Inclusive Occupational Licensing

Occupational licensing has been under attack from across the political spectrum. Economists argue that it is inefficient and costly; policymakers argue that it limits employment opportunities and hurts consumers; and antitrust regulators argue that it limits competition and creates cartels. Politicians, regulators, and courts have come to a rare consensus that licensing regimes must be restricted or repealed. Despite the critiques, licensing has remained entrenched, while other anti-competitive labor market practices, such as non-compete clauses and employee misclassification, have been targeted by federal agencies and state legislatures. The result has been worsening inequality, exclusion of disadvantaged workers from lucrative career paths, and limited access to services by consumers.

This Article reimagines licensing in the twenty-first century as a source of opportunity rather than a pure barrier to entry. When an industry is already licensed, additional paths for entry that target underprivileged populations benefit workers and consumers. We suggest that this approach can strengthen workers’ labor market power and diversify a variety of industries, including those where workers are less educated, lower income, and more vulnerable.

In this Article, we argue that the solution to licensing’s well-established problems is not less licensing, but the opposite—new licenses should be introduced to diversify access within licensed professions. For example, we look to the medical industry, which successfully implemented an expansion in licensing that resulted in more medical care offered to vulnerable patients and more employment opportunities available to healthcare workers.

To demonstrate our proposal’s promise of fighting inequality, we focus on a new case study of licensing for home food businesses. We collect novel empirical data on home food licensees registered in California after the passage of the Homemade Food Act of 2012 and demonstrate how home food licenses are held by underrepresented minorities. Moreover, we show how home food businesses are often located in food deserts, filling gaps in California’s food ecosystem. Expansions in food licensing disproportionately benefit underprivileged workers and consumers.

We argue that licensing, when used strategically to benefit disadvantaged communities, can be a powerful weapon against inequality. We provide a framework for expanding licensing regimes to reap the benefits of competition and to diversify licensed industries. More accessible licenses can help low-income and minority license holders enter new professions at a lower cost, provide a path to higher income, and create a community with shared resources and information. In an increasingly unequal society, inclusive licensing can fight anti-competitive labor practices while contributing to the welfare of both workers and consumers.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

A recent high school graduate, a factory worker let go after a decade of loyal service, and a retiree returning to the work force to support their grandchildren each face a common challenge in the job market: They cannot apply for a job as a manicurist, garment worker, or security guard without receiving a state license.[1] Licenses impose training, examination, registration, and ongoing supervision requirements that workers must satisfy.[2] Unlicensed workers may face lawsuits and other sanctions if they are deemed to have entered the license holders’ territory.[3] Consumers suffer due to a lack of available services.[4]

From the early 1950s to 2008, the share of workers covered by licenses grew from less than 5 percent to 29 percent.[5] In nearly that same time frame, economic inequality grew exponentially. From 1947 to 2018, households in the highest income quantiles saw their real incomes grow by more than double that of the lowest income quantiles.[6] Protectionist licensing regimes that inflate wages only for license holders to the detriment of other workers may have contributed to the growth of inequality.[7] Accordingly, a chorus of scholars and policymakers has warned of the harms of licensing, advocating for the repeal of licensing regimes or aggressively attacking license holders’ power.[8] Proposals for reform have focused on repealing licenses in favor of less onerous regulations or relaxing existing licensing laws.[9]

These proposals have created a rare bipartisan consensus in favor of licensing reform. In 2015, the Obama administration composed a full-length report on the effects of occupational licensing alongside preparing several policy proposals and funding for the Department of Labor to study interventions in state licensing policies.[10] Similarly, the Trump administration issued an executive order in 2020 pointing to the urgent need to reform occupational licensing, requiring federal agencies and states to work together to implement licensing reforms when possible.[11] The Biden administration’s executive order convening a multi-agency coalition to combat anti-competitive labor practices specifically referred to licensing reform as a priority.[12] Nevertheless, federal rules targeting licensing reform have not emerged, and states have not taken significant steps to repeal licensing regimes.[13]

In the meantime, federal and state governments have taken other high-profile steps to limit anti-competitive labor market practices.[14] Proposed reforms to address employee misclassification, non-compete agreements, and mandatory arbitration have been successfully adopted.[15] Occupational licensing reform has seemingly been deemphasized in national politics,[16] while mandatory arbitration[17] and non-compete agreements[18] remain a policy priority. In fact, licensing reforms have faced significant pushback from industry insiders, stalling attempts for widespread change.[19]

We propose a new path forward—expanding licensing regimes to diversify job options for workers entering a particular industry, which will also benefit consumers.[20] Simply put, multiple licenses competing for consumers decrease the power wielded by any single licensing authority and expand consumer choice. At the same time, more options allow a larger number and a more diverse group of workers to enter a profession. This approach reimagines licensing considering current economic conditions, where many industries require licenses already. Diversifying licenses for workers to increase access to professions makes expansions in licensing an important force against inequality and in favor of economic opportunity.

