Originality’s Other Path

Although the U.S. Supreme Court has famously spoken of a “historic kinship” between patent and copyright doctrine, the family resemblance is sometimes hard to see. One of the biggest differences between them today is how much ingenuity they require for earning protection. Obtaining a patent requires an invention so innovative that it would not have been obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the art. Copyright, by contrast, makes no such demand on authors. It requires an original work of only minimal creativity.

Except sometimes it doesn’t. Puzzlingly, in some copyright cases dealing with musical arrangements, courts have demanded a patent-like level of creativity from putative authors. While these cases might seem like outliers, they have a pedigree that is both lengthy and largely unrecognized. The proposition that copyright originality should require patent-style inventiveness beyond artisans’ everyday creations dates back to an 1850 music-infringement decision by Justice Samuel Nelson. In fact, only four months later, Nelson himself would author the Supreme Court patent opinion that is now credited as the touchstone for patent law’s own nonobviousness doctrine. His corresponding vision for copyright, though, came first.

Drawing on original archival research, this Article challenges the standard account of what originality doctrine is and what courts can do with it. It identifies Nelson’s forgotten copyright legacy: a still-growing line of cases that treats music differently, sometimes even more analogously to patentable inventions than to other authorial works. These decisions seem to function as a hidden enclave within originality’s larger domain, playing by rules that others couldn’t get away with. They form originality’s other path, much less trod than the familiar one but with a doctrinal story of its own to tell. Originality and nonobviousness’s parallel beginnings reveal a period of leaky boundaries between copyright and patent, when many of the Justices considered a rule for one to be just as good for the other. Their recurring intersections, meanwhile, muddy today’s conventional narrative about copyright’s historic commitment to protecting even the most modestly creative works.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

[A]n opera is more like a patented invention than like a common book . . . .

–Thomas v. Lennon, 1883[2]

The Supreme Court has famously spoken of a “historic kinship” between copyright and patent law, which both seek to encourage their own form of creative production by granting exclusive rights.[3] Sometimes, though, the family resemblance is hard to see. One of the biggest differences between the two regimes is how much ingenuity they require for earning legal protection. Under copyright’s originality standard, a work of authorship need only “possess[] at least some minimal degree of creativity,” a bar that the Supreme Court has emphasized is “extremely low; even a slight amount will suffice.”[4] Earning a patent, by contrast, requires far more. An invention must not “have been obvious . . . to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.”[5] As the Court has stressed in its most recent interpretation of this nonobviousness standard, the bar is meant to be high enough to exclude “the results of ordinary innovation.”[6]

Most intellectual property (IP) commentators today think that this difference in legal protection is sensible, and there’s a large literature devoted to justifying it.[7] One argument is that the two fields are simply trying to maximize different things, with patents trying to funnel activity into a problem’s most efficient solution and copyright trying to generate the widest abundance of information possible.[8] Another is that users of technological goods tend to welcome a high degree of newness, while audiences for expressive works tend to devalue works that they deem too new.[9] Still another is that, even if copyright had a good reason to encourage works of greater creativity, it lacks the sort of objective criterion for assessing value that patent law can deploy for scientific inventions.[10] While these theories differ, they all end up in the same place: a patent should require the demonstration of above-average ingenuity, and a copyright should not. And that’s exactly what the two bodies of law give us.

Except when they don’t. Puzzlingly, in some copyright cases involving music, courts have demanded a patent-like level of creativity from putative authors.[11] Take, for example, the district court decision that held that a musical arrangement of an earlier, sparsely notated lead sheet lacked sufficient originality because “there must be present more than mere cocktail pianist variations of the piece that are standard fare in the music trade by any competent musician.”[12] The notion that protection should depend on outperforming merely “competent” peers in the field sounds much like patent’s nonobviousness test but nothing like the usual copyright standard.[13] Still, on appeal the Second Circuit blessed that formulation.[14] Another judge subsequently employed it as the governing rule in the recent, high-profile litigation over the copyright status of the song We Shall Overcome.[15]

One could understandably brand these examples outliers. And certainly, many commentators do.[16] Yet these high-originality cases have a pedigree that is both lengthy and largely unrecognized. The proposition that copyright originality should require patent-style inventiveness beyond the everyday creations of artisans in the field dates back to Justice Samuel Nelson’s opinion in one of the first reported music infringement cases in the United States, 1850’s Jollie v. Jaques.[17] In fact, only four months later, Nelson himself would author the Supreme Court patent case that is now credited as the touchstone for patent law’s own nonobviousness doctrine, Hotchkiss v. Greenwood.[18] His parallel vision for copyright, though, came first.

If Nelson had had his way, both patent and copyright doctrine alike would have denied protection to everyday craftsmen—“mechanic[s],” as he put it in the era’s typical parlance—and reserved it only for “genius[es]” who made a large enough leap beyond the rest of the field.[19] As extraordinary as that proposition should sound when measured against copyright’s traditional originality standard, Nelson’s opinion in Jollie initiated a small but significant line of cases seemingly defying that standard up through the present day.

These cases have something curious in common: they’re all about musical arrangements. Explicitly or implicitly, each treats music differently than literary works, sometimes even declaring that music is more analogous to patentable inventions than to other copyrightable subject matter. Justice Nelson’s copyright legacy thus hasn’t been the baseline protectability threshold that he originally articulated. Instead, it’s been a mechanism through which later courts could selectively raise that threshold when they encountered musical subject matter.

Drawing on original archival research, this Article identifies that forgotten legacy. Jollie’s heightened threshold is originality’s other path, much less trod than the familiar one but with a doctrinal story of its own to tell. I trace that path from its start in 1850 to its most recent section in 2017.

After a nutshell summary of each regime’s early history in Part I below, I turn in Part II to a detailed study of the disputes that culminated in the Jollie decision on the one hand and the Hotchkiss decision on the other. Part III describes the trajectory that each body of law has taken since, focusing particularly on the several music cases that have tried to apply Jollie’s heightened creativity threshold, even as the rest of copyright law had seemingly left it behind. Many of these cases might have ended up quite differently without supporting roles played by individuals with idiosyncratic backgrounds, from a music publisher-turned-inventor to a composer-turned-lawyer to a judge-turned-composer.

Beyond the personalities involved, though, I argue in Part IV that this history offers three important lessons for contemporary copyright theory. First, it provides an unlikely but powerful example in support of the Supreme Court’s proposition that copyright and patent doctrine have indeed cross-pollinated. After all, the nonobviousness element that is today called “the heart of patent law”[20] and “the final gatekeeper of the patent system”[21] was, at its start, seen as a viable addition to both copyright and patent law alike.

Second, this history suggests some proof of concept for how judges can tailor seemingly monolithic copyright standards to particular subject matter’s idiosyncratic needs. IP commentators have frequently noted that a single set of uniform rights is ill-suited to govern a world in which the affected industries and creative fields can vary wildly in their production costs, norms, risk tolerances, and so on.[22] Copyright’s dalliance with a nonobviousness-type originality threshold for musical derivatives shows judges’ capacity to reduce that uniformity by applying a supposedly homogeneous standard in heterogeneous ways depending on the nature of the dispute.

Finally, courts’ selective application of the higher creativity threshold for musical works demonstrates how supposedly vestigial precedents can reemerge in unpredictable and contingent ways. Even as Nelson’s vision for patents took over that entire body of law, judges spent six decades all but ignoring his simultaneous vision for copyrights. From the vantagepoint of a turn-of-the-century observer, the Jollie standard had been dead on arrival. In fact, that standard might never have appeared again but for the litigation strategy of one defendant—who happened to have both legal and musical training—in an infringement case from 1914, over half a century after Jollie was decided.[23] This episode of copyright history shows, in short, the messiness of doctrinal evolution through the common-law process.

