Social Justice Conflicts in Public Law

“Social justice” is everywhere in public law. Scholars and activists are calling for racial justice, climate justice, and health justice, among other claims. When commentators speak about multiple different social justice claims, it is often through an intersectional lens that views these claims as co-constitutive with one another, such as, “There is no climate justice without racial justice.” These justice claims are important and long overdue.

But conflicts between different social justice claims—what this Article calls “justice conflicts”—are inevitable in policymaking. Justice conflicts occur when the multiple social justice claims involved in a policy issue point to opposing outcomes. The Biden Administration prioritized social justice and began to address how agencies should evaluate various social justice claims in policymaking. While an exciting first step, its initial actions did not give clear guidance to agencies and other institutions. As a result, political institutions often resolve justice conflicts through non-transparent political decisions, which ultimately harm affected political communities.

This Article argues that political institutions should embrace “mid-level justice principles” to analyze justice conflicts. Mid-level justice principles are justice principles that apply across different policy areas and provide standing moral reasons to justify certain policy outcomes. Until now, public law has mostly embraced only procedural justice principles, such as consultation requirements and regulatory impact analyses. While helpful, these procedural measures do not provide substantive guidance about how to actually resolve justice conflicts. Mid-level justice principles fill this gap.

While political institutions have implicitly adopted some mid-level justice principles in an uneven fashion, this Article provides avenues for Congress, the President, and agencies to explicitly and consistently institutionalize mid-level justice principles. These proposals will improve policymaking and provide a mechanism to transparently analyze nonquantifiable normative values, which has thus far perplexed regulators, as well as both proponents and skeptics of cost-benefit analysis. While the Supreme Court has increasingly inserted itself as the institutional arbiter of social justice claims, the Court’s assertion of its primacy to evaluate justice conflicts should be resisted on democratic and epistemic grounds. Instead, “democratic policymaking,” which occurs via Congress, the President, and administrative agencies, should be the primary site to resolve justice conflicts in our society.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

In the early 2000s, the Navajo Nation petitioned the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for an air quality permit needed to build a new coal power plant in northeast Arizona.[1] The Clean Air Act (CAA) treats Native nations similar to states, so the EPA has authority to review any petition from Native nations for new pollution sources to ensure they fall within CAA emission standards.[2] The Navajo historically rely on coal for economic resources. Currently, the mining, production, and use of coal accounts for 42 percent of revenue in the Navajo Nation’s General Fund.[3] The Navajo have also historically embraced their coal resources to promote their own sovereignty within the overarching colonial and capitalist structures they have been subjected to for most of America’s history.[4] Coal-related economic activity provides thousands of well-paying jobs for Navajo members living on or near their reservation,[5] which has a 48.5 percent unemployment rate.[6] Navajo political leaders argued that the new plant, called Desert Rock, would serve a vital role in stabilizing their economy given plans to phase out existing power plants in the coming decades.[7]

In July 2008, the Bush Administration’s EPA approved the Nation’s air-quality permit for Desert Rock.[8] The State of New Mexico and environmental groups, including Earthjustice, appealed the EPA’s approval, arguing the EPA failed to perform certain procedural requirements, including consulting with other agencies and considering how the plant would affect nearby national parks.[9] In early 2009, the EPA, now under the Obama Administration, announced that it would reconsider the permit, and then later reversed and withdrew the permit.[10] Desert Rock’s fate then sat in limbo while the EPA, states, environmental groups, and the Navajo Nation continued to debate its merits. Desert Rock was finally cancelled in March 2011.[11] The Navajo Nation, EPA, and environmental groups have continued to clash in recent years as the Navajo have sought to construct new pollution sources and upgrade existing sources related to their coal activities.[12]

If one was a well-meaning EPA Administrator who cared about social justice, how should they have decided the Navajo Nation’s pollution permit for Desert Rock? On one hand, the new plant would provide vital economic resources to the Nation and its citizens, who have long suffered from corporate mistreatment, racism, and colonial practices,[13] as well as promote the Nation’s self-determination in setting its own socioeconomic policies.[14] On the other hand, as the effects of climate change become more pronounced, a massive new coal plant would only exacerbate local and national issues related to climate change.[15]

The Nation’s permit saga raised multiple distinct types of social justice claims, including racial, economic, environmental, energy, and climate justice. In philosophical literature, each of these justice claims, such as racial justice or environmental justice, is known as an “applied justice” claim because the claim of what a group is owed is restricted to a specific policy domain.[16] For example, environmental justice pertains to the demands of justice only within the domain of environmental policy. In recent years, scholars and activists have created a number of different types of various applied justice claims. It is now commonplace to see calls for racial, gender, reproductive, economic, labor, health, environmental, climate, energy, and disability justice, among other applied justice claims.[17]

The Desert Rock example illustrates that specific policy issues can involve multiple applied justice claims. As scholars pointed out early in the environmental justice movement, environmental policy often concerns issues of racial justice, gender justice, and economic justice, among other claims.[18] When scholars and activists speak about policy issues that pertain to multiple applied justice claims, it is often through an intersectional lens that views the different applied justice claims as congruent with one another.[19] This intersectional lens is typified by phrases such as, “There is no climate justice without racial justice,”[20] or “There is no economic justice without reproductive justice.”[21] These applied justice and intersectional claims are overdue and necessary given that law has long silenced the claims of underrepresented groups and ignored the systemic methods by which such silence actively harms them.[22]

But “justice conflicts” between these different applied justice claims are inevitable during policymaking on concrete policy issues. Justice conflicts arise when the various social justice claims involved in a policy issue point towards conflicting policy outcomes.[23] In the Desert Rock example, the permit acquisition process pitted racial and economic justice, which pointed towards granting the permit, against climate, environmental, and energy justice, which pointed towards denying the permit.[24] While scholars have recently mentioned the possibility of tension among social justice claims, few have attempted to evaluate the nature of the conflict in question or pose a framework to solve such conflicts.[25] Some scholars who have pointed out the potential for such tension have invited future theorizing regarding how to resolve such conflicts in policymaking.[26] This Article accepts that invitation.

This Article opens a conversation on whether there are principles of justice that public law can apply when grappling with how to resolve justice conflicts. In the wake of John Rawls publishing his groundbreaking A Theory of Justice in 1971,[27] public law scholars spent the next few decades trying to institutionalize “basic justice” principles, which attempt to establish the overall structures to distribute goods, benefits, or services within society.[28] As opposed to applied justice principles, which cover only one policy area, basic justice principles attempt to cover the entirety of social justice itself. However, given increased levels of moral pluralism and political polarization in America, by the end of the twentieth century, many scholars no longer believed that a consensus on basic justice principles was possible.[29]

Instead, public law largely embraced procedure over substance to grapple with normative values in policymaking.[30] Prominent examples include the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA),[31] the Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA),[32] Executive Order 12,866,[33] and the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) itself,[34] among others.[35] While procedural requirements improve policymaking,[36] they give policymakers little guidance on how they should consider substantive normative values that cannot be fully quantified, such as social justice.[37] As a result, many administrative agencies are hesitant to openly embrace such normative values. Instead, they opt to downplay their role in agency decision-making and cover their bases on technical reasoning and cost-benefit analysis (CBA).[38]

While the Biden Administration made major strides to address the lack of guidelines concerning nonquantifiable normative values in policymaking,[39] the Administration’s steps were tentative and permissive by focusing on agency process. As a result, agencies continue to lack guidance on how to actually include substantive values in policymaking.[40] Capitalizing on the prior Administration’s insistence that agencies modernize regulatory analysis,[41] the growing importance of social justice in scholarship and activism, and the widespread nature of social justice conflicts in policymaking, now is the time for scholars to provide solutions for resolving justice conflicts.

