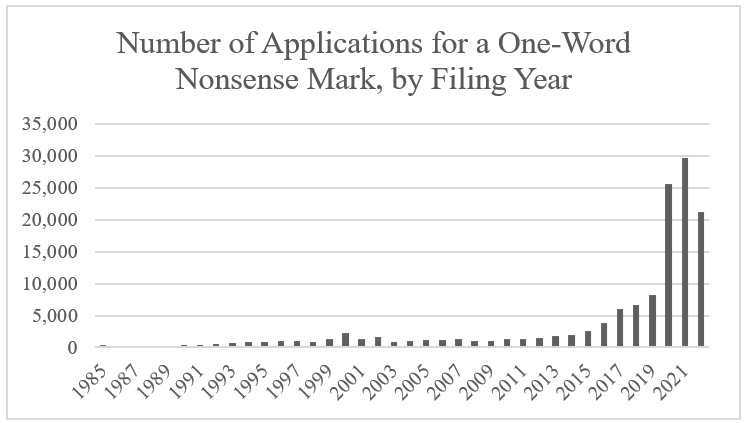

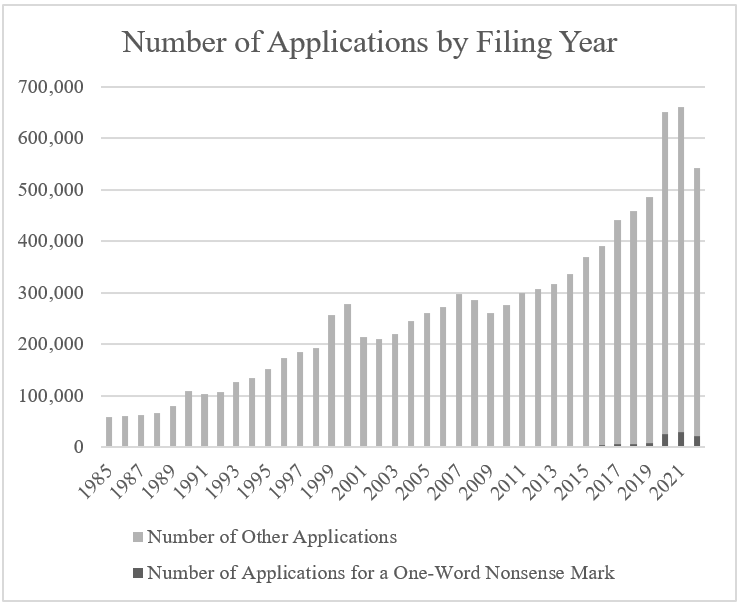

We find that the number of applications to register nonsense marks has increased markedly in recent years. As Figure 10 shows, the proportion of applications with one-word nonsense marks has risen sharply in just the past few years. For decades, applications for nonsense marks accounted for only about 0.5 percent of applications. That proportion is now approximately 4.5 percent. As the number of applications has risen steadily over time, we also find, as depicted in Figures 11 and 12, that the absolute number of applications comprised of a nonsense mark has risen from almost none for decades, to over twenty thousand annually in the past few years.

Figure 10. Proportion of Applications with a One-Word Nonsense Mark

Figure 11. Number of Applications for a One-Word Nonsense Mark, by Filing Year

Figure 12. Number of Applications by Filing Year

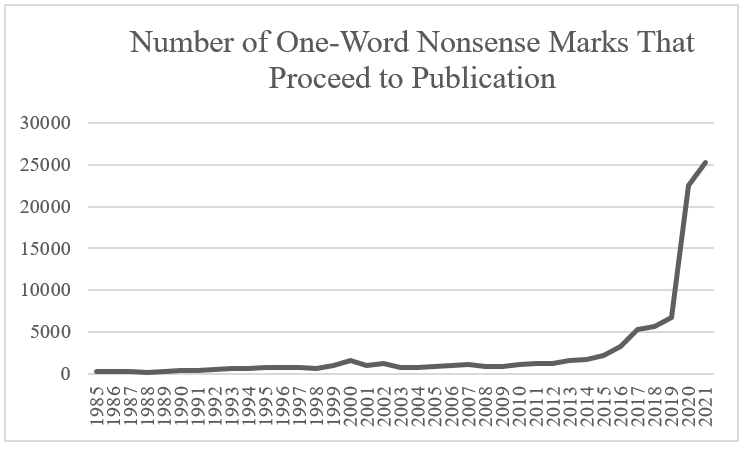

Corresponding to the increase in applications, more nonsense marks have been published for opposition by the PTO. As Figure 13 demonstrates, nonsense marks are published at roughly the same rate as all other non-nonsense marks. Thus, the rising number of nonsense mark applications proceeding to publication in recent years reflects the substantial increase in the number of newly filed nonsense mark applications, not any increased propensity of the PTO to publish nonsense mark applications. As Figure 14 shows, over twenty-five thousand nonsense marks proceeded to publication in 2021, the most recent year for which we are likely to have nearly complete rates of publication, as compared to nearly zero such marks annually going back decades, except in recent years.

Figure 13. Rates of Publication for Nonsense Marks and All Marks

Figure 14. Number of One-Word Nonsense Marks That Proceed to Publication

E. Amazon’s House Brands

A final important way that Amazon’s business model and Brand Registry have shifted the trademark system, and competition more broadly, is Amazon’s focus on first-party sales, rather than the third-party sales explored thus far. Recall that when Amazon launched, it engaged exclusively in first-party sales.[278] While its business model has shifted toward substantial numbers of third-party sales, Amazon still engages heavily in first-party sales, and those sales generate the largest share of its revenue.[279]