I. Copyright And Patent Protection in the Early Nineteenth Century

Copyrights and patents are each intended to promote their own form of innovation through the grant of their own form of exclusivity.[24] Copyrights cover works of authorship like books, music, and movies, while patents cover functional inventions like pharmaceuticals, smartphone components, and manufacturing methods. The same clause in the Constitution empowers Congress to legislate in both spheres in order to “promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.”[25] Most commentators understand that power to be justified by the likelihood that informational goods, whether authorial or technological, would be undersupplied if imitators could easily swoop into the market and undercut the originator without having to bear the same fixed costs of creation.[26] A patent’s or copyright’s exclusivity thus provides an appropriability mechanism that can encourage investment in creative activity that might not otherwise take place.

But before handing out that exclusivity, each regime needs to identify what’s worth protecting. One of the main screening tools available is a creativity threshold, a bar of ingenuity over which authors or inventors must leap to obtain the legal entitlement.[27] Copyright screens through its originality requirement,[28] patent law through its nonobviousness requirement.[29]

The two doctrines are often discussed side by side, not only because they perform a similar role but also because they perform it so differently.[30] For patents, only the unconventional need apply. Even an entirely novel invention will be denied a patent if the differences between it and what came before “would have been obvious . . . to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the claimed invention pertains.”[31] In practice, according to the Court’s most recent exploration of the standard in KSR Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., “a court must ask whether the improvement is more than the predictable use of prior art elements according to their established functions.”[32] KSR further emphasized that some activity may be creative but would nevertheless fall within the statute’s “ordinary skill” zone. “A person of ordinary skill,” it said, “is also a person of ordinary creativity, not an automaton.”[33]

For copyrights, by contrast, the Court has set a bar that’s famously easy to clear. In its 1991 decision Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Services Co., the Court declared that “the requisite level of creativity is extremely low; even a slight amount will suffice.”[34] Unlike the technological inventions that patent law seeks to encourage, expressive works need not be especially surprising or clever to earn copyright protection. In fact, the Court all but excluded nonobviousness from the copyright equation when it stated that “[t]he vast majority of works make the grade quite easily, as they possess some creative spark, ‘no matter how . . . obvious’ it might be.”[35] Unlike patent law, as one court of appeals summarized the difference, copyright “does not require substantial originality” but instead “only enough originality to enable a work to be distinguished from similar works that are in the public domain.”[36] That’s generally not a tall order. In John Duffy’s colorful example, a ten-year-old who spends an hour on a homework assignment by writing a trite and mediocre story that earns a bad grade has probably still earned a copyright to go with it.[37]

Especially given contemporary copyright doctrine’s renunciation of any similar validity demands, commentators often point to nonobviousness as the feature that gives patent law its unique doctrinal identity within the IP domain.[38] It has famously been called “the heart of our patent system” and its “final gatekeeper.”[39] Among all patent validity elements, it is the only one that “fully implements the core notion of patent law that patents should be granted only for significant advances over previously known technology.”[40] One 1998 study found that, among patent validity issues, it was both the most frequently litigated and the most likely to lead to an invalidity judgment.[41]

Though Congress only codified this defining feature in 1952, the Supreme Court has traced it back a century earlier to its 1851 decision in Hotchkiss v. Greenwood.[42] In the Court’s view, the statutory nonobviousness requirement “was intended merely as a codification of judicial precedents embracing the Hotchkiss condition, with congressional directions that inquiries into the obviousness of the subject matter sought to be patented are a prerequisite to patentability.”[43] Hotchkiss, not any particular act of Congress, had first established “the condition that a patentable invention evidence more ingenuity and skill than that possessed by an ordinary mechanic acquainted with the business.”[44]

But the Court’s decision in Hotchkiss, it turns out, wasn’t the first judicial opinion to hold squarely that the availability of IP protection should depend on outshining the everyday output of one’s peers. Only a few months earlier, in the fall of 1850, there was another. Justice Samuel Nelson, the same judge who authored the Hotchkiss majority opinion, issued a trial-court decision while riding circuit that announced a remarkably similar standard, one that required creators to surpass that “which any person of ordinary skill and experience in [the field] could have made.[45] That standard, however, was not for patents. It was for copyrights.

To appreciate the significance of Nelson’s intervention, one first needs to understand that copyrights and patents were far more similar in the early nineteenth century than they are today.[46] Thanks to parallel strands of cases pioneered by Justice Joseph Story, early IP law’s most influential jurist, neither demanded any special ingenuity. The remainder of this Part briefly reviews these cases, setting the stage for Nelson’s double shakeup that follows in Part II.

A. The Origins of Copyright’s Originality Standard

When the first Congress passed the United States’ inaugural Copyright Act in 1790, originality didn’t yet exist as a limitation on copyrightability. Any text that fell into an appropriate class of subject matter—books, maps, or charts—sufficed, so long as its author was a U.S. citizen or resident. As Oren Bracha summarized the history of this period, “At its infancy American copyright law did not include a lax originality threshold. It included no doctrine or concept of this kind at all.”[47]

In two seminal cases, however, Justice Story simultaneously introduced the new requirement, while also ensuring that it wouldn’t be onerous to satisfy. First, in Gray v. Russell,[48] he rejected an infringement defense arguing that the copied work wasn’t “substantially new,” and thus simply too derivative to merit protection.[49] The work at issue was a compilation of editorial notes and revisions to a preexisting Latin textbook. To be sure, Story wrote, the putative author who brings the claim must invest some intellectual labor in the work.[50] No one could secure a copyright on that which had been copied outright from another. But whether that labor yielded something “substantially” new was irrelevant. Rather, the real question presented was whether the revisions “are to be found collected and embodied in any former single work.”[51] Because they were not, the defense failed. Story conceded that other editors might perhaps arrive at a similar result if they were to work on the problem independently. Yet the likelihood of such convergence, he held, is no bar to copyright:

There is no foundation in law for the argument, that because the same sources of information are open to all persons, and by the exercise of their own industry and talents and skill, they could, from all these sources, have produced a similar work, one party may at second hand, without any exercise of industry, talents, or skill, borrow from another all the materials, which have been accumulated and combined together by him.[52]

Six years later, a second dispute over copying a textbook gave Story an opportunity to expound further on just how minimal the originality threshold was. In Emerson v. Davies,[53] the defendant tried an argument similar to the one that had failed in Gray, that the plaintiff’s material wasn’t “new, or invented by him.”[54] Story’s reaction was, as before, so what if it wasn’t? Authors of arrangements and combinations of preexisting materials are perfectly entitled to a copyright so long as “it be new and original in its substance.”[55] In a move that reflected his already-developed jurisprudence on patentability’s similarly low bar,[56] Story reasoned that copyrights ought to demand no more of an intellectual leap than do patents.[57]

Story then waxed philosophical—and decidedly anti-romantic—on the inherently cumulative, incremental, and derivative nature of literary production: “In truth, in literature, in science and in art, there are, and can be, few, if any, things, which, in an abstract sense, are strictly new and original throughout. Every book in literature, science and art, borrows, and must necessarily borrow, and use much which was well known and used before.”[58] To demand otherwise as a condition of copyrightability would, he reasoned, be folly. Such an argument would prove far too much, leaving “no ground for any copy-right in modern times, and we should be obliged to ascend very high, even in antiquity, to find a work entitled to such eminence.”[59]

In Story’s hands, then, originality emerged as a requirement of intellectual labor, not any particular yardstick of ingenuity or artistic merit. All that was required to pass the test was producing a work by exercising one’s “own skill, judgment and labor,” and “not merely copy[ing] that of another.”[60] Shortly thereafter, George Ticknor Curtis included that standard in the section of his influential copyright treatise devoted to the issue of “the originality necessary to a valid copyright.”[61] Citing Emerson, Curtis wrote that the fledgling originality element turned only on whether the author had “actually produced anything of his own, and not whether his production [was] better or worse than the productions of others.”[62] Moreover, “[t]he law [did] not require that the subject of a book should be new.”[63] It required only that the book “contain[] any substantive product of his own labor.”[64] This version of originality, which by the mid-nineteenth century seemed to represent the legal mainstream, was deliberately modest. It was essentially a no-copying regime, eschewing any interest in the author’s talents or competence on display. In that sense, Story’s originality doctrine began as a way to preempt any notion that copyright law might care where an author’s work stood in relation to that of their peers.[65]