This Article argues it is possible and desirable for public law to embrace substantive justice principles to evaluate and help resolve justice conflicts. To make this argument, it identifies the conceptual category of “mid-level justice principles” within the concept of justice. Mid-level justice principles are trans-substantive principles of justice that provide standing reasons to justify certain policy outcomes. Mid-level justice principles are trans-substantive because they cover multiple policy areas (and are therefore broader than applied justice principles), but they do not fundamentally structure all justice claims in society (and are therefore narrower than basic justice principles).[42] The existence of mid-level justice principles is occasionally assumed in public law, but their properties have not been examined, nor have there been attempts to explicitly institutionalize them.[43] Examples of well-known principles in public law that are actually mid-level justice principles include procedural justice, anti-domination, capabilities theory, and restorative justice.[44] In fact, CBA itself is a mid-level justice principle. However, as currently structured, CBA suffers from multiple well-known shortcomings when policy issues involve normative values that resist quantification.[45]

The primary purpose of this Article is to determine whether public law can develop a principled framework to resolve justice conflicts and which political institutions should have the power to resolve them. In furtherance of this purpose, this Article articulates the category of mid-level justice principles and demonstrates how current and future political institutions, including presidential administrations, can use them to analyze policy involving social justice that resists quantification, such as with justice conflicts.[46] Adopting mid-level justice principles provides a consistent and principled mechanism for political institutions to qualitatively analyze important normative values, such as social justice. The Article also argues that institutions adopt and prioritize one particular mid-level justice principle, egalitarian reparative justice, due to its importance in rectifying past governmental harms and substantiating political equality in our democratic government. In the case of Desert Rock, this reparative justice principle creates strong pro tanto reasons that the EPA should have granted the Navajo Nation’s permit, despite its harms to the climate.[47]

The current alternative to institutions adopting mid-level justice principles is the status quo, whereby institutions will continue to be without guidance on how to evaluate justice conflicts. This situation means that agencies will have to internally debate whether to adopt substantive justice principles on a case-by-case basis. This alternative is problematic for numerous reasons, including the lack of transparency to affected persons and reviewing courts, interagency variability, and the continued influence of well-funded interest groups in policymaking.

Multiple political institutions can adopt mid-level justice principles.[48] While drafting statutes, Congress can increase statutory specificity concerning which mid-level principles agencies should prioritize when promulgating regulations to implement the statute in question. In addition to providing improved guidance to agencies and explicitly communicating the importance of social justice, increased statutory specificity should also ameliorate current Supreme Court concerns that animate their expanded use of the major questions doctrine. Meanwhile, the President can coordinate and prioritize implementing mid-level justice principles.

However, due to congressional gridlock, the limits of top-down presidentialism on matters of regulatory experimentation,[49] and the vacillation between presidential administrations in caring about social justice, agencies will likely serve as the primary institution to substantiate mid-level justice principles. Given the experimental nature of structuring mid-level justice principles into policymaking, agencies should first utilize informal guidance to structure mid-level justice principles and then use stickier rules once they have settled on their best practices.[50]

Importantly, agencies institutionalizing mid-level justice principles as guidance or rules provides a structured mechanism for agencies to analyze normative values that resist quantification during regulatory review. This feature of mid-level justice principles should be appealing to both CBA proponents and detractors because it provides a principled framework to qualitatively analyze normative values that have been difficult to integrate into CBA.[51]

Despite the importance of social justice in congressional, executive, and agency policymaking, the Supreme Court has recently tried to claim primacy over social justice issues. Over the past few terms, the Supreme Court has expanded its imprint across public law, including augmenting presidential removal powers,[52] revisiting the constitutional status of abortions[53] and affirmative action programs,[54] expanding the major questions doctrine,[55] and removing judicial deference to agency interpretations.[56] In doing so, the Court has inserted itself as not only the decider of which other institution should resolve justice conflicts, but has also increasingly determined that the Court itself should arbitrate justice conflicts. This move should be resisted for those who care about institutionalizing social justice given the Court’s historic hostility to many social justice claims,[57] as well as lingering democratic and epistemic concerns regarding the Court. Instead, what this Article calls “democratic policymaking”—which occurs via Congress, the President, and administrative agencies—should reclaim its place as the primary site to resolve justice conflicts in our society.

This Article proceeds as follows. Part I traces the recent proliferation of applied social justice and intersectional justice claims in public law. It then introduces the problem of justice conflicts and provides historical and contemporary examples of justice conflicts. The Part ends by discussing how policymakers can distinguish genuine justice conflicts from “illusory justice conflicts,” which are false justice dichotomies generated by social justice opponents for strategic political and jurisprudential purposes.

Part II describes the three different conceptual levels at which principles of justice can operate—applied, mid-level, and basic. The Part then describes how public law has abandoned the project of seeking substantive basic justice principles and has instead focused on procedural justice principles. While helpful, this procedural focus has left agencies without guidance on how to utilize substantive justice principles. The notable exception here is CBA, but it suffers from well-known problems when policy issues involve normative values that escape full quantification. This Part then critically engages with the Biden Administration’s actions to improve normative evaluation in policymaking. While laudable, the permissive and general nature of their actions still left agencies without substantive guidance to integrate social justice principles into policymaking. This Part ends by proposing one attractive way that this can be done—political institutions should embrace substantive mid-level justice principles as standing default rules for future policymaking.

Part III provides ways for Congress, the President, and agencies to institutionalize substantive mid-level justice principles. The Part ends by arguing that the Supreme Court’s power grab to arbitrate justice conflicts should be concerning for those who care about institutionalizing social justice claims given the Court’s historic hostility to such claims. The Court’s increased power to resolve justice conflicts should also be normatively resisted given the comparative democratic and epistemic weaknesses of judicial policymaking compared to the dialogic and iterative nature of democratic policymaking between Congress, the President, and agencies.