To begin, we analyze the potential costs and benefits that licenses create for disadvantaged populations.[21] First, we acknowledge the discriminatory history of licensing regimes.[22] The power for insider licensing authorities to exclude outsiders has been used to oppress less powerful workers, including disadvantaged minorities who may be averse to legal proceedings.[23] We then turn to the documented economic consequences of licensing on low-income and minority workers.

First, licensing creates a barrier for competitors who wish to enter the market to create a good or service.[24] Fewer entrants mean less competition for license holders.[25] The consumers in these markets may suffer because they have fewer options and higher prices, raising antitrust concerns.[26] The benefit of less competition, though, is protection for license holders from the vagaries of the market, allowing more long-term investment, and providing insurance against downturns, which is particularly valuable to low-income and minority workers.[27] Furthermore, a large body of literature has shown that licensing increases wages, benefiting the neediest workers most.[28]

Second, licensing assures consumers that all members of an occupation satisfy legal requirements that are intended to ensure minimum quality standards are met.[29] These prerequisites exclude workers without formal qualifications, potentially harming vulnerable worker populations such as immigrants and non-English speakers.[30] It may also decrease the availability of goods and services for consumers.[31] The benefit of requiring formal qualifications for licensing, however, is that market participants likely to commit fraud or provide low-quality goods or services are less likely to enter the market or remain in business.[32] Vulnerable consumers can feel more confident buying a good or service from license holders.[33] Moreover, licensing can help combat discrimination in the hiring market by providing an independently verified signal of a worker’s skill.[34] Biased employers can learn from the signal and begin to hire more diverse workers.

To demonstrate how expanding licensing regimes can benefit workers and consumers, we develop two examples. To begin, we describe the widely known success story of advanced practice nurses who work with, and have begun to compete with, medical doctors.[35] Restrictions in the supply of medical doctors have limited access to healthcare nationwide, especially in low-income and rural areas, but advanced practice nursing has helped fill the gap.[36] The shift has also lowered barriers for entry into the practice of medicine by decreasing the cost of education and increasing diversity in the composition of healthcare providers.[37] Both potential healthcare workers and patients have benefited, decreasing the power of medical doctors.

Next, we introduce a novel case study of newly created licenses for home food businesses. Food industry regulation has been criticized for its piecemeal approach to ensuring production and access to essential goods, especially for poor consumers.[38] The commercial food industry has resulted in “food deserts[,]” often poor or rural areas where access to healthy food is limited.[39] Despite these gaps in access, home cooks were historically limited from preparing and selling food commercially.[40] A movement criticizing this restriction, known in some states as the Food Freedom movement, gave rise to a sea change in state law over the past twenty years.[41] By the writing of this article, every state had allowed the sale of some foods produced in home kitchens.[42]

In 2012, California passed the Homemade Food Act, which allowed the production and sale of low-risk prepared foods, such as baked goods, at home if producers obtained a “cottage food” license.[43] Licenses were granted by county public health departments alongside traditional food facility and mobile food (food truck) licenses.[44] In 2019, California further expanded home food licensing to include Microenterprise Home Kitchen Operations (MEHKO) permits, which allowed home cooks to produce and sell hot foods.[45] These expansions in licensing were accompanied by minimal but necessary training requirements, inspections by county public health departments, and restrictions on revenue and the size of the business.[46]