B. The Invention of Patent’s Invention Standard

Early American patent statutes didn’t expressly indicate that a novel invention should be denied a patent for want of inventiveness. The first Patent Act, passed in 1790, at least required patentable inventions to be “sufficiently . . . important,”[66] but that language lasted only three years before Congress overhauled the entire statute.[67] No court ever considered what the requirement meant for patentability.[68] Thomas Jefferson, who as Secretary of State voted on patent applications under that short-lived act, drafted a bill in 1791 that parenthetically noted a defendant should be permitted to show that the invention-in-suit was “so unimportant and obvious that it ought not to be the subject of an exclusive right.”[69] Given his choice of words, some modern commentators credit Jefferson as an early proponent of raising patent law’s ingenuity threshold.[70] That bill, however, never passed and, though the record is murky, might never have been introduced in Congress at all.[71] His draft doesn’t appear to have had much of an effect on his contemporaries.[72] Perhaps Jefferson was ahead of his time. It would take several decades before courts would begin warming to such a restriction on patentability.

Indeed, the first patent case to address what we’d today call a nonobviousness requirement was a vehement rejection of the proposition that any such requirement exists.[73] As in copyright, Justice Story led the way. The 1825 case of Earle v. Sawyer presented the question of whether one could patent an improvement to a shingle mill by substituting a circular saw for the reciprocating saw that such machines had historically featured.[74] The patentee, who also happened to be the inventor of the previous-generation shingle mill, accused the defendant of infringing the updated version. At trial, the defendant put on testimony showing that the substitution of one saw for another “was so obvious to mechanics, that one of ordinary skill, upon the suggestion being made to him, could scarcely fail to apply it in the mode which the plaintiff had applied his.”[75] The jury nevertheless returned a verdict of infringement.[76]

In seeking a new trial, the defendant argued that the patentee’s addition of a circular saw to the existing shingle-mill apparatus was “so simple, that, though new, it deserves not the name of an invention.”[77] Obtaining a patent, he contended, required not just a new and useful thing but also “mental labor and intellectual creation.”[78] A true invention ought to be something that “would not occur to all persons skilled in the art, who wished to produce the same result.”[79]

Story disagreed. Patent law, he wrote, didn’t care whether a new and useful invention would have been obvious to mechanics or only to certifiable geniuses—it would still be an invention either way:

It is of no consequence, whether the thing be simple or complicated; whether it be by accident, or by long, laborious thought, or by an instantaneous flash of mind, that it is first done. The law looks to the fact, and not to the process by which it is accomplished. It gives the first inventor, or discoverer of the thing, the exclusive right, and asks nothing as to the mode or extent of the application of his genius to conceive or execute it.[80]

Because Story considered patent doctrine indifferent to a particular invention’s level of ingenuity, he sustained the infringement verdict. Earle was thus an emphatic disavowal of precisely the same sort of ordinary-skill filter that’s now familiar to modern patent practitioners.

That low threshold, like the analogous one that Story would erect for copyright cases, “dominated the first half of the century,” essentially defining the early law of patentability.[81] Refusing to discriminate between high- and low-ingenuity inventions, as Story had instructed, made some sense when everyday laborers without any specialized, technical training were regularly developing industrial innovations.[82] On top of that, there may have been less social need for a rigorous screening process so long as the pace of technological change remained slow enough.[83]

Justice Levi Woodbury, who in 1845 was appointed to fill Story’s seat on the Court as Circuit Justice, repeatedly instructed juries that patents required no heightened inventiveness. In Adams v. Edwards, for example, he stated that a new and useful combination of old elements was patentable “no matter how slight is the change.”[84] Similarly, in Woodworth v. Edwards, he denied the defense’s request to instruct the jury that “if the mere changing [of the prior art] were only such an alteration or addition as any mechanic of ordinary skill would naturally make, then the mere change . . . was not the subject of a patent.”[85] Consistent with this approach, Woodbury would later dissent stridently in the Hotchkiss decision that started the erosion of Story’s regime.[86]

There were, to be sure, some initial cracks in Earle’s edifice as the century neared its halfway point. At least two cases in the 1840s were receptive to considering ordinary mechanical skill when assessing an invention’s novelty.[87] Confusingly, one of these decisions belonged to the otherwise Earle-compliant Woodbury.[88] Even more insistent was Willard Phillips’s 1837 patent treatise, which posited a “general rule . . . that any change or modification of a machine or other patentable subject, which would be obvious to every person acquainted with the use of it, and which makes no material alteration in the mode and principles of its operation, and by which no material addition is made, is not a ground for claiming a patent.”[89] That proposition, of course, sounds a lot like the modern nonobviousness test—and a lot like the one that Story had rejected in Earle. Where Phillips found this supposedly already-established rule is unclear. Congress had passed a new Patent Act only a year earlier, and the rule was nowhere to be found within it.[90] And while judges might have had room in the normal common-law process to narrow the doctrinal concept of invention, the leading case had expressly repudiated that move. U.S. courts had not once approved of the rule that Phillips had attributed to them.[91] As a result, some contemporary commentators have accused Phillips of prescribing law under the guise of describing it.[92]

In any event, notwithstanding Phillips’s treatise, the factual issue of whether particular inventions would have been obvious to ordinary mechanics was not typically litigated in the decades following Earle.[93] By the century’s midpoint, the notion that patent law imposed a separate ingenuity limitation on top of the baseline novelty requirement was still largely out of bounds.

Justice Nelson’s majority opinion in Hotchkiss would plant the seed that would eventually create that limitation. First, though, he would try to do the same thing for copyright law.

II. Justice Nelson’s Heightened Thresholds

It’s not surprising that early nineteenth-century defendants had tried, even if unsuccessfully, to convince courts to distinguish between ostensibly genuine creators on the one hand and ordinary mechanics on the other. Outside the courtroom, whether in technological or literary innovation, many others were doing the same thing.

Most technologists during this period were mechanics in a literal sense. Their field of practice involved working with machines.[94] Branding someone a “mechanic” was thus not so much descriptive as it was rhetorical, meant to designate the purported inventor’s labors as intellectually inferior.[95] It was, in historian Alfred Young’s characterization, a colonial-era “term of derision” used against tradesmen “by those above them.”[96] In 1807, a pro-patent association known as the New England Association of Inventors and Patrons of Useful Arts published a pamphlet proclaiming that the inventor is “highest in the scale of useful beings,” with the farmer and mechanic following behind him.[97] The inventor was the one “to whom society is most indebted,” not to mention the one “from whom that same society wrest[s] his property without his consent” when patent law fails to provide adequate protection.[98] Inventors, the creed declared, sat on a more elevated plane than the rest.