Before progressing, a few caveats and explanations are necessary. First, this Article was written in a generative spirit to help identify mechanisms for those concerned with social justice to translate important social justice claims into concrete policies. Therefore, it is meant to provide guidance to well-meaning policymakers who are concerned with promoting social justice but are not sure how to translate their general concerns into concrete policy.[58]

Further, this Article is meant to open a conversation about a phenomenon that is widespread in local, state, and federal policymaking but has thus far escaped examination. Moreover, it was written recognizing that it will hopefully open a conversation, rather than purport to end one. Relatedly, it is an interdisciplinary project that touches on multiple disciplines with their own conversations about social justice. Given this interdisciplinary nature, the Article’s primary purpose is to advance an overarching framework for examining justice conflicts that creates analytical space for others to push the conversation forward regarding their preferred substantive theories of social justice. Finally, this Article operates with the assumption of taking social justice scholars and activists at face value that their claims are ones regarding the content of justice as a normative concept.[59]

I. Social Justice Claims in Public Law

Recently, there has been a proliferation of social justice claims in law and policy. Some of these calls for social justice occur in isolation—“Climate justice now!”[60] However, many scholars and activists adopt an intersectional lens to argue that different social justice claims must be achieved together. For example, many women’s groups now proclaim, “There is no reproductive justice without racial justice.”[61] Indeed, some commentators argue that different social justice claims must be related to other ones at a conceptual level.[62]

But it’s not always the case that these different social justice claims will run together to support the same policy outcome. Sometimes, the various social justice claims implicated by a policy issue will create justice conflicts. While public law scholars concerned with social justice have occasionally mentioned the possibility of such conflict, few have described or evaluated the nature of these conflicts.[63] However, these justice conflicts are unavoidable as abstract claims for social justice are concretized during policymaking. This Part traces the rise of social justice claims in public law and analyzes when policy issues create justice conflicts.

A. The Proliferation of Social Justice Claims in Public Law

Social justice claims are not new. Martin Luther King, Jr.,[64] President Lyndon B. Johnson,[65] and racial equality advocates[66] adopted the language of racial justice throughout their fight for civil rights and racial equality in the mid-twentieth century. In the late 1960s, Justice Thurgood Marshall evoked the language of racial justice in a series of speeches to commemorate the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment.[67] By the early 1970s, the language of racial justice began to percolate in law,[68] history,[69] and sociology,[70] among other academic disciplines. Calls for economic justice have an even older lineage going back to early twentieth-century social reformers.[71] Gender justice claims soon followed in the second half of the 1980s.[72] By the end of the 1990s, law had become immersed with claims for gender and reproductive justice.[73]

Many activists and scholars have also adopted a social justice framework without explicitly adopting the language of “social justice.” This situation occurred in the nascent environmental justice community during grassroots protests against corporate dumping in minority communities in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[74] Meanwhile, law scholars lagged behind activists, not embracing the concept of environmental justice until the late 1980s and early 1990s.[75]

Over the past ten to fifteen years, the types of social justice claims made in legal scholarship and activism have proliferated. Climate justice entered public law around roughly 2008–2010,[76] energy justice arrived in the first half of the 2010s,[77] and health justice was first used around 2014–2015.[78] In recent years, discussions of disability justice,[79] just transitions,[80] and coastal justice,[81] among other new types of social justice claims have also sprouted up.

The frequency of social justice in legal scholarship has also increased. For example, references to gender justice went from averaging around twenty mentions per year in the mid-2000s, to around seventy in the mid-2010s, to 145 annual mentions over the past three years.[82] The increase is more pronounced for newer types of social justice claims. For climate justice, usage increased from the single digits in the mid-2000s to averaging ninety-four mentions per year over the last three years.[83] Similar patterns of increased usage apply to many types of social justice.[84]

B. Intersectional Social Justice Claims

Given the proliferation of social justice claims within legal scholarship, analyzing how these claims actually interact in policymaking has become increasingly pertinent. More and more, social justice claims are being understood through an intersectional lens. Intersectionality theory was developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw in a series of pathbreaking articles in 1989 and 1991.[85] First described as a metaphor[86] and then a “provisional concept,”[87] Crenshaw used the concept of intersectionality to explain the inadequacies of existing legal categories, which atomized different forms of oppression that could actually overlap among groups.[88] While Crenshaw focused on explaining how neither racial nor gender discrimination claims adequately addressed the unique harms experienced by Black women in America,[89] she recognized such oppression likely applied to other groups as well.[90]

In the following decades, intersectionality became nearly synonymous with social justice.[91] Scholars and activists who work in many different types of social justice explicitly state that they use an intersectional approach to analyze policy issues that involve their social justice claims.[92]

Within legal scholarship, claims regarding the intersectionality of social justice claims are often made in two different ways. For the first kind of claim, which I call the internal account, a commentator will state that a specific social justice claim encompasses other social justice claims as well. For example, some environmental and energy justice advocates say that the concept includes climate justice, racial justice, and gender justice, among others.[93] For the internal claim, the specific social justice claim is intersectional because it includes the other types of social justice claims.

For the second kind of claim, which I call the external account, the commentator will claim that a specific social justice claim cannot be achieved without another social justice claim also being achieved. Take, for example, the popular statement in the reproductive justice community, “There is no reproductive justice without racial justice.” Framed in this manner, racial justice does not become a component of reproductive justice, but rather their fates run together because they are theoretically inextricable.

The correctness or coherence of the internal or external account is beyond the scope of this Article.[94] Rather, this Article is interested in the fact that on both accounts, the different social justice claims are either definitionally intertwined with each other (internal account) or run together (external account). Both accounts describe the various social justice claims as agreeing with one another or pointing in the same direction as to the desired policy objectives and outcomes. However, once you drill down into discrete policy issues, different social justice claims do not always point towards similar policy outcomes. Sometimes they conflict with each other.

C. The Problem of Justice Conflicts

Sometimes, policy issues arise where different social justice claims will not run together. By “not run together,” I mean that analyzing the policy issue in question according to one or another type of social justice claim will suggest different policy outcomes that cannot be reconciled. As a result, the chosen policy will change depending on which social justice claim is prioritized. I call this a justice conflict. To speak in the abstract, a justice conflict is as follows:

Assume that Outcomes X and Y are opposing outcomes that cannot be reconciled.

1) Policy Issue P involves Social Justice Claims A and B.

2) If Claim A is applied to P, then Outcome X should be adopted.

3) If Claim B is applied to P, then Outcome Y should be adopted.

4) Given that Outcomes X and Y are opposing outcomes, Policy Issue P cannot be solved by appealing to Social Justice Claims A and B because each one advocates for the adoption of a different Outcome (X and Y, respectively).

One prominent historical example of a justice conflict took place during the labor unionization push in the early twentieth century and resulting union mergers in the mid-twentieth century. Early twentieth century labor unions had different strategic ways to increase membership.[95] On one hand, unions could expand membership to women and minority groups, which would further racial and gender justice goals. However, this strategy ran the risk of reducing the number of White men who would join because racist and misogynist White men might in turn reject unions as an organizing strategy or create competing exclusionary unions. This outcome would hinder the economic justice goals of the union, given that White men were the numerically dominant group in the labor force at the time.