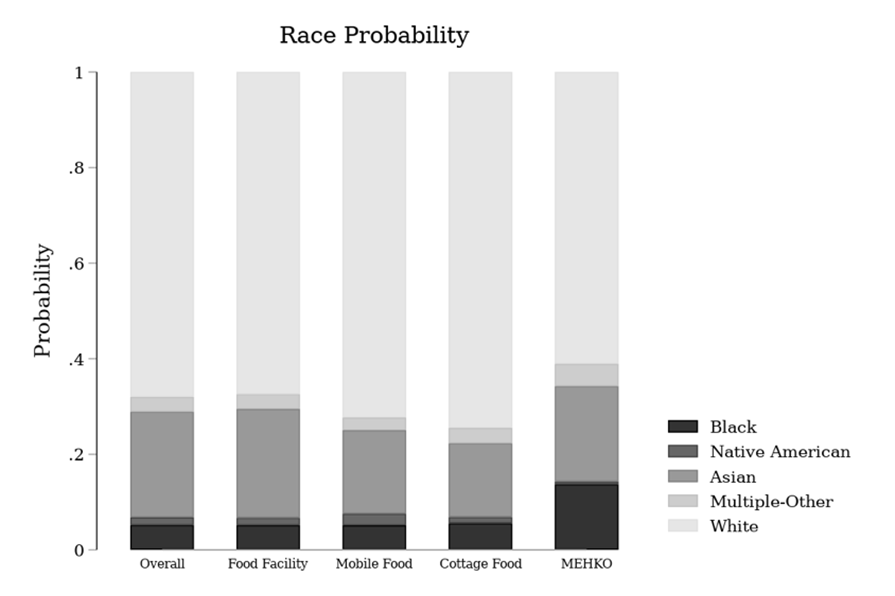

We introduce novel empirical evidence about how these new licenses limit the harms of licensing and create benefits for underrepresented populations. To begin, we gather the first comprehensive dataset of food business license holders in California through a series of open records requests. Since the passage of the Homemade Food Act in 2012, more than 6,500 cottage food providers have obtained a license in California, constituting more than 3 percent of licensed food facilities in the state.[47] Over two hundred MEHKO license holders have also been licensed, even though very few counties have approved the issuance of MEHKO permits.[48] Based on the names and locations of license holders, we estimate their race, ethnicity, gender, and income.[49] Comparing data across license types, we find that mobile food, cottage food, and MEHKO licenses diversify the identity of license holders and expand consumer access to prepared food.[50]

Mobile food license holders are disproportionately Hispanic and serve low-income areas.[51] Cottage food license holders are disproportionately female. MEHKO license holders are disproportionately Black.[52] These licenses tend to be located in food deserts, as designated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), where access to quality nutrition is low.[53] We interpret the findings as evidence that carefully targeted licensing expansions can fight inequality and create a more inclusive market for food.

Given the benefits licensing can have for disadvantaged workers, we suggest that creating competition in licenses would be beneficial in most industries.[54] Our approach suggests that expansions in licensing can be progressive if (1) a new license is created within an existing licensed occupation, (2) the cost of obtaining the license and beginning work is significantly lower than the existing license, and (3) the new license is restricted to deter capture by powerful interest groups. Moreover, licenses should provide pathways for license holders to grow and become more profitable over time.

The first quality is key because imposing licensing requirements on an unlicensed occupation grants a monopoly to the community of license holders, which exacerbates the negative aspects of licensing.[55] Introducing a new license to compete with existing licenses in the same occupation harnesses the power of competition to diversify the population of license holders.

The second quality of a successful expansion in licensing is a low cost of entry, considering both financial and non-financial barriers that a new license holder must overcome to begin work.[56] Training should be available even for those without formal schooling, and registration requirements must be spelled out clearly and in multiple languages.

The third quality is that the license must be restricted so that it does not appeal to more powerful or entrenched interests in the same market.[57] We propose that restrictions on the physical size or location of the business would help diversify the market without unduly limiting the success of new license holders.

Finally, we propose that any expansion in licensing must provide license holders pathways to growth, whether through access to “upgrades” to more prestigious licenses or through a defined path to profitability.[58] Licensing can therefore enable, rather than limit, social mobility.[59] This approach will help minimize the downsides of licensing while emphasizing the significant benefits licensing can create either for license holders or their communities.[60]

In summary, carefully designed expansions in licensing cannot negate all ill effects licensing has historically wrought, but they can help harness the worker and consumer protection benefits for the neediest populations. Part I explains the effects of licensing on inequality, both positive and negative. Part II describes the current state of licensing reform, starting with policymakers’ past attempts and ending with the unlikely success story of advanced practice nursing. Part III introduces our case study of food businesses, describes its importance, and provides statistical evidence from novel data in California. Part IV details the qualities of successful licensing reform and concludes.

I. Licensing and Inequality

By its very nature, occupational licensing creates inequality. License holders are privileged with the ability to enter an occupation, while other workers are limited and threatened with legal action if they engage in unlicensed practice of the same occupation. Moreover, there are costs to obtaining a license that prevent low-income, minority, and otherwise disadvantaged individuals from joining the privileged group. Licensing regimes usually require workers to pay licensing fees and undergo some type of costly training. There are additional costs from having to satisfy ongoing compliance requirements.[61] Despite critics regularly mentioning these costs,[62] occupation licensing has continued to grow, suggesting that some benefits of licensing do accrue to license holders and their customers. In particular, licensing tends to increase the quality of goods and services for consumers. Licensing also increases wages for license holders, benefiting underpaid workers.

What impact does licensing have on minorities and other disadvantaged populations? Empirical data has shown that occupational licensing has coincided with the growth of economic inequality over the past fifty years.[63] Moreover, legal scholars and sociologists have shown how licensing regulation has been historically misused to exclude racial minorities and other disadvantaged workers from lucrative careers. For example, David E. Bernstein explains the discriminatory practices enabled by licensing regimes, arguing that licensing was often intended to exclude disadvantaged minorities from lucrative occupations.[64] Bernstein gives several examples of facially neutral licensing laws that were enforced by discriminatory institutions that used their discretion to prevent minorities from becoming doctors, plumbers, and barbers.[65]

Modern empirical research has provided a more nuanced picture of how licensing impacts minorities. In this Part, we summarize recent research with a focus on two key roles played by licensing regimes and describe their impacts on vulnerable and disadvantaged populations. First, we consider the role of licensing as a barrier to entry. Second, we consider the role of licensing as a signal of quality.