Authors and artists, for their part, had in England begun to receive a similar conceptual isolation from mechanics. Up through the first half of the eighteenth century, authors had been considered their own form of craftsmen, skilled operators of rhetorical and prosodic rules.[99] When their work surpassed that expectation, audiences assumed that some external force—a divine muse, perhaps—must have been responsible.[100] Later in that century, however, that once-divine inspiration was reconceived as the Romantic author’s internal voice, a voice possessed only by true geniuses.[101] At the same time, English authors were growing concerned about the lower barriers to entry afforded by writing’s increasing commodification.[102] In response, they began constructing themselves as a professional literary class that stood apart from “mere [m]echanics” who sought to emulate them.[103] Thus, for example, the poet Edward Young contrasted the organic lifeform of original authorship with second-comers’ machine-like imitations: “An Original may be said to be of a vegetable nature; it rises spontaneously from the vital root of Genius; it grows, it is not made: Imitations are often a sort of Manufacture wrought up by those Mechanics, Art, and Labour, out of pre-existent materials not their own.”[104] Similarly, the playwright Henry Fielding accused derivative writers of being “mere Mechanics, to be envious and jealous of a Rival in their trade.”[105] Sir Joshua Reynolds told the students of the Royal Academy of Art in 1770 that “intellectual dignity . . . enobles the Painter’s art, that lays the line between him and the mere mechanic.”[106] And according to an 1837 account, an unnamed author who wanted to disparage the work of Alexander Pope called him “no poet, but a mere mechanic, who gleaned thoughts from others.”[107]

Against that cultural backdrop, one could understand how defense attorneys might plausibly challenge works or inventions that seemed insufficiently pathbreaking to merit the law’s protection. With Justice Story on the bench, that strategy had failed. But Story died in 1845. Nelson, who had joined the Court the same year,[108] turned out to be far more receptive.

In the following two sections, I examine Jollie v. Jaques,[109] in which Nelson announced that copyright should indeed screen out the work of mere mechanics, and then his more famous effort four months later in Hotchkiss v. Greenwood[110] that did the same for patents. Although the basics of their reported decisions have long been known, many of the litigation details that I describe here have not. They reveal a moment in jurisprudential time at the century’s midpoint when a heightened creativity threshold looked just as likely for copyright law as it did for patent.

A. Copyright: Mechanics Versus Authors

Nelson’s 1850 circuit court opinion in Jollie is the case that best stands for a stronger creativity threshold in U.S. copyright law. It was also the first significant break from Story’s prevailing low-originality standard. Curiously, though, Story’s decisions in Emerson and Gray seem never to have been mentioned over the course of the litigation.

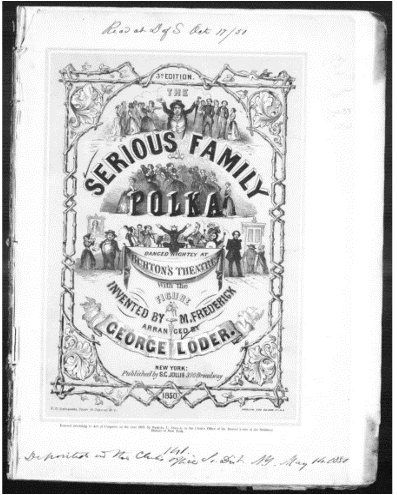

The case involved the work of composer George Loder. Loder had arranged the incidental music for the dramatic comedy The Serious Family that was then playing at a New York theater where he also served as music director. One of the selections from that music was a polka number that came to be called eponymously The Serious Family Polka. On February 15, 1850, Loder arranged his theater version of the piece for piano. Three days later he then assigned his interest in that arrangement to the music publisher Samuel C. Jollie.[111] Though Jollie’s name is now known primarily from the case caption of a copyright dispute, he was also an inventor. (In fact, a few years later he would achieve some minor fame in the annals of election transparency as the inventor of a patented ballot box whose receptacle was a glass globe, ensuring that “bystanders may see every ballot which is put in, see all the ballots that are in, and see them when taken out.”)[112]

Jollie published Loder’s piano arrangement of the polka, reproduced in Figure 1 below. Reflecting the historical meaning of the word “invention” that covered both scientific and artistic novelty, Jollie’s edition credited the choreographer with “invent[ing]” the dance figures.[113] Jollie secured copyright protection for the piece by depositing it with the district court on February 20.[114] Loder’s polka was based on an earlier German piece, The Roschen Polka.[115] According to Jollie, at least, Loder’s adaptation required much “labor, time and musical knowledge and skill.”[116]

Fig. 1: Cover page to Samuel Jollie’s sheet music for The Serious Family Polka[117]

Within days, the music publisher Jaques & Brother released a competing piano edition of the polka.[118] When Jollie got wind of it, he approached John and James Jaques, the partners who gave the publisher its name, and tried to convince them to cease.[119] They refused. While they admitted that they had been selling sheet music under the same title as Jollie, they insisted that they had purchased the rights to it from a third party and “had the music in process of publication and the title page engraved before they knew or had heard of” Loder’s version.[120]

On February 26, six days after he had secured the copyright on the piece, Jollie sued in equity to enjoin the Jaques’s continued distribution of the music.[121] The defendants argued that “the only similarity” between the two polkas lay “in the melody,” which had been “copied and taken from a composition by some German called the Röschen Polka and which ha[d] been performed by various bands in this city” before Jollie had ever published his version. Loder, they insisted, “has made no change in the melody whatever and has added no original matter to the composition.”[122] Instead, he’d merely “adapted the old melody to the Piano forte.”

In support, they used a now-familiar infringement-litigation strategy that was innovative for its day: expert witnesses.[123] First was a declaration from the composer and music instructor George H. Curtis. Curtis opined that the parties’ two polkas were “different in their arrangement,” that the defendants’ “contains several bars of matter” that the plaintiff’s version lacked, and that multiple bars between them differed in the arrangement of treble and bass notes.[124] Moreover, Curtis continued, Jollie’s polka had been “substantially copied in melody” from the underlying German polka, “the only difference being that [the German work] was arranged for the clarinet while the same [melody] appears in [Jollie’s version] arranged for the Pianoforte.” In a passage that effectively invited the court to assess the average musician’s skill level, he argued that the change “is not [attended] with the slightest difficulty & is susceptible of being accomplished by any person able to transpose music in a very short space of time.”[125]

A second declaration came from Johann Munck, the composer and bandleader, whose rendition of the polka the Jaques had advertised on their sheet music, shown below in Figure 2. Like Curtis, Munck stated that “Loder has made no change in the melody whatever and has added no original matter to the composition and has made no new combination of the materials of said original air but has merely adapted the old melody to the piano-forte.”[126] Munck explained that before the lawsuit, he had neither heard Loder’s theatrical performance nor seen Jollie’s sheet music. Why, then, was his arrangement also entitled The Serious Family Polka? According to Munck, it was because a clerk in a music shop had asked him to arrange a piano version of a popular song he had heard at a party. The clerk didn’t know what it was called, only the name of the theater at which had been performed. After a failed attempt to get the clerk to whistle the tune, Munck headed to the theater and asked the musicians there, who identified the piece as the German Röschen Polka. After learning that the piece accompanied the production of The Serious Family, he and the store clerk “jokingly baptized it ‘The Serious Family Polka.’”[127] Although Munck couldn’t convince that particular store to buy the rights to his arrangement, eventually the Jaques brothers did.[128]

Fig. 2: Cover page to the Jaques Brothers’ sheet music for Serious Family Polka[129]

On September 30, 1850,[130] Nelson issued a decision deeply skeptical of the plaintiff’s claim. Perhaps reacting to the witness testimony that Loder’s work must have been easy to do, Nelson reasoned that copyright did not protect “slight and unimportant variations, which any person of ordinary skill and experience in music could have made.”[131] A mere adaptation of an existing melody was categorically insufficient, he wrote, because “[t]he original air requires genius for its construction; but a mere mechanic in music . . . can make the adaptation or accompaniment.”[132] Original additions to, or adaptations of, preexisting material didn’t deserve protection so long as they were the kind that “a writer of music with experience and skill might readily make.”[133]

Unable to determine as a factual matter whether the plaintiff’s work met that standard on the record before him, Nelson suspended decision on the injunction motion and referred the matter to be tried before a jury (“direct[ed] an issue at law” in the parlance of equity courts).[134] No further proceedings took place, however. On December 11, the parties filed their consent to discontinue the case.[135]

The Jollie theory that only works of romantic “genius” merit protection, while quotidian products of everyday “mechanics” do not, was radical. Anachronistically, of course, it looks nothing like modern copyright’s “minimal degree” standard for protectable creativity under Feist. More to the historical point, though, it also looks nothing like Justice Story’s vision of humdrum, incremental originality that by that point had been percolating for over a decade. Jollie represented a fundamentally different vision of copyrightable authorship.[136]

From what legal authority did Nelson draw this alternative vision? According to the reported opinion, the defendants relied principally on a British precedent from fifteen years earlier, D’Almaine v. Boosey.[137] That case would turn out to be all they needed. D’Almaine was the only authority on copyrightability that Nelson cited.[138] But in doing so, he made a larger doctrinal leap than he let on. D’Almaine wasn’t a case about copyrightability thresholds at all. It was, instead, about the scope of the fair abridgement defense to an infringement claim (the precursor to the modern fair use doctrine).