On the other hand, unions could let local union chapters decide for themselves whether to exclude women and minorities, allowing the national union to silently acquiesce to racial and gender discrimination among its chapters. This position would consolidate their White male membership to improve their economic justice goals at the cost of harming gender and racial justice goals. Thus, labor unions were left with a choice—expand membership to improve racial and gender justice or restrict membership to maximize economic justice. In the early twentieth century, unions differed on which social justice claims to prioritize. However, in the 1950s, the biggest union in America, the newly merged AFL-CIO, chose the latter strategy to prioritize economic justice over racial and gender justice and subsequently dominated the union landscape in the ensuing decades.[96]

Presently, environmental and energy law are rife with justice conflicts given the massive socioeconomic restructuring that is needed to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. In addition to various Native American Tribes continuing to seek EPA permits for energy production,[97] the transition to renewable resources is creating justice conflicts not previously contemplated. One contentious justice conflict in climate policy is determining the net metering rate, or the monetary rate at which customers who produce excess energy from their solar panels sell that excess energy back to the utilities company. Initially, many states set the net metering rate at the full retail rate as an incentive for individuals to add solar panels. This meant that customers sold their excess energy to the utilities company at the same rate at which they bought the energy. Setting the net metering rate at the retail rate proved to be a significant incentive for solar adoption.[98]

However, given that solar panels continue to be expensive to purchase and install, solar panel installation has been heavily skewed among wealthy, White, and home-owning individuals.[99] While this distributional skew is concerning by itself, the downstream economic effect of this problem is often that utilities companies are making less money from these individuals and therefore need to increase prices on customers who are unable to install solar panels.[100] Prominently, the California Utilities Commission found that pegging its net metering rate to the retail rate “negatively impacts non-participating ratepayers” and “disproportionately harms low-income ratepayers.”[101] In effect, lower-income, minority, and renting individuals were subsidizing the reduced utility payments of those wealthier, Whiter, and home-owning individuals who installed solar panels.[102] Recently, multiple state public utilities commissions, including Hawaii,[103] Nevada,[104] Arizona,[105] and California,[106] have lowered their net metering rate below the retail rate. The net metering issue creates a justice conflict between maximizing environmental and climate justice and balancing these with economic and racial justice.

Another justice conflicts site in environmental and energy law occurs when policymakers determine how the benefits and burdens of our collective transition away from fossil fuels should be distributed. Labelled “Just Transitions” law,[107] one difficult issue is whether certain groups should get priority for new renewable energy jobs and training programs.[108] Some advocate that those workers who have become unemployed as a result of the transition should be prioritized, such as coal mining and production workers.[109] New Mexico and Colorado have followed this path.[110] Other states, such as Hawaii and New York, have instead prioritized improving the lives of those groups who have been most harmed by our carbon economy, such as low-income communities who live near energy production facilities and groups that may not receive a fair share of the economic benefits from a green economy.[111] This question of prioritization generates a complex justice conflict involving racial, energy, environmental, gender, and labor justice claims, among others.

Many commentators who advocate for social justice claims discuss policymaking at a very high level of granularity. For example, some climate justice scholars seek to determine the holistic legal, political, and technical solutions at the state, national, or international level that are needed to transition our economy away from fossil fuels.[112] This high level of structural thinking is important if we are to transition an entire integrated socioeconomic system that has existed for over a century. It is also a type of analysis that academics are in a unique position to address given our vocation and expertise.

However, such a high level of abstraction obscures the sharp edges down below.[113] It is easy to abstract away from conflicts within a policy issue if, on the whole, different social justice claims tend to run together over the entire policy domain (in this case, climate policy). But when policymaking is analyzed at the more granular level of individual policy choices, justice conflicts become unavoidable.[114] In this situation, when abstract social justice concerns are crystallized into a specific policy outcome, the policymaker is put in an unenviable position of choosing between social justice claims. While public law scholars have extensively discussed the fact that policymakers must make tradeoffs between different normative values, such as efficiency and fairness,[115] the literature has thus far paid less attention to the fact that tradeoffs also exist within normative values. In this case, justice conflicts present difficult tradeoffs within the concept of social justice.

Finally, it is important to note that commentators who adopt the internal and external accounts are right that social justice claims will often point toward the same outcome. While this Article advocates that scholars and practitioners should be mindful of the potential for justice conflicts and analyze them when they are present, not all policy areas that involve social justice necessarily involve a justice conflict. Consider the Dakota Access Pipeline project, which sought to build a 1,100 mile underground pipeline to transport oil from North Dakota to Illinois.[116] The pipeline passed under the Missouri River, the only water supply for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, which led to sustained protests and lawsuits by the Tribe and its allies.[117] As of October 2024, the easement had not been granted for this section of the pipeline.[118] In the case of Standing Rock, the different social justice claims—economic, racial, environmental, and climate justice—point to the same outcome of denying the easement for this stretch of the pipeline.[119] On many policy issues that concern matters of social justice, there will be no justice conflict.

D. Genuine vs. Illusory Justice Conflicts

Because of the widespread nature of justice conflicts, it is important to delineate a genuine justice conflict from an “illusory justice conflict,” or a conflict that appears like a justice conflict but can actually be resolved without appealing to higher-level principles, i.e., mid-level or basic justice principles.[120] Properly recognizing genuine and illusory justice conflicts is important for two reasons. The first reason is to mitigate false negatives. Given that much of public policy concerns allocating goods, resources, and privileges between different groups in society, policymaking conflicts could in fact be genuine justice conflicts even if policy actors do not use the language of social justice. This situation is likely to occur when policy actors avoid using the language of “social justice” for political or ideological reasons.[121]

The second reason is to mitigate false positives. Recognizing illusory justice conflicts is important because opponents of social justice often create illusory justice conflicts opportunistically as a political strategy to block social change. One prominent example of this tactic is its use by the police, who strategically make racial justice appeals grounded in the right of minority populations to live in a safe community as a means to reduce support for criminal justice reform. Dream Defenders, an abolitionist non-profit organization in Florida, ran into this potential justice conflict when it began its criminal justice reform advocacy efforts in Florida.[122] Their polling found that minority groups were receptive to the police’s framing, potentially complicating their understanding of the relationship between criminal and racial justice.[123] However, Dream Defenders subsequently found that being able to concretize alternative conceptions of what minority community safety could look like without more police led to increased support for reducing police funding among minority groups.[124] Dream Defenders found alternative means to satisfy the twin claims of criminal and racial justice by embracing the problems raised by their community, but rejecting the police’s framing of the solution.

Another recent example, which legal scholar Melissa Murray has extensively discussed, is Justice Thomas raising racial eugenics concerns regarding abortion to strategically pit reproductive and racial justice advocates against one another.[125] In her article, Murray argues that Justice Thomas failed to consider a number of considerations relevant to a comprehensive social justice analysis when he attempted to pit racial and reproductive justice in conflict concerning abortion. On Murray’s account, Justice Thomas did not include the voices of Black women regarding access to reproductive services and the structural barriers faced by women of color on reproductive decision-making matters.[126] These two considerations—centering the voices of Black women and considering structural barriers—are factors that should be included when examining applied justice claims of reproductive and racial justice regarding abortion. As Murray shows, once these additional factors are considered in the analysis, the appearance of conflict between racial and reproductive justice concerning abortion is significantly mitigated.[127] In these situations, actors framing the policy issue as a conflict for strategic reasons merely presents the illusion of a justice conflict.[128]

II. The Different Levels of Justice, in Theory and Law

Famously called “the first virtue of social institutions” by philosopher John Rawls,[129] justice is considered one of the most important principles in normative value theory.[130] Given the extensive literature on the subject and taking commentators at face value that their claims are about justice, this Article does not rehash debates regarding the content of justice. Let us simply consider the concept of social justice as giving persons and groups of persons in society what they are due or owed and the sociopolitical arrangements necessary to achieve such ends.[131] Thus, social justice is closely related to other normative concepts, including fairness and equality.[132] This definition is broad so it can include various forms of social justice, including distributive, procedural, and corrective justice.