A. Licensing as a Barrier to Entry

Licensing creates barriers to the entry of new workers by requiring potential entrants in a particular field to satisfy costly regulatory requirements, such as education, testing, and registration.[66] This feature of licensing has caused concern because potential entrants may find it too costly to overcome these barriers, causing labor shortages and limiting the availability of the services licensed workers are providing.[67] Moreover, consumer prices may increase. Conversely, license holders benefit from fewer competitors entering their market, as evidenced by higher wages in licensed occupations. The following section analyzes the differential impacts of these costs and benefits on inequality.

1. The Costs: Lower Labor Supply and Higher Prices

Barriers to entry decrease the supply of labor and raise prices in a market, causing significant harm to unlicensed workers and consumers. Some evidence shows that women, racial and ethnic minorities, and other disadvantaged populations bear the highest of these costs.

To quantify the overall number of jobs lost due to licensing, Peter Q. Blair and Bobby W. Chung use nationwide survey data. Their approach compares the share of workers in a specific occupation in a state where that occupation is licensed, relative to a bordering state where the occupation is unlicensed.[68] The assumption underlying their work is that people in licensed states are similar to those in unlicensed states, but for the regulatory regime they face. When those assumptions hold, Blair and Chung find that licensing causes a more than 20 percent drop in the supply of labor, measured discontinuously at the state border.[69] The drop persists even when comparing jobs across borders with similar wages and licensing requirements on either side.

The costly effects of licensing-induced barriers to entry are likely to disproportionately impact disadvantaged workers. In early work, Stuart Dorsey documents the harms licensing regimes impose on workers who do not overcome these barriers to entry.[70] Using data on written cosmetology exams in Missouri and Illinois, Dorsey shows that low-income, Black, and immigrant test takers had higher failure rates than less disadvantaged populations.[71] Drawing on a variety of contemporaneous work, Dorsey demonstrates that licensing regimes take advantage of differences in background qualification, levels of education, and income to systematically screen out disadvantaged applicants.[72]

Chung provides a modern empirical example, studying real estate agents.[73] The paper focuses on the introduction of Illinois’ 2011 amendment to the Real Estate License Act.[74] The amendment required licensed agents to complete thirty hours of training and pass an exam to renew their license.[75] To evaluate the effect of this rule, Chung gathers administrative data on real estate agents’ registrations over time across the country.[76] Chung then compares agents affected by a shift in licensing law in Illinois with a “synthetic control” group of agents with similar characteristics outside Illinois.[77] Comparing the Illinois agents to those in the control group, Chung finds that an increase in licensing requirements caused a drop in agents’ license renewal rates.[78] This drop in employment specifically impacted women, who exited in larger proportions.[79]

A lower supply of labor means that licensed individuals who do enter the market can command higher prices. As a result, consumers will have to pay more, if they can afford to purchase those goods or services at all. Chiara Farronato, Andrey Fradkin, Bradley Larsen, and Erik Brynjolfsson demonstrate these effects using data from an online platform that matches homeowners with home improvement service providers, such as painters, designers, and contractors.[80] They compare within occupation across states with and without licenses, and confirm the effect found by Blair and Chung—fewer workers are available in licensed occupations. Moreover, Farronato, Fradkin, Larsen, and Brynjolfsson have information about how much workers charge for their services when facing more or less stringent licensing criteria.[81] More stringent licensing regimes were associated with a 3.9 percent higher price to consumers.[82] Though there is no analysis in this paper of which consumers pay these higher prices, a large literature on “retail redlining” suggests that minority customers often pay more for food, loans, and other goods and services.[83]

Taken together, the scholarly research shows that there are severe discriminatory impacts of licensing on the selection of workers allowed to enter an occupation. Furthermore, there are likely additional negative impacts on vulnerable consumers who face higher prices in markets where workers must be licensed. The barriers to entry created by licensing, both historically and in modern institutions, have the potential to worsen existing social inequality.

2. The Benefits: Higher Wages for License Holders

The barriers to entry that licensing introduces are not entirely harmful, as their enduring popularity suggests. For workers who can overcome barriers to entry, licensing weakens competition and decreases risk.