The dispute in D’Almaine concerned a music publisher that had rearranged arias from the 1834 opera Lestocq as instrumental dance music.[139] When the rightsowner sued, the defendant invoked the fair abridgment doctrine that immunized otherwise-infringing copies because, as an earlier case put it, “the invention, learning, and judgment of the [secondary] author is shewn in them.”[140] The D’Almaine case record reveals that many of the parties’ filings focused on the level of authorial skill necessary to execute a successful dance arrangement. Two composers each submitted an affidavit on behalf of the defendant arguing that the arrangements at issue required “a very considerable degree of musical skill and talent,” and that the commercial value of the music “is very much increased or diminished by the talent and ability of the composer or arranger of the said music so composed arranged altered or added to for the purpose of being danced to.”[141] In an analogy straight out of the fair abridgment case law, the witnesses characterized the defendant’s arrangement as being so different from the underlying arias as to be “equally as distinct as in the instance of two distinct [treatises] upon one and the same subject by different authors in which each Author in his own treatise uses the same [work] as his foundation or from which the author takes his lead but amplifies or enlarges or abridges and explains the subject according to his own ideas.”[142]

The plaintiff, meanwhile, countered with the affidavit of a music professor who opined that “the melodies or airs are the substantial and essential portions of an Opera and the most valuable and important parts thereof.”[143] Opera composer Henry Bishop (today probably best known for his song Home! Sweet Home![144]) also weighed in to declare that composers were customarily compensated not just for full-score reproductions but also for piano/voice arrangements.[145] The common denominator between the various editions was the opera’s melodies, which “constitute the parts of the music of operas most material to the interest of purchasers of the copyright.”[146]

The plaintiff’s argument won. The Court of Exchequer held that the rearrangement did not excuse copying the aria’s tune, for “the subject of music is to be regarded upon very different principles. It is the air or melody which is the invention of the author, and which may in such case be the subject of piracy.”[147] In the line that would inspire Nelson’s reasoning in Jollie, the court reasoned that melody is “that in which the whole meritorious part of the invention consists . . . . The original air requires the aid of genius for its construction, but a mere mechanic in music can make the adaptation or accompaniment.”[148]

Jollie’s mechanic/genius dichotomy thus came straight from D’Almaine’s assessment of the intellectual labor required for musical arrangements. But it amplified that dichotomy in two ways. First, it grafted D’Almaine’s holding— which governed only what a copyist needed to do to avoid infringement—onto the standard for what an author needed to do to secure protection in the first instance.[149] Second, it took a principle that might have been limited to music cases and seemingly stated it as a transsubstantive rule of copyrightability. On its face, D’Almaine could be read narrowly to stand for the proposition that fair abridgement doctrine works differently when the copied material consists of melodic themes rather than literary ones.[150] Indeed, three years before Jollie was decided, that’s precisely how Curtis’s copyright treatise read it. It interpreted D’Almaine as distinguishing between books, where the court “apparently recognize[d] the right of making an abridgment of some kind,” and musical compositions, where it did not.[151] Curtis treated D’Almaine as erecting a form of music exceptionalism based on the premise that music lacks the sort of common stock of ideas that literature possesses:

The distinction which [the D’Almaine court] makes between music and a literary composition seems to be merely that an air or melody in music is the pure invention of the author, and there is no ground of a common subject for a subsequent composer to fall back upon; whereas, in literature, although the particular composition is original, and exclusively the fruit of the author’s mind, the subject is common to all men, and may admit of distinctions between the modes of treating it, which music will not admit of.[152]

Jollie appears to go further. It proposes that the work of a “mere mechanic” simply doesn’t deserve protection, and that the best way to identify those mechanics is to inquire into the average level of skill within the field of practice. Music isn’t the exception; it’s the test case for a broader rule. Taken seriously, then, Jollie would require that authors seeking copyright protection would always need to show that their work surpassed whatever the author’s peers “with experience and skill might readily make.”[153]

B. Patent: Mechanics Versus Inventors

The ordinary mechanic would again play the foil to the romantic creator in Nelson’s companion decision on patentable invention. The patent at issue was granted in 1841 to coinventors John Hotchkiss, John Davenport, and John Quincy for a new type of doorknob.[154] The point of novelty was an improvement in the material out of which the knobs were made. Whereas existing models had been made out of metal or wood, their patent covered “making said knobs of potters’ clay, such as is used in any species of pottery—also of porcelain.”[155]

Fig. 3: Drawings of the knobs from the Hotchkiss Patent (1841)

Had this patent issued under the Patent Act that had governed up through 1835, it would have had a fatal flaw. That version of the statute had contained a provision stating that “simply changing the form or the proportions of any machine, or composition of matter, in any degree, shall not be deemed a discovery.”[156] Under the standard that courts had fashioned to apply that provision, swapping in clay for metal or wood wouldn’t have been patentable unless, by making that swap, “a new effect is produced” whereby “there is not simply a change of form and proportion, but a change of principle also.”[157] Congress repealed that limitation, however, when it passed a revised Act in 1836. As a statutory matter, at least, it seemed in 1841 that the Hotchkiss patent was valid so long as the doorknob was indeed new and useful.

In 1845, the executrix of Hotchkiss’s estate and the other coinventors sued the major Cincinnati industrialist (and soon-to-be Union arms manufacturer) Miles Greenwood, along with his business partner, for infringing the patented knob.[158] Greenwood’s firm was at that time a major iron foundry that supplied hardware items to thousands of homes from Cincinnati westward.[159] The record does not specify what specifically the defendants had done to attract the patentees’ ire. But Greenwood, dubbed by a contemporary biographer the “Tubal-cain of the West,”[160] at least must have provided a big target.

The dispute attracted major legal talent. Initially representing the plaintiffs was Alphonso Taft, who in the 1870s would become the U.S. Secretary of War and then Attorney General. Of particular note to legal historians of intellectual property, he also later represented the defendant in Baker v. Selden,[161] a canonical case on the proper distinction between copyright and patent law.[162] For unknown reasons, Taft’s firm at some point appears to have dropped out of the case. For the duration of the case, the plaintiffs were represented by a “T. Ewing,” possibly fellow Ohioan Thomas Ewing, who had served in the U.S. Senate in the 1830s and had reputedly helped draft the Patent Act of 1836.[163]

The defendants first retained Charles Fox, who would later become a Cincinnati Superior Court Judge.[164] At some point before trial, he was joined by Salmon P. Chase, the future Chief Justice of the United States.[165] Chase took on a number of patent clients during this period, including the defendant in the celebrated and doctrinally foundational case that invalidated part of Samuel Morse’s telegraph patent.[166] When the Hotchkiss case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court, it was Chase who delivered the oral argument.[167]

During the course of the litigation, Greenwood was elected President of the Ohio Mechanics’ Institute.[168] As a card-carrying mechanic himself, it’s perhaps fitting that Greenwood’s defense entirely avoided the “even a mechanic could do it” theory that some other litigants had tried in the 1840s. Instead, the defense was singularly focused on showing that the patentee’s simple substitution of clay for other materials was already anticipated in the prior art. They told the court in 1847 that they had found uses of such knobs in New York, Albany, Philadelphia, and other northeast cities “long before” the patentees’ asserted date of invention.[169] Moreover, they argued, the patentees themselves had known that such knobs had been previously manufactured and sold abroad and “did not believe themselves to be the first inventors.”[170] On the eve of trial the following year, the defendants informed the court that they had unearthed even more anticipating references in the prior art, cataloguing additional uses in Connecticut and dating the public uses of clay and porcelain knobs as far back as 1831.[171]