This Part delineates a conceptual point regarding the concept of justice that is occasionally assumed in public law,[133] but has yet to be examined.[134] The concept of social justice operates at three different levels of abstraction: basic, mid-level, and applied. Once these different levels of social justice are explained, it will be shown that public law has largely focused on substantiating only the procedural justice elements of mid-level justice principles. While cost benefit analysis (CBA) is the prominent exception here, it suffers from well-known analytical problems when policy issues involve normative values that cannot be fully quantified. As a result, political institutions are currently without substantive guidance on how to make decisions on policy issues that create justice conflicts, which often leads them to publicly downplay the importance of such nonquantifiable normative values in their decision-making. The Part ends by advocating that institutions should adopt substantive mid-level justice principles as standing default rules in policymaking.

A. The Levels of Justice—Basic, Mid-Level, and Applied

There are many different kinds of social justice. The literature is replete with arguments regarding racial justice, procedural justice, gender justice, transformative justice, and a myriad of other types of justice. Some taxonomical housework is needed to organize these different parts of social justice so we can address what to do when justice conflicts arise. For our purposes, the level of abstraction of each type of social justice claim provides a helpful analytical vantage point. This focus will allow us to organize different social justice claims according to their place in the overall concept of social justice, in turn bringing us closer to a framework to analyze and potentially resolve justice conflicts.

There are at least three different levels of abstraction among social justice principles—basic, mid-level, and applied.[135] These levels vary along three dimensions: (1) their level of abstraction, which is synonymous with their level of generality, (2) their domain, meaning the scope of policy areas that they cover, and (3) the normative weight, or the strength of the reason they provide to act, that they provide to analyze a specific policy issue.

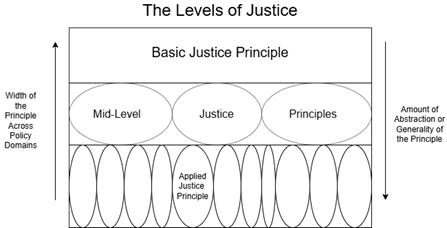

Diagram 1: Visual representation of the different levels of justice.

Assume for the purposes of this diagram that each vertical ellipse of an applied justice principle represents a single policy domain. A “basic justice” principle is the most abstract or general level of social justice claim. It purports to analyze what is owed to individuals or groups over the totality of social relations. Therefore, a basic justice principle seeks to have a domain that is synonymous with the domain of social justice itself. In short, it covers the entirety of social justice.

Rawls’s two principles of justice (the equal basic liberties principle and the fair equality of opportunity and difference principle) are the prototypical principles of basic justice.[136] According to Rawls, these principles should guide the creation of a new political state, including its constitution, economic system, and public institutions. However, the structural nature of Rawls’s basic justice principles mean that the principles are unable to provide any normative weight to analyze and determine the outcome for a specific policy issue, as will be explained more below.[137] Alternative basic justice principles include welfarism[138] and egalitarianism,[139] among others.

On the opposite end of abstraction is an “applied justice” principle. An applied justice principle operates at the least abstract, or most concrete, level because it determines the outcome for only one policy area as a matter of justice. Examples of applied justice principles include (1) in the case of a shortage, ventilators should first be given to younger patients,[140] (2) individuals charged with a crime should have a lawyer at all stages of the criminal trial process,[141] and (3) environmental law should be organized around a precautionary principle to mitigate the likelihood of significant harms.[142]

The exact level of specificity among different applied justice principles can vary. The problem of ventilator shortages during a public health crisis is more specific than the theory that should organize environmental law. However, notice that each applied justice principle operates within a single substantive policy area—public health, criminal law, and environmental law, respectively. This property delineates the domain of an applied justice principle; its scope or coverage is limited to a single policy area. To call for the precautionary principle to organize environmental law says nothing about whether the principle should organize a different area of law, such as criminal law. Therefore, an applied justice theory has a specific and demarcated domain restriction—the scope the theory pertains to—of one substantive policy area and cannot extend into other areas without additional theoretical scaffolding.

Regarding its normative weight, an applied justice principle is meant to provide a reason that is decisive as a matter of justice with respect to policy issues within its singular domain. Alternatively phrased, an applied justice principle, unlike a basic justice principle, gives you an outcome that you should adopt as a matter of social justice.[143] In Cass Sunstein’s influential phrasing, applied justice principles constitute the “low-level principles” that generate “incompletely theorized agreements.”[144]

To further elaborate the distinction between these levels of justice, it is useful to discuss how these levels can be misused when analyzing policy issues. One potential misuse of Rawls’s principles of justice is to ask how these principles would answer specific public policy issues. For example, one might ask, “How much should the top 1 percent be taxed under Rawls’s principles of justice?” Asking this question of Rawls’s principles would be a category mistake. The principles operate on a basic justice level, not an applied justice level. In short, there is a mischaracterization of the principles’ level of abstraction and their resulting ability to address the policy issue. The abstraction level of the tax policy issue (applied justice) does not match the abstraction level of the principle (basic justice). Thus, the basic justice principle does not provide any normative weight to answer the specific policy question at issue. An applied justice principle is needed if one seeks a principle that provides an outcome to determine the tax rate for the top 1 percent as a matter of justice.

The basic and applied justice literatures are extensive. However, there is a third level of justice principles that has received much less attention in public law or philosophy. I call this level mid-level justice principles.[145] As the name implies, mid-level justice principles are more concrete than a basic justice principle, but more abstract than an applied justice principle. Similarly, mid-level justice principles have a domain restriction that is wider than one policy area (applied justice principles), but less than the totality of social justice (basic justice principles). Mid-level justice principles provide pro tanto normative commitments that must be weighed or balanced against other values and the particular facts of specific issues before a decision can be reached.[146] Principles already discussed in public law that are actually mid-level justice principles include principles of procedural justice,[147] restorative justice,[148] the capabilities approach,[149] anti-domination,[150] and CBA,[151] among others.

Given their amorphous intermediate character, it is helpful to contrast mid-level justice principles from basic and applied justice principles. Mid-level justice principles are distinguished from applied justice principles by two features. First, a mid-level justice principle’s domain is wider than one single policy issue, and second, its normative weight is merely pro tanto, which is of a lesser weight than being decisive, as is the case for an applied justice principle. Regarding their domain, a mid-level justice principle can cover multiple policy areas, such as environmental, energy, and climate justice. The covered policy areas do not need to be related. In this respect, mid-level justice principles are trans-substantive, while applied justice principles are not. Consider cost-benefit analysis (CBA), which, as discussed in the next Part, is a mid-level justice principle.[152] CBA is trans-substantive because it can be used to analyze policy issues across different domains, such as environmental, securities regulation, and criminal justice policies.

However, in contrast to basic justice principles, mid-level justice principles do not purport to cover the totality of social justice. Therefore, different basic justice principles can potentially endorse the same mid-level justice principle.[153] It may be possible for both a Rawlsian and a welfarist to agree on a mid-level justice principle. As will be discussed later, it is also theoretically possible for multiple mid-level justice principles to overlap in a specific policy domain.[154] Consequently, while mid-level justice principles are trans-substantive, they do not cover the totality of all domains in which social justice operates, unlike a basic justice principle.