Farronato, Fradkin, Larsen, and Brynjolfsson document that when consumer prices increase for home services, the natural consequence is an increase in wages for license holders.[84] Morris M. Kleiner and Alan B. Krueger use a large dataset to estimate that licensed occupations enjoy 18 percent higher wages than unlicensed occupations.[85] Edward J. Timmons and Robert J. Thornton document that wages of licensed radiologic technicians are nearly 7 percent higher compared to identical counterparts in states without a licensing requirement.[86] Kim A. Weeden expands this analysis to compare licensing with other laws, such as credentialing, certification, and unionization, in its effects on wages.[87] Weeden finds, in line with other scholars’ estimates, that licensing creates a 9 percent premium, while credentialing and certification seem to have even larger wage effects.[88]

Though disagreements exist about the size and significance of a licensing wage premium,[89] theory suggests that barriers to entry of all types cushion workers from market fluctuations.[90] Nick Robinson refers to these benefits as “buffering producers from the market” and explains that workers, in particular, need these benefits as other worker protections, such as labor unions, have declined in influence.[91] The added job security, along with the attendant freedom to invest in a long-term career, can make licensing a valuable tool for disadvantaged workers.[92]

Recent empirical work suggests that wage increases disproportionately benefit minority and female workers by closing wage gaps. Blair and Chung study the effect of licensing in professions on the employment of Black men.[93] Using a large dataset across multiple professions, they find that licensing decreases the Black-White wage gap.[94] They estimate that licensing increases White men’s wages by 3.6 percent but increases Black men’s wages by 16.3 percent on average, negating baseline disparities in wage.[95] Similarly, Xing Xia shows that licensing can decrease race-based wage gaps between female workers, using data on the market for dental assistants.[96] New X-ray licenses were introduced between 1970 and 2010 to increase dental assistants’ scope of practice.[97] Xia finds that in states with X-ray licenses, wages for non-Hispanic White dental assistants fell by 4 percent and the wage gap with minority dental assistants decreased by 8 percent.[98]

Licensing creates barriers to entry that could significantly benefit minority license holders. Higher wages, more job security, and lower wage disparities would overwhelmingly benefit vulnerable groups because they face more risk and have less security than more privileged populations.[99]

B. Licensing as Quality Signal

A key theoretical benefit of licensing is to certify that any worker practicing in a licensed occupation can provide a minimum quality of service.[100] Hayne E. Leland describes the problem as a variation on George A. Akerlof’s “Market for Lemons.”[101] A consumer buying a complex service, such as home repairs, will not know before their purchase whether or not the service provider will do a good job. Without a licensing regime, consumers will know that they will occasionally lose money on repair jobs, ultimately decreasing their willingness to pay for repairs. High-quality repair people will not be able to communicate their skill to consumers because all workers will claim that they can do the job.

A signal of quality that is costly and only worth obtaining for high-quality workers distinguishes high-quality from low-quality service providers and solves the quality-of-service problem.[102] Licensing is an important signal of quality, since it requires training, registration, and other tasks that only high-quality service providers are able to complete. Then, consumers will be willing to pay more to hire a licensed repair person, confident that they will be able to complete the job. Licensing can improve both workers’ and consumers’ well-being by creating more trust in markets that otherwise are fraught with misinformation.

For licensing to work as intended, however, consumers must be aware of the licensing regime and trust that it only licenses high-quality workers. However, licensing standards set internally by existing market entrants may be excessively high, resulting in unnecessary exclusion of high-quality workers. Below, we describe how these costs and benefits may differentially impact disadvantaged populations.

1. The Costs: Inattention and Unintended Consequences

Licensing regimes can fail to benefit consumers if they do not value the qualities licenses promote or if they have the unintended consequence of excluding workers or consumers from markets. Moreover, an inapt licensing regime that does not directly benefit consumers creates costs, which are more often borne by vulnerable groups.

Farronato, Fradkin, Larsen, and Brynjolfsson provide an example of consumer indifference to licensing.[103] Analyzing an online platform that matches homeowners with home improvement service providers, the authors estimate consumers’ willingness to pay a premium for licensed service providers.[104] They show that on average, consumers in the home improvement market have the same willingness to pay for licensed and unlicensed workers.[105] Despite this, consumers in markets that require licensing have less access to service providers since fewer providers exist in the market.[106]

Whether or not consumers value licensing, there is empirical evidence that even successful licensing interventions that increase quality of service have unintended negative consequences. For example, they decline service availability. Janet Currie and V. Joseph Hotz study daycare regulations to demonstrate an important example in the childcare context.[107] They study the effect of minimum education requirements using outcome survey data that includes deaths and serious injuries.[108] They show that an expansion in education requirements for daycare workers decreases accidents and increases the quality of daycare provided.[109]

But unintentionally, this regulation hurts a subset of children by limiting their access to licensed daycares and pushing them into more informal arrangements.[110] Even though average injury rates decline, the children excluded from daycare may have higher injury rates and receive lower quality care.[111] Currie and Hotz’s work also shows that the benefits of daycare quality increases accrue disproportionately to privileged populations, such as White children and children of college-educated mothers.[112]

2. The Benefits: Less Discrimination and Higher Quality

Despite the costs, signaling quality through license acquisition may have specific benefits for disadvantaged workers. Licensing conveys the quality of a worker to two audiences—the labor market and the consumer market. In both instances, empirical work shows that minorities receive particular value from licensing.