Supreme Court Justice John McLean presided over a three-day jury trial in Cincinnati in July 1848.[172] After the close of evidence, the plaintiffs requested a jury instruction stating that even if the physical form of their knob had been used before, it remained patentable so long as it had never been attached to clay or porcelain and implementing that attachment “required skill and thought and invention.”[173] If those conditions were satisfied, they contended, then the jury must sustain the validity of any knob “better and cheaper” than the metal and wooden knobs that came before it.[174] But McLean refused. In fact, the plaintiffs’ strategy of highlighting the skill required to attach the knob’s spindle and shank to the clay material may have invited more trouble than they bargained for.[175] The justice reasoned that such attachment may indeed require skill, but merely the kind that “an individual acquainted with mechanics, only, can exercise.”[176] He therefore instructed the jury that if constructing the knob required “no other ingenuity or skill . . . than that of an ordinary mechanic acquainted with the business, the patent is void and the plaintiffs are not entitled to recover.”[177]

These jury instructions are puzzling several times over. First, why did plaintiffs’ counsel not raise Earle, which flatly disapproved of the court’s demotion of mechanical skill?[178] Why, for that matter, didn’t McLean see any need to deal with it either? Why did his instructions ignore the clay knobs allegedly in the prior art, which the defendants had devoted so much evidentiary attention to, and which if proven might have obviated the entire inventiveness issue?[179] And most significantly, given the parties’ singular focus on novelty, why did McLean fashion this “ordinary mechanic” test sua sponte to begin with?[180] Neither the case record nor McLean’s judicial papers suggest any answers. One can only speculate what the court might have done differently had the plaintiffs invoked Story’s precedent.

The plaintiffs appealed to the Supreme Court with a sparse assignment of error declaring simply that the trial court had “erred in the instructions which they gave to the jury.”[181] The Court heard argument over two days in February 1851.[182] According to the summary of the argument included in the reported opinion, the plaintiff focused on the invention’s novelty and utility, again never citing Earle.[183] Chase’s argument for the defense didn’t cite it either.[184] Instead, it focused on substituting new materials and a then-existing doctrine barring patents on new uses for old devices.[185] He asked the Court incredulously if they were really prepared to endorse a system that would allow someone to find the rare object that hadn’t yet been forged in cast-iron—a material that had already been used to make “every thing whose shape can be impressed upon sand”—and then “exclude all other persons from making the same article out of the same material?”[186] The argument didn’t turn on anyone’s ingenuity, nor did it ever reference the trial court’s “ordinary mechanic” standard.

On February 19, about four months after Justice Nelson had issued his copyright decision in Jollie, he ported over the same reasoning to patent law through the Court’s majority opinion affirming McLean’s instructions. “[T]here was no error,” Nelson began, “for unless more ingenuity and skill . . . were required [to apply the shank] to the clay or porcelain knob than were possessed by an ordinary mechanic acquainted with the business, there was an absence of that degree of skill and ingenuity which constitute essential elements of every invention.”[187] These last two words, taken at face value at least, are crucially important. The Court here seemed to announce an element baked into the concept of invention itself, not (as might otherwise be supposed) just into the narrow category of change-of-form cases where the patentee has simply substituted a new material for an old one. Even a new and useful improvement is ineligible for a patent if it is only “the work of the skillful mechanic, not that of the inventor.”[188] Like the genius authors of Jollie, inventors were to be defined in negative relation to the undifferentiated masses of mechanics.

Justice Woodbury dissented. Consistent with his jury instructions in Adams and Edwards, he accused the majority of instituting a patentability standard that “has not the countenance of precedent, either English or American.”[189] He maintained that “the skill necessary to construct” an invention “is an immaterial inquiry.”[190] Unlike every other Justice, he considered the issue settled by Story’s decision in Earle. He would have remanded the case for a new trial before a jury that was properly instructed that, like Earle had held, “a combination, if simple and obvious, yet if entirely new, is patentable.”[191] The majority never engaged that precedent. It simply ignored it.

III. The Two Heightened Thresholds Over Time

Despite what in hindsight seems like a sudden doctrinal shakeup, neither Hotchkiss for patents nor Jollie for copyrights had much of an immediate impact. Each decision’s influence took time to appear. Of course, the nonobviousness regime into which Hotchkiss eventually snowballed dwarfs any copyright change that could fairly be traced to Jollie. Nevertheless, as this Part argues, Jollie’s reverberations continued to be felt in multiple music cases across the twentieth century.

I begin in Section A with a summary of the delayed but eventually exponential growth of nonobviousness after Hotchkiss. As others have already explored this transformation in depth,[192] my review here is brief. In Section B, I then turn, in greater detail, to the comparatively understudied stamp that Jollie has left within its own sphere.

A. What Hotchkiss Did

On its face, Hotchkiss appeared to change patent doctrine immediately. It embedded a new element in the concept of invention. It formally introduced patent law’s version of the reasonable person, the ordinary mechanic (eventually to become known as the person having ordinary skill in the art), to the case law.[193] And most fundamentally, it reoriented the validity test away from the perspective of the businessman and toward that of the scientist.[194]

The case law didn’t feel those effects right away, however. Some early decisions seemed to march in lockstep,[195] but most judges didn’t do much with the case until after the Civil War.[196] Though the twentieth-century Supreme Court saw Hotchkiss as the wellspring of nonobviousness,[197] antebellum judges evidently did not. Even Nelson himself rejected a Hotchkiss-like defense at an infringement trial later that same year.[198] A defendant accused of infringing a patented improvement to a reaping machine argued that the improvement was “so simple and obvious, that the claim, even admitting it to have been new and not before in use, is not the subject of a patent.”[199] Nelson strangely brushed it off, instructing the jury that “[n]ovelty and utility in the improvement seem to be all that the statute requires as a condition to the granting of a patent.”[200] Perhaps Nelson hadn’t truly meant to declare a rule governing all patents (though that’s precisely what he had done) and had instead intended a more limited rule only for cases involving substitution of materials.[201]

In any event, the broader reading of Hotchkiss as a general condition of patentability picked up steam in the 1870s, at a time of growing commercial anxiety over excessive patent litigation.[202] The Supreme Court in 1875’s Reckendorfer v. Faber gave an inventiveness threshold a full-throated endorsement:

An instrument or manufacture which is the result of mechanical skill merely is not patentable. Mechanical skill is one thing: invention is a different thing. Perfection of workmanship, however much it may increase the convenience, extend the use, or diminish expense, is not patentable. The distinction between mechanical skill, with its conveniences and advantages and inventive genius, is recognized in all the cases.[203]

In 1880, the Court followed up with its maxim in Pearce v. Mulford that “all improvement is not invention.”[204] To earn legal protection, the alleged invention “must be the product of some exercise of the inventive faculties” and “involve something more than what is obvious to persons skilled in the art to which it relates.”[205] Most significantly, in 1883’s Atlantic Works v. Brady, the Court cautioned that “[t]o grant to a single party a monopoly of every slight advance made, except where the exercise of invention, somewhat above ordinary mechanical or engineering skill, is distinctly shown, is unjust in principle and injurious in its consequences.”[206] It then poetically detailed those consequences, supplying the Court’s first theoretical justification of its newly expanding inventiveness requirement:

The design of the patent laws is to reward those who make some substantial discovery or invention, which adds to our knowledge and makes a step in advance in the useful arts. Such inventors are worthy of all favor. It was never the object of those laws to grant a monopoly for every trifling device, every shadow of a shade of an idea, which would naturally and spontaneously occur to any skilled mechanic or operator in the ordinary progress of manufactures. Such an indiscriminate creation of exclusive privileges tends rather to obstruct than to stimulate invention. It creates a class of speculative schemers who make it their business to watch the advancing wave of improvement, and gather its foam in the form of patented monopolies, which enable them to lay a heavy tax upon the industry of the country, without contributing anything to the real advancement of the arts. It embarrasses the honest pursuit of business with fears and apprehensions of concealed liens and unknown liabilities to lawsuits and vexatious accountings for profits made in good faith.[207]

By the time William Robinson published his seminal patent treatise in 1890, the Hotchkiss division between invention and mechanical skill had fully taken root. “Inventors,” he wrote, meant only “those by whom creative skill and genius have been exercised. It is the exercise of this creative skill alone which is here recognized as an inventive act, and only the result of such an act, so far perfected as to be available for public use, is an invention.”[208]

Nonobviousness would take a circuitous road through the twentieth century as courts, and eventually Congress, tried to pin down what exactly the concept ought to be measuring. In 1941, the Court infamously raised the bar to the point that even an invention requiring some “ingenuity” would still fall short if that ingenuity amounted to “no more than that to be expected of a mechanic skilled in the art.”[209] The Court wanted to reserve patents for inventions that “reveal[ed] the flash of creative genius.”[210] But identifying which inventions displayed such genius, as opposed to the incremental but still laborious advances through which science typically progresses, proved to be a frustrating task. Judge Learned Hand soon bemoaned this interpretation of Hotchkiss as requiring the search for something “as fugitive, impalpable, wayward, and vague a phantom as exists in the whole paraphernalia of legal concepts.”[211] Congress abrogated that precedent in 1952, when the newly enacted Patent Act finally took the search for “genius” out of the standard and replaced it with the nonobviousness standard still found today in § 103.[212] I won’t wade through the particulars of this more recent history here, but by the time the Court got around to construing the statutory codification of nonobviousness, it identified Hotchkiss as its source.[213]

B. What Jollie Did

Unlike Hotchkiss, still cited by the Supreme Court and regularly taught in law-school patent courses, Jollie isn’t a household case name. Westlaw and Lexis together tally only six judicial citations to Jollie since 1900 (though that number is in fact underinclusive, as both services omit some important ones discussed here).[214] Contemporary treatises have almost nothing to say about it. Nimmer, for example, omits Jollie entirely. Goldstein’s treatise cites it only once, and not for anything to do with its radical originality standard but instead for the banal proposition that courts may admit expert testimony on originality.[215] Most nineteenth-century treatise writers gave Jollie similarly short shrift.[216] Historians know Jollie as an anomaly, the exception that proves copyright’s rule of a low-creativity bar to protectability.[217]

Yet Jollie in fact has a lot more to teach contemporary legal audiences than appearances might let on. While it failed to raise the originality threshold for most classes of subject matter, it nevertheless launched a line of cases that silently raised that threshold when the dispute concerned musical arrangements.[218] Just as Curtis’s 1847 treatise understood D’Almaine to announce a music-specific infringement standard, later cases have implicitly understood Jollie to announce a music-specific originality standard. But these cases almost never state openly that music disputes operate differently. That message is written only between the lines.[219]

Jollie’s effects took decades to materialize. It did receive an approving nod in Daly v. Palmer,[220] an 1868 case that, like D’Almaine, was focused on the standard for nonliteral infringement. Other than that, though, judges in the second half of the nineteenth century didn’t cite Jollie in published opinions for anything to do with copyright scope. On the few occasions during this period when courts did invoke the case, it was for a different proposition, such as the unavailability of copyright protection for a work’s title.[221]

In fact, the next time a case actually teed up a similar question of originality for musical arrangements, the court not only failed to cite Jollie but also contradicted it. Carte v. Evans,[222] an 1886 decision enjoining an unauthorized piano arrangement of The Mikado’s orchestral score, declared that such arrangements “require[d] musical taste and skill of a high order.”[223] The court reasoned that “[n]o two arrangers, acting independently, and working from the same original, would do the work in the same way, or would be likely to produce the same results, except so far as they might both resemble the original.”[224] The capabilities of ordinary musicians wasn’t the court’s touchstone for originality. Instead, it was the likelihood that musicians could make different choices about how to solve the same problem—a test that sounds much like the modern Feist standard and nothing like Justice Nelson’s.

Yet in the twentieth century, Jollie was given a second life. The person most responsible for putting it back on the jurisprudential map was a man named Joseph James. James was a lawyer, a composer, and at one point the mayor of Douglasville, Georgia.[225] He was also a founder and leader of the United Sacred Harp Musical Association, an organization devoted to preserving the Christian hymnody tradition known as Sacred Harp singing. The movement, which took its name from Benjamin Franklin White’s 1844 hymnal The Sacred Harp, had by the beginning of the century spread throughout the rural South.[226]

White, the original compiler of the hymnal, died in 1879.[227] James’s role in the development of copyright doctrine was rooted in a dynastic struggle over who would succeed White as the steward of the hymnal’s authoritative edition. In 1902, after the copyright in the previous incarnation of the hymnal had expired, Wilson Marian Cooper published a new version that quickly gained popularity in his native Alabama.[228] Almost all earlier versions had been written for three voices: treble, tenor, and bass. Cooper’s edition supplied a fourth voice part, an alto, that injected an additional inner harmony into the chords. Cooper’s revision had been the first significant one in decades, and the choice to employ four- rather than three-part harmony was a genuine innovation in the genre.[229]

To many in the Sacred Harp movement, however, Cooper was an outsider.[230] Probably motivated by Cooper’s success but unwilling to adopt his version, James’s United Association decided to put out its own revision.[231] That new revision appeared as The Original Sacred Harp in 1911.[232] Like Cooper’s, the James edition uniformly included an alto line in its hymns. It would eventually become a great success, subsequently folded into an edition that would become the most widely used Sacred Harp hymnal of the twentieth century.[233]

Despite that ultimate success, however, the James edition began in controversy. First, the son of the original 1844 compiler formed a secession movement when the United Association adopted James’s revision over his competing one.[234] In news that made the front page of Atlanta’s leading paper, that son protested, “The book which has been adopted and which is promulgated by President James, is a clear infringement on the original song book published by my father, and contains practically all the songs which he incorporated in his book.”[235] Despite the incendiary of language of infringement, though, there’s no indication that he brought any legal action against James.

Cooper, by contrast, was more litigious. In 1913, James advertised a “Great Singing Convention” in Atlanta for the United Association’s annual session. As shown in the advertisement reproduced below in Figure 4, he billed it as “the largest gathering of vocalists ever assembled in the Southern States.”[236]

Fig. 4: Advertisement for Joseph James’s Sacred Harp Singing Convention

Cooper had evidently seen enough. He brought an infringement claim alleging that James had copied his “arrangements, adaptations and altos.”[237] Composing a new alto line for each of the songs, Cooper urged, had been a serious undertaking that had greatly improved the underlying three-part versions.[238] According to Cooper, James had simply taken his alto parts and inserted them into his hymnal edition rather than come up with his own.

James mostly handled his own defense. In a letter to the court at the outset of litigation, he painted Cooper’s lawsuit as a vexatious attempt to interfere with the upcoming convention. He asked for an opportunity to be heard before any restraining order was entered.[239] The court moved quickly, but not nearly that quickly. On September 12, the date that the singing convention was to begin, it set a hearing for about two weeks out.[240] It’s not clear whether the event in fact took place. In any case, when the hearing date appeared, James was a no-show.

After a month had passed, James reappeared. He explained that he had been ill and, according to his physician, had “suffered from a nervous breakdown from over-work.”[241] Nevertheless, he wasn’t about to hand off his defense to another attorney, even though he was nominally working with a cocounsel. “[T]he very nature of said case,” he wrote, “requires petitioner’s personal attention . . . [N]obody understands the facts necessary to file this answer but the defendant . . . .”[242] With James back in the picture and evidently running the operation, the court lifted the restraining order.