The second difference between mid-level justice principles and the other two levels of justice is the strength of the reasons it provides for resolving specific policy issues. In contrast to applied justice principles, which provide decisive reasons as a matter of justice for a specific outcome, mid-level justice principles provide merely pro tanto reasons, which point in favor of an outcome absent further justification. For example, the CBA result of a specific policy issue should then be evaluated in light of relevant variables that could not be included within the analysis, such as those values that cannot be quantified. Thus CBA, on its own, does not provide a decisive reason to adopt a certain policy outcome but instead provides a reason in favor of or against certain outcomes.[155] Instead, the CBA result should be analyzed with the other normative principles or values that could not be included in CBA to reach a final policy outcome. However, in contrast to basic justice principles, which are not useful when evaluating specific policy issues because of their breadth, mid-level justice principles can evaluate specific issues and provide reasons to adopt specific outcomes.

After the publication of A Theory of Justice by John Rawls in 1971, public law became fascinated with trying to build out Rawls’s principles of justice for constitutional matters.[156] By the end of the decade, the primacy of Rawls’s theory was so complete that legal theorist Mark Tushnet declared it was “the only game in town.”[157] Rawls’s dominance as a basic justice theorist in public law continued through the civic republicanism trend in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which attempted to fuse aspects of Rawls’s theory with the neo-republican revival taking place in intellectual history.[158]

However, the multiculturalism and pluralism debates of the 1980s and 1990s took their toll. Scholars began to push beyond liberalism’s basic proposition that the state should minimally interfere in conceptions of the good life and instead doubted the ability of our legal culture to agree on principles of basic justice.[159] This shift was most emblematic in Sunstein’s work. In the late 1980s, Sunstein argued for the Rawlsian-influenced civic republican revival.[160] However, by 1995 he began arguing that judges should make decisions based on “incompletely theorized agreements” given that judges likely disagree on matters of basic justice and other abstract normative theories.[161]

Even Rawls himself turned his back on his initial formulation of his theory after extended criticism questioned the ability of people who hold conflicting religious and ethical views to come to consensus on basic justice.[162] He then republished his new account in 2001[163] after publishing a series of articles during the mid-1980s to mid-1990s where he significantly modified his views.[164] As legal theorist Scott Shapiro noted in his 1997 review of Sunstein’s book on incompletely theorized agreements,[165] a “fear of theory” had begun to pervade public law and legal theory.[166] By the twenty-first century, building out principles of basic justice in public law appeared to be a lost cause. Public law has instead mostly embraced only procedural mid-level justice principles.

B. Public Law Has Primarily Adopted Only Mid-Level Procedural Justice Principles

Mid-level justice principles are not wholly foreign to public law. While these debates regarding basic justice were going on, policymakers worked to implement principles of social justice. In the second half of the twentieth century, Congress and the Executive passed a host of different measures that arguably improved social justice in policymaking. However, most of these measures only instituted procedural mid-level justice principles that require agencies to conduct certain additional procedures during policymaking. The notable exception is CBA, which is both a procedural and substantive mid-level justice principle. However, CBA suffers from well-known problems when attempting to include normative values that resist quantification. As a result, agencies and other political institutions currently have no consistent or principled mechanism to resolve justice conflicts that cannot be fully quantified when they arise in policymaking.

On the congressional side, statutes passed that included mid-level justice principles include NEPA, which requires agencies to conduct environmental impact analyses;[167] RFA, which requires agencies to conduct small entities impact analyses;[168] the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act (UMRA),[169] which requires consultation with state, local, or Tribal governments (SLTs) if a rule may result in SLTs spending over $100 million; the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA),[170] which requires agencies to make their records available to persons if requested; the Paperwork Reduction Act,[171] which requires agencies to submit Information Collection Requests to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) under certain conditions; and multiple amendments and alterations to the APA.[172]

These statutes, if they overlap with matters of justice, are primarily mid-level procedural justice principles.[173] Most requirements in these statutes require agencies to conduct specific types of analyses, consider potential alternatives to proposed actions, or consult with certain segments of the population before making decisions. In essence, these requirements mandate that agencies engage in specific procedures. However, they do not actually provide any reasons for or against adopting certain substantive outcomes. An agency could propose a rule, submit it through all of these procedural requirements, and still come out the other end with the exact same proposed rule without any substantive alterations.

Congress is not the only institution that has promulgated rules regarding the form and structure of policymaking. The President has also issued several trans-substantive executive orders (EO) that dictate how policymaking should be conducted.[174] However, most of these EOs have the same procedural focus. For example, EO 13,132 singles out a substantive value of importance—federalism—and imposes additional procedures for agencies to follow, such as providing a federalism impact statement and consulting with state and local officials about the proposed rule.[175] The connection between procedure and substance, if there is one, is nebulous.[176] Therefore, it appears public law has adopted procedural mid-level justice principles, but it has been silent on adopting any substantive mid-level justice principles.

CBA is the major exception. First required by President Reagan[177] and continued by each subsequent President,[178] CBA has become fully entrenched in executive policymaking.[179] CBA is both a procedural and substantive mid-level justice principle.[180] It is procedural because it requires agencies to engage in specific procedures, such as quantifying, monetizing, and adding up the benefits and costs of the proposed action. It is substantive because CBA asks agencies to adopt a specific decisional principle: Do not go forward with the proposed action unless the benefits outweigh the costs.[181] As such, CBA substantiates a welfarist mid-level principle of justice.[182]

Limitations and criticisms of CBA are extensive, so only a few brief points are needed. CBA forces policymakers to quantify, if not monetize, purported costs and benefits of a policy, including normative values such as fairness and justice, which are notoriously difficult to quantify.[183] In addition, these normative values are important, in part, because they are multi-scalar, meaning that the normative values are substantiated by multiple underlying justifications. CBA forces the various reasons supporting these values to be flattened through its cost-benefit decision-making structure.[184] The difficulty of quantifying normative values, combined with the flattening of these values, creates the possibility that CBA is structurally biased in favor of regulatory costs. These costs are often borne by industries that are incentivized to perform detailed cost analyses to prevent proposed regulatory policies from being implemented.[185]

Additionally, an incommensurability problem occurs when trying to compare different types of values during CBA.[186] Further, CBA masks distributional shifts between groups since it only aggregates costs and benefits.[187] Even some analytical choices within CBA itself, such as setting the discount rate, involve controversial normative choices.[188] Finally, the practice of quantification arguably degrades some values by asking how much individuals are willing to pay to be treated fairly or with respect.[189] In fact, simply framing the attainment of a basic normative principle in monetary terms may strike some as absurd or repulsive.[190]

As a result of these shortcomings, agencies neither have guidance on how to analyze nonquantifiable normative values, nor how to fold such values into CBA.[191] For example, the EPA’s Technical Guidance for Assessing Environmental Justice in Regulatory Actions, a one hundred twenty page document that delineates how EPA officials should analyze environmental justice concerns in regulatory actions, declined to provide any guidance on how EPA officials should analyze non-health related impacts of EPA actions because such impacts were too difficult to quantify.[192] Therefore, both EPA civil servants and potentially affected communities are left in the dark about how nonquantifiable dimensions of environmental justice are involved in EPA policymaking, if at all. Considering these problems, CBA appears methodologically difficult and normatively problematic as a standalone mid-level justice principle when important normative values are involved. Additional substantive mid-level justice principles are needed.