In labor markets, licensing provides an independent signal of workers’ competence. Informative signals can combat discriminatory hiring practices if employers are biased against hiring minority workers due to perceived gaps in competence.[113] Licensing benchmarks can help ameliorate employer bias by creating objective standards of competence that are more difficult for employers to ignore.

Several empirical papers provide support for this theory. Marc T. Law and Mindy S. Marks show, in an influential paper, that licensing benefited female and Black worker participation in some occupations.[114] Gathering data on workers in eleven occupations between 1870 and 1960, Law and Marks code the differential adoption of licensing regimes across states during that time period.[115] For each occupation, they estimate the effect of licensing on Black and female participation. Their results are mixed but not entirely negative. Licensing decreases the number of Black barbers, which is consistent with historical work that suggests barber licensing regimes were specifically intended to exclude Black workers.[116] On the other hand, licensing increases the number of Black nurses and the number of female engineers, pharmacists, plumbers, and nurses.[117] Law and Marks conclude that licensing does not necessarily harm minorities in an occupation.[118] Instead, the effect of licensing depends heavily on the circumstances, the occupation, and the licensing authority’s intent.[119]

Other papers provide support to this view. Blair and Chung show that licensing can combat racial discrimination in hiring.[120] Using a nationwide database of state licensing changes, they compare the effects of licensing in states with and without “Ban-the-Box” (BTB) rules, which limit employers’ access to employees’ criminal histories.[121] Previous literature had suggested that BTB rules increased employer discrimination against Black men because employers were replacing individual information about criminal records that they had before BTB with discriminatory beliefs.[122] But Blair and Chung show that licensing disproportionately benefits Black men in BTB states, which may fight labor discrimination.[123]

Other disadvantaged groups also benefit from licensing. Beth Redbird and Angel Alfonso Escamilla-García show that these benefits extend to skilled immigrants.[124] Their work compares the likelihood that adult-entry foreign-born workers are included in a particular occupation after they enter the United States.[125] They find that workers are more successful in obtaining positions in licensed occupations than in unlicensed occupations.[126] Redbird and Escamilla-García posit that licensing substitutes foreign-born workers’ lack of network in the U.S. labor market.[127] Taken together, the literature on licensing and its impact on disadvantaged groups suggests that licenses help female, Black, and foreign-born workers fight informal labor market exclusion by privileged groups.[128]

Beyond signaling to employers, licensing can directly improve the quality of services being provided by licensed workers. These benefits often accrue to minority populations, who are otherwise most vulnerable to low-quality or fraudulent transactions. Two high-profile examples from contemporary empirical literature illustrate this point. Bradley Larsen, Ziao Ju, Adam Kapor, and Chuan Yu show that more stringent licensing improves the lower end of the teacher quality distribution and increases the quality of teaching.[129] Using survey data, they demonstrate that teacher quality, proxied by the selectiveness of teachers’ universities, improves when licensing stringency increases in contexts where initial quality is lower.[130] They find no disparate effect on high-minority or high-poverty districts even within this sample.[131]

In the healthcare industry, D. Mark Anderson, Ryan Brown, Kerwin Kofi Charles, and Daniel I. Rees study the effect of licensing midwives on maternal and infant health.[132] Between 1900 and 1940, twenty-two states introduced licensing requirements for midwives, including educational requirements and more subjective assessments.[133] Anderson, Brown, Charles, and Rees gather data on state and municipal mortality rates of mothers and babies, and they compare states with no change in their licensing laws to those that introduced licensing requirements for midwives in that year.[134] The authors find that licensing midwives decreases maternal mortality by 7 percent and slightly decreases infant mortality.[135] These effects are most pronounced in areas with large Black populations, suggesting that Black mothers and babies benefited most.[136]

Taken together, these studies suggest that licensing as a signal of quality can benefit minority workers and their customers. Licensing appears to most benefit vulnerable communities who, as consumers, are the most likely to receive low-quality goods and services, or who, as workers, may be subject to animus when seeking work. Lack of access to goods and services is the biggest cost associated with licensing, and vulnerable populations bear the brunt of these costs. An ideal licensing reform would increase access without lessening the benefits of licensing. In the following Parts, we consider how licensing reform has been attempted in the past and provide examples for future reform that follow this structure.