James’s litigation strategy was to paint the composition of the alto line as yeoman’s work. It was a gambit that relied entirely on Jollie. How creative Cooper’s new inner harmony actually was is at least debatable as a question of fact.[243] But under Justice Story’s low-originality threshold that had supposedly won out over Justice Nelson’s requirement of musical genius, it’s far from obvious that the answer would have even mattered. So long as Cooper had exercised genuine intellectual labor in choosing a vocal part that the surrounding voice leading didn’t already dictate, the works should have been protected.

Jollie, however, directed otherwise. The first page in the Cooper case file is an undated and seemingly freestanding list of authorities, “As to Right to Original Copyright.” And the first such authority listed was Jollie’s admonition that copyright protection should be unavailable to whatever a “writer of music with experience and skill might readily make.”[244] It’s not clear whether the document was prepared by James or by the court itself, but either way it conforms perfectly to James’s theory of the case: that anyone of even modest musical ability could have composed the alto line.

In a set of interrogatories filed with the court, also untitled and undated, a witness answered a simple “yes” when asked whether the alto part constituted “an addition which a musician of experience and skill, though not an original composer, could readily make.”[245] Another interrogatory asked, “Does it necessarily require a person talented in composition to write an alto?” The witnesses responded that “[i]t would not require originality, but to be correct would require training.”[246] Given the question’s design to provide a Jollie-ready answer, it seems likely that the individual providing the answer was James’s witness.[247]

In March 1914, James moved to dismiss the complaint in a brief that he signed as counsel. Jollie, he argued, compelled that result.[248] He didn’t mince words. “An alto,” he declared, “is absolutely nothing and would be of no value whatever to anybody without the balance of the tune . . . . It is not original, it is nothing.”[249] He mocked Cooper as

an egotist, that knows nothing about music so as to be a composer of any ability, that thinks that he can take other peoples [sic] works on which the copyright has expired and appropriate to his own use in a book and put his picture in it and take out a good many of the tunes and put others in the places and claim that he has a copyright.[250]

It worked. The court dismissed the case for want of originality, leading with “the rule laid down by Mr. Justice Nelson” that copyright does not extend to what a “‘writer of music with experience and skill might readily make.’”[251] Cooper’s alto lines, the court concluded, failed that test. “[W]hile probably made by musicians of experience and some skill,” the new voice parts were “not necessarily the productions of persons having the gift of originality in the composition of music. An alto may be an improvement to a song to some extent, and probably is; but it can hardly be said to be an original composition, at least in the sense of the copyright law.”[252]

That this standard sounded patent-like wasn’t lost on the court. It made the connection explicit: “In patents we say that any improvement which a good mechanic could make is not the subject of a patent, so in music it may be said that anything which a fairly good musician can make, the same old tune being preserved, could not be the subject of a copyright.”[253] Despite the nonchalance with which the court made this analogy, it remains an extraordinary doctrinal move. In the early twentieth century, no one had yet explicitly tied the Hotchkiss inventiveness standard to copyright’s originality requirement. Perhaps as a result, the court hedged on how far its prescription could go. Its holding doesn’t purport to extend to all copyright subject matter but instead only to music.

Three years later, a treatise writer would pick up on this subject-matter selectivity. William Benjamin Hale, the author of the copyright treatise that formed a volume of the legal encyclopedia Corpus Juris, wrote that musical arrangements needed to leap a double hurdle in order to obtain protection. First, as with any copyrightable subject, the composition “must be original, within the meaning of originality as elsewhere explained.”[254] But, citing both Jollie and Cooper, the treatise added Nelson’s further requirement that the work must display more than mere mechanical skill. Picking up right where Cooper had left off, it posited that “[t]he distinction is substantially that made in the law of patents between the exercise of inventive genius and the exercise of mere mechanical skill; the former is protected by the statute, but the latter is not.”[255]

Modern practitioners wouldn’t recognize that proposition. There is no doctrinal first principle that supports a more patent-like protectability threshold for musical works than for other works. But Jollie was a music case, and the Cooper court didn’t need anything more than a music case to reach its preferred outcome. By 1920, then, judges had a fledgling line of authority concluding that patent’s standard of invention was a reasonable fit for music copyright.

That authority would be invoked sporadically, appearing only a handful of times over the remaining decades of the twentieth century. But even its few citations were prominent enough to reinforce the notion that musical originality should be slotted on a different analytical track than other kinds. In Norden v. Oliver Ditson Co.,[256] the work-in-suit was an English-language adaptation of a Russian hymn that had required rhythmic changes to compensate for the new words’ syllabification. On the strength of Jollie and Cooper, the court held that the piece was ineligible for protection. Works of visual art, the court deduced, “need not, like patents, disclose the originality of invention, but may present an old theme if there is distinguishable variation.”[257] Musical works, by contrast, were to be judged by Cooper’s “fairly good musician” standard. Copyright wasn’t available for the English-language arrangement because it “remained ‘the same old tune,’” whose changes “any skilled musician might make.”[258]

Similarly, in Arnstein v. Edward B. Marks Music Corp.,[259] the court announced that when assessing the copyrightability of musical arrangements, “the same test is to be applied as in the case of patents; that is, it must indicate an exercise of inventive genius as distinguished from mere mechanical skill or change.”[260] Unlike the works involved in earlier cases that had invoked Nelson’s standard, the pop song at issue in Arnstein was a new piece rather than a new arrangement of a preexisting one. Perhaps as a result, the court deemed it to be sufficiently inventive to pass that high bar.[261] Along the way, though, the court signaled how little it thought of the authorship involved in these mass-culture products, writing that neither the plaintiff’s nor the defendant’s music was a “work of great merit.”[262] They were, rather, “popular songs of the kind that have a limited vogue and soon pass into the great limbo of forgotten songs, never to be resurrected.”[263]

By this point, Jollie’s limited progeny had become recognizable as its own line of originality doctrine. In a 1941 report to Congress, for example, the Register of Copyrights wrote that courts held the power to “den[y] the validity of a claim of copyright based on an alleged authorship where that authorship was found to be lacking.”[264] This is an unextraordinary assertion, so far as it goes, but the Register’s best authority for that proposition was a single string cite of four cases: Jollie, Norden, Cooper, and Arnstein.[265] To the Register, apparently, those cases most clearly represented what the absence of originality looked like.

Similarly, when Zechariah Chafee wrote his famous Reflections on the Law of Copyright in 1945,[266] the move toward patents had become familiar enough for him to endorse it as a bedrock principle. After quoting “Judge Nelson’s test,” Chafee observed that music copyright operated by “an analogy to the rule which refuses to patent an improvement on an existing invention, if any good mechanic could think up the improvement.”[267] To Chafee, the analogy was meant to ensure that merely minimal additions didn’t prevent what today we might call evergreening of protection for expressive works.[268] That goal, of course, is a familiar one. It’s shared by most contemporary commentators and reflected in judges’ regular insistence that derivative works be readily distinguishable from their underlying originals.[269] But tying the bar for sufficient additions to what “any good mechanic could think up” remains a fundamental break from the rest of the generally applicable originality standard. Whereas a derivative in other fields might be able to skate past so long as it was distinguishable enough from the original work, a musical derivative would also need to differentiate itself from the universe of other potential derivatives that persons having skill in the art were likely to produce.

Despite Chafee’s imprimatur, however, over the remaining thirty years before Congress would pass the current Copyright Act, only one case would rely on the Jollie standard, McIntyre v. Double-A Music Corp. in 1958.[270] And between the Copyright Act’s passage and the Supreme Court’s 1991 Feist decision clarifying originality doctrine’s low-creativity threshold, no case relied on it. An observer in the early 1990s could have reasonably guessed that Nelson’s high-creativity threshold had simply died out.