C. The Biden Administration’s Embrace of Analyzing Normative Values

Throughout its term, the Biden Administration began to update regulatory analysis to account for CBA’s shortfalls in situations when agencies should consider important normative values during policymaking. This focus was most evident in two Biden White House initiatives: (1) the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) finalizing new Circulars A-4 and A-94, which detailed how agencies should analyze regulations under EO 12,866,[193] and (2) the Justice40 Initiative,[194] requiring 40 percent of the benefits of certain federal environmental and infrastructure programs to be directed towards disadvantaged communities. Given that Justice40 showed the benefits and problems with a President-led effort to institutionalize a substantive mid-level justice principle, it will be discussed in more detail in Part III.[195]

The Biden Circular A-4, among other changes,[196] provided additional details on how agencies should engage in qualitative reasoning[197] and incorporate the distributional effects of agency actions.[198] It is clear from the Biden Circular that OMB focused on existing critiques of CBA and examined how to better include normative considerations into regulatory analysis. These efforts from the Biden Administration were laudatory.

However, the Biden Circular A-4 was permissive by design. It demonstrated the various ways that agencies could involve qualitative and normative reasoning into regulatory analysis. For example, the A-4 stated that “it would not be appropriate to attempt to fully measure the value of human dignity, civil rights and liberties, equity, justice, or indigenous cultures,” thereby giving agencies permission to not quantify some normative values.[199] However, it provided no guidelines about how agencies should actually analyze human dignity, civil rights and liberties, or any other normative value that resists quantification.[200]

The procedure for deciding how to include nonquantifiable normative values in regulatory analysis was also written in general terms—the agency should “present any relevant information that would inform an understanding of those effects . . . along with a description of the unquantified effects, such as (in the context of assessing a regulation that affects the environment) ecological gains or ecosystem services, improvements in quality of life, viewshed improvement, and indigenous culture preservation.”[201] The Biden A-4 used similarly general and permissive language when discussing when and how agencies could engage in distributional analysis during agency policymaking.[202] The only substantive suggestion in the A-4 was that the agency could choose to use distributional weights based on the diminishing marginal utility of benefits according to certain segments of the population. However, the guidance was again in general terms.[203]

Therefore, while the Biden Administration said agencies could consider substantive justice principles, agencies were still largely left to fend for themselves when deciding whether, which, and how normative values should be incorporated into policymaking.[204] As will be discussed more below,[205] the problem here is that agencies can strategically choose not to engage with normative concerns during their regulatory impact analyses.[206] Given this state of affairs, some agencies chose to either avoid the thorny normative and political issues relating to social justice or to consider such values in nontransparent ways during policymaking.[207]

D. Political Institutions Should Adopt Substantive Mid-Level Justice Principles

Given the long-standing deficiencies with CBA and prior presidential administrations’ lack of concrete guidance of how to incorporate normative values into regulatory analysis, there is currently an absence of substantive normative principles to guide political institutions. Yet, as the previous Part documented,[208] conflicts within normative values, such as social justice, are widespread in policymaking and will only proliferate as contemporary policymaking continues to get more complex. Importantly, as previously discussed,[209] justice conflicts will continue to occur in policymaking whether or not political institutions or government actors explicitly recognize them or speak of them in the rhetoric of social justice. This Article proposes one attractive method for political institutions, including future presidential administrations, to adopt substantive guidelines for analyzing normative values—political institutions should adopt mid-level justice principles as standing default rules.[210]

Political institutions can adopt specific mid-level justice principles to serve as standing methods of qualitative reasoning to analyze social justice claims and resolve justice conflicts. By doing so, the political institution justified ex ante its adoption of the mid-level justice principle before the institution engages in policymaking regarding any specific policy issue. The institution is not creating ad hoc forms of qualitative reasoning to resolve a particular justice conflict, but rather calling upon an already justified second-order mode of decision to help resolve this particular justice conflict and similar ones in the future.

Mid-level justice principles should operate as pro tanto normative reasons, or standing default rules, for political institutions to resolve justice conflicts. In doing so, they would provide a defeasible reason to support a certain outcome to resolve justice conflicts.[211] For any particular policy issue, there may be weightier countervailing reasons for an alternative outcome. However, those countervailing reasons would only apply for that specific policy issue. The mid-level justice principle would remain the standing default. While this discussion is in general terms, the next Part discusses multiple concrete ways that Congress, the President, and agencies can adopt mid-level justice principles.[212]

One might ask why mid-level justice principles should be institutionalized as default rules instead of rules of decision. There are two reasons. The primary reason is ontological. A mid-level justice principle serves as a general standing reason across the trans-substantive domain it covers. Given their generalized nature, mid-level justice principles cannot solve justice conflicts within a particular policy issue without additional theorizing and fact-sensitive analysis. Instead, these principles must be balanced or weighed against other normative and factual considerations relevant to that particular policy issue.[213] The additional theoretical scaffolding needed to resolve a discrete policy issue could come from within the concept of justice, such as if an institution adopted multiple mid-level justice principles that potentially conflict in a specific policy issue[214] or normative considerations relevant given the particularities of the specific policy issue, or other normative values, practical considerations, or political concerns.[215] As such, when adopting mid-level justice principles, institutions can still consider other normative, practical, or political values that may be important in certain policy areas.[216]

Second, mid-level justice principles do not consider values that are beyond the domain of justice. It follows that using mid-level justice principles as default rules allows institutions added flexibility to consider how to resolve the specific policy issue in question. For example, agencies analyzing specific policy issues can choose how to fold their mid-level justice principles into existing CBA practices regarding proposed regulations that contain social justice considerations.[217] In short, the institution can do a more comprehensive “cost-benefit analysis” if additional normative reasons can enter its analysis.

The adoption of mid-level justice principles as default rules has multiple normative benefits compared to the status quo.[218] First, mid-level justice principles provide a standing, and thereby stable, method to help resolve justice conflicts. Relatedly, these default rules, which will likely be adopted by higher-level officials given their general applicability, will provide concrete guidance to the frontline officials who carry out agency policies.[219] Additionally, interested parties know ex ante the modes of reasoning the institution will use to resolve justice conflicts, improving the institution’s transparency and shaping the types of arguments that interested parties make to the institution. Further, as will be discussed more below, institutions will likely be more resistant to interest group capture and rogue political actors, as they will have to justify any deviations from their adopted mid-level justice principles.[220]

The alternative to this proposal is a lack of standardized guidance for political institutions about how they should consider social justice claims when there are justice conflicts, thereby letting each institution figure it out on its own each time a justice conflict arises in policymaking. In essence, the alternative is the status quo.