II. Stalled and Successful Licensing Reforms

In a 2022 report by the U.S. Department of Treasury, the Biden administration named licensing as a source of decreased labor market competition.[137] The report states that many workers are “subject to excessive occupational licensing requirements that impede their ability to switch jobs across states or their ability to enter a new occupation.”[138] Licensing, among other labor market constraints such as employer monopsony power, non-compete clauses, and misclassification of independent contractors, can weaken the macroeconomy and worsen both firm and worker welfare. The report also notes that “[l]ack of labor market competition contributes to high levels of income inequality,” suggesting that women and workers of color in low-wage occupations bear the brunt of anti-competitive labor market practices.[139] In response, the Biden administration issued an executive order requiring federal agencies to investigate licensing regulations, among other policies, for their anti-competitive effect.[140]

After the report’s release, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) proposed a rule that would make non-compete clauses unenforceable nationwide.[141] The FTC and Department of Labor began a collaboration to end unfair and deceptive acts and practices that undermine labor market competition, naming misclassification of independent contractors and one-sided contract terms as specific targets.[142] Under the Biden administration, the Department of Labor made it a priority to protect employees who are barred from suing their employers due to mandatory arbitration agreements.[143] In contrast, licensing reform saw no action despite public outcry.[144]

This Part investigates why some reform proposals have succeeded while others have stalled. To begin, we describe the long history of proposals to limit or dismantle licensing regimes. Many of these efforts faced pushback from both licensed workers and licensing authorities. Despite these challenges, there is one success story where an industry limited the power of an entrenched licensing authority: the expansion of advanced practice nursing, which curbed the dominance of medical doctors and the American Medical Association (AMA). We then explain how this example can be generalized to address challenges created by licenses across industries.

A. Stalled Proposals for Licensing Reform

A long literature crossing multiple fields has criticized the growth of occupational licensing. Legal scholars have discussed the role licensing has played in limiting the freedom to contract and have proposed that licensing regimes should be subject to antitrust scrutiny.[145] Sociologists have noted that licensing can be a mechanism of closure, restricting access to a community and enabling exclusion of disadvantaged populations.[146] Milton Friedman warned in Capitalism and Freedom that licensing could have negative effects by restricting the availability of professionals such as medical doctors.[147] Since then, economists have shown multiple examples where licensing restricts entry without a commensurate increase in the quality of workers entering an occupation.[148]

Critics of occupational licensing have called for a multi-pronged approach to limit its harms. First, some proposals have centered around holding licensing boards accountable for overly protectionist policies. Second, scholars and policymakers have proposed to erode the exclusivity of licenses by harmonizing standards across states, allowing expedited entry into certain industries for specific populations, and introducing regulatory barriers to slow the increase in licensing authorities’ power.[149] Third, the most radical proposals have called for repealing licenses in favor of less onerous regulations,[150] using federal power if necessary to undermine state law.[151]

Aaron Edlin and Rebecca Haw summarize the first approach and argue that antitrust scrutiny of licensing boards will be most effective in limiting the harms of licensing. They liken licensing boards to cartels because of the boards’ anti-competitive practices, which limit entry of potential workers and raise costs to consumers without a commensurate increase in quality.[152] The authors chronicle the significant increase in licensing beyond historically regulated professions, such as doctors and lawyers, to services like African-style hair braiding and eyebrow threading, which have traditionally operated without licenses. They describe how the Supreme Court has provided immunity to licensing boards from federal antitrust liability as long as a court finds the board’s policies coextensive with state action. Given these immunity defenses, the only avenues of relief plaintiffs can pursue are due process and equal protection claims under the Fourteenth Amendment.[153] However, constitutional challenges are rarely won because licensing boards only need to show their action is rationally related to any legitimate state interest.

Edlin and Haw argue that antitrust law, as opposed to constitutional law, better addresses harms to consumers and advocate imposing Sherman Act liability on state boards.[154] They propose a three-prong test which balances the benefits of a licensing restriction (e.g., ameliorate information asymmetry) against its anti-competitive costs. Under this framework, courts must consider whether there is a legitimate reason for the licensing restriction, analyze the fit between the restriction and the problem, and inquire into less restrictive alternatives.[155] This analysis would require state boards to justify their licensing restrictions by demonstrating a proportionate benefit for consumers.

Rebecca Haw Allensworth’s fifty-state survey finds that self-regulated licensing boards pose a serious threat by raising prices, limiting employment, and reducing the availability of services, which cost consumers approximately $116 billion annually.[156] The survey, which examines membership in 1,790 state occupational licensing boards, finds that 85 percent of licensing boards are statutorily required to be made up of a majority of practitioners with licenses issued by the board itself.[157] Professional membership power is also strengthened by special voting rules that relegate nonprofessional members to nonvoter status and practices that permit long-time vacancies of nonprofessional member seats.[158]