However, recent doctrinal changes will make it more difficult for political institutions to reconcile justice conflicts in an ad hoc manner. For example, in the context of congressional delegations, the Supreme Court has cracked down on Congress delegating policymaking to agencies on significant political or economic issues absent clear statutory language through the major questions doctrine (MQD).[221] Recently unmoored from previous doctrinal limits,[222] the MQD now appears to be a roving license for courts to strike down agency policymaking on issues that contain significant social justice claims if such agency action cannot be tied back to existing statutory language.

Despite the A-4 Circular implemented by the Biden Administration, agencies continue to be without substantive guidance about whether and how social justice considerations should be involved in policymaking. When agencies are without clear standards about how to apply normative values, many agencies choose to not publicly discuss such normative values and instead retreat into forms of reasoning that are known to be accepted by reviewing courts, including technocratic reasoning and CBA.[223] Agency reticence to publicly disclose their normative principles creates variability between agencies concerning whether they disclose their analysis of normative values,[224] which is likely driven by agencies having different cultures of litigation risk tolerance rather than any underlying statutory and normative reason for such variation.

Alternatively, some scholars argue that agencies only consider normative values strategically in situations where they seek to promulgate a rule regardless of the quantified CBA estimates.[225] While agencies must often engage in normative reasoning given the moral considerations involved in many regulations,[226] agencies risk losing their legitimacy if they are not consistently and publicly reasoning how they weigh normative values.[227] Neither of these alternatives is appealing. This proposal provides an action-guiding method for agencies to conduct normative reasoning concerning social justice claims that is transparent to interested parties and legally justifiable to courts.[228]

One may question why this Article lacks a detailed list of preferred substantive mid-level justice principles. This Article does not provide such a list for multiple reasons. First, as will be discussed more below, specific mid-level justice principles will likely vary between institutions.[229] Therefore, a full cataloguing of preferred substantive mid-level justice principles will likely be both unhelpful and counterproductive given this institutional variation.

Second, political institutions should themselves generate their preferred mid-level justice principles in deliberation with those they represent and other affected persons. As I’ve previously argued in the context of the administrative state, a theory of democracy grounded in a thick conception of political equality requires policymaking to be structured in a manner that prioritizes the inclusion of persons who will potentially be affected by the policy in question.[230] Political theorist Danielle Allen has recently extended such a position by arguing that democratic governance is required for a political community to attain justice because democratic practices are the only ones by which the citizenry are meaningfully involved in determining the parameters of their own flourishing.[231] Crenshaw’s concept of political intersectionality is also important here, as political institutions should have processes for inclusion that are sensitive to the different overlapping forms of subordination faced by different groups within the general category of affected persons.[232]

In short, democratic policymaking itself should guide the adoption of preferred mid-level justice principles, rather than abstract, ex ante theorizing unconnected to affected persons. Therefore, the normative desirability of implementing specific mid-level justice principles is likely to vary according to multiple variables, including the institution and affected political communities in question. Instead, the primary purpose of this Article is to make the conceptual point regarding the existence of mid-level justice principles within the concept of justice, advocate that political institutions should adopt them to analyze justice conflicts, and demonstrate how institutions can structure them into policymaking.

This being said, one mid-level justice principle likely to be normatively desirable across political institutions is an egalitarian reparative justice principle.[233] This principle would entail that institutions have a defeasible obligation to resolve justice conflicts in favor of the claim that gives what is owed to groups who have been previously unjustly harmed by the federal government until such groups stand in qualitatively equal relations to groups who have not been harmed.[234] That is to say, when such groups will be affected by a policy issue, political institutions should prioritize the claims of those who have been previously harmed by the American government to help equalize relations between citizens.[235] An egalitarian reparative justice principle should be adopted because democratic governance is ultimately grounded in a principle of political equality between persons tied to a conception of joint authorship.[236] Political equality cannot be achieved in theory or practice so long as groups in this country continue to be scarred by the political, social, and economic effects of past state-sanctioned harms because such harms continue to alter their ability to meaningfully participate in democratic policymaking.[237]

Groups likely to be prioritized in policymaking according to this reparative justice principle include Native persons,[238] some minority ethnic and racial communities,[239] and LGBTQ+ communities,[240] among others. For example, Colorado recently harmonized the term “disproportionately impacted communities” across various statutes to include historically marginalized communities,[241] defined as communities who have suffered prior and continuing state-directed harms.[242] This statutory language serves as a template of how communities can be identified under a reparative justice principle, and how such a principle can be implemented across different statutory and regulatory regimes.

Given current equal protection caselaw,[243] institutions adopting explicitly race conscious policies face an uphill hurdle.[244] However, an egalitarian reparative justice principle could likely withstand constitutional challenge on equal protection grounds given that it is facially race neutral and the prioritization can be linked to past state or state-sanctioned harms against the community in question.[245] In fact, federal agencies have used, and continue to use, economic or social disadvantage to preference applicants for government services and contracts for decades.[246]

In the case of the Navajo petition to build Desert Rock, this reparative justice principle would create weighty pro tanto reasons that the EPA should have granted the pollution permit despite the environmental harms that would result, so long as the Navajo Nation has determined building the plant is the best path forward for their community.[247] The strength of the Nation’s claim under this reparative justice principle is further strengthened because the U.S. government and multiple corporations made the Navajo lands into extractive spaces in the first place.[248]

One concern with adopting mid-level justice principles may be whether the proposal is radical enough. Many commentators invoke social justice claims to inspire radical changes to law and politics.[249] This criticism states that having political institutions consider mid-level justice principles may be normatively beneficial, but it hardly seems like the radical reformation that many social justice movements aspire to achieve in our society.

There are a few responses to this concern. First, institutions having a standing, public default rule that prioritizes certain mid-level substantive justice principles across the board is a quite radical departure from existing policymaking, which currently only include social justice considerations on an uneven, ad hoc, and nontransparent basis.

Second, while abstract calls for “radical imagination”[250] and “wholesale transformation”[251] are important to shift our conceptions of what is possible, these calls need to be concretized and institutionalized if they are to guide policymakers. This proposal is meant to begin a conversation about how social justice claims should be embedded within the state itself.[252] It’s not an either-or situation; both forms of action are needed and can work together synergistically.[253]

A related concern is that while justice conflicts do arise in discrete policy issues, focusing on the conflict masks the underlying structural features that gave rise to the policy choices that generated the justice conflict in the first place.[254] Such structural features of sociopolitical power should not be abstracted from view during policymaking. However, the strength of this concern depends on the particular institution it is directed toward and the actors involved in the policy issue in question. In short, structural critique should integrate agentic and institutional dynamics regarding specific policy issues.[255]

At the institutional level, the concern is strongest when lodged at Congress, which has the explicit constitutional power to fundamentally reshape our sociopolitical order to address underlying sources of structural hindrances.[256] However, many policymakers don’t have the power to substantiate radical transformations of our sociopolitical order absent new or explicit statutory authority.[257] Meanwhile, the ability of agencies to reinterpret old statutes for new regulatory purposes has recently been curtailed by the rise of the MQD, as will be discussed in the next Part.[258] Nevertheless, frontline policymakers need guidance now about what to do when they are faced with justice conflicts given their existing authority. Adopting mid-level justice principles provides one appealing method for how well-meaning policymakers concerned about social justice can institutionalize these concerns.

III. Institutionalizing Mid-Level Justice Principles