In 2015, the Supreme Court opened up state licensing boards to antitrust liability in North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission.[159] In North Carolina, state law mandated that six of the eight members of the State Board of Dental Examiners must be licensed dentists.[160] One seat was reserved for a dental hygienist, and the last seat was to be occupied by a “consumer” appointed by the Governor.[161] Dentists began whitening teeth in the 1990s. By the early 2000s, non-dentists were also providing teeth whitening services but at a lower price.[162] Several dentists complained to the Board about the rise in competition for teeth whitening. The Board ultimately issued at least forty-seven cease-and-desist letters to non-dentist teeth whitening service providers and sent letters to mall operators advising they evict violators from operating in their malls.[163] In 2010, the FTC filed an enforcement action against the Board, alleging its actions preventing non-dentists from providing teeth whitening were anti-competitive and unfair methods of competition that violated section 5 of the FTC Act.[164] The question presented to the Court was whether federal antitrust regulation protected the Board’s actions through state-action immunity.[165] The Court held that state boards controlled by active market participants may only enjoy state-action immunity if their actions are “actively supervised” by the state.[166]

Allensworth writes that the Supreme Court’s decision prompted a flurry of antitrust lawsuits against state licensing boards based on a variety of anti-competitive theories. Some boards were accused of imposing unfair entry barriers, while others were alleged to have suppressed technological advances that threatened existing practitioners’ profits.[167] Despite an increase in antitrust lawsuits, the Court’s ruling raises further questions about what “controlled by ‘active market participants’” might look like in a “‘mixed’ board” of professionals (e.g., dentists and hygienists constitute a majority but each group in itself does not).[168] Additionally, the Court’s jurisprudence on what constitutes adequate supervision by the state is significantly less clear.[169]

Separate from legal uncertainty, state boards may see membership changes as a safer route to immunity than seeking state supervision in order to avoid public scrutiny.[170] Despite the apparent success in holding licensing boards accountable for anti-competitive conduct, the real impact of North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners has been limited. A growth in active supervision and a subsequent expansion of “state action” immunity have attempted to insulate licensing boards from liability.[171]

Since the Supreme Court case, scholars and policymakers have shifted their attention to proposing limits on the exclusivity of licensing. Organizations such as the Cato Institute have proposed a more drastic solution by stopping all new licensing rules and repealing all regulations that fail a cost-benefit analysis.[172] The Cato Institute has also argued that states should establish independent “sunset reviews” for all licensed professions, where states perform cost-benefit analyses on all current licensing requirements and repeal those that do not generate overall net benefits.[173] In lieu of licensing regulations, the Cato Institute has advocated for the use of market mechanisms to measure an individual’s qualifications. For example, one such mechanism would be a voluntary certification, where individuals can complete a certification to build their credentials for potential employers, but there is no restriction on uncertified workers in an industry.[174] Certification has been lauded as a less restrictive alternative to licensing, since uncertified workers who wish to enter a field cannot be sued by their competitors. Instead, consumers decide whether certification is important to them, allowing workers to distinguish themselves either through certification or other means. For professions where safety is important and certification may be perceived as risky, the Cato Institute has called for states to increase interstate mobility by allowing individuals to carry over their licenses without having to satisfy a new state’s requirements.[175]

The Brookings Institution has similarly proposed that state agencies conduct cost-benefit analyses, focusing on evaluating new occupational licensing requirements. Unlike a full repeal of licenses that fail cost-benefit tests, Brookings has advocated for a more gradual process where the federal government establishes a working group based on expertise in data analysis and policy.[176] This group would then create a set of best practices for regulated occupations and provide financial incentives, such as federal grants, for states to adopt them.[177] It has also suggested that professions, like interior designers, auctioneers, and ballroom dance instructors, that do not pose sufficient risk to health and safety should be reclassified so that they are regulated through certifications or registrations.[178] Like the Cato Institute, the Brookings Institution has also proposed greater reciprocity between states so that license holders do not need to bear additional licensing costs when they move to a different state.[179]

At the federal level, Congress and various presidential administrations have put forth several reforms to improve state licensure. A Joint Economic Committee report proposed requiring state licensing boards find less restrictive alternatives to licensing to maintain immunity from federal antitrust laws.[180] The Obama administration published a framework for policymakers incorporating a number of best practices advanced by the Brookings Institution to gradually reform licensing.[181] For example, the report called for comprehensive, independent cost-benefit assessments of licensing laws, consideration of less restrictive alternative systems (e.g., voluntary state certification), and alignment of licensing requirements across states.[182]

The first Trump administration issued an executive order supporting reforms enacted by states that required licensing boards adopt the least restrictive criteria to licensing and be subject to active supervision by a governmental agency.[183] It also directed all heads of agencies to submit reports to the Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy, and the Director of the Office of Intergovernmental Affairs (IGA) identifying state and local governments with policies consistent with the executive order and recommending actions to reward those jurisdictions.[184] Most recently, the Biden administration issued an executive order emphasizing the threat of excessive market concentration, especially as the United States emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic. It required agencies to review their policies and enforce rules to maximize competition within regulated entities.[185]

Despite the chorus of voices advocating to limit or dismantle licensing regimes, little progress has been made.[186] Industry insiders have pushed for more protectionist regimes and have guarded against attempts at reform.[187] Even reform proponents have admitted that licensing creates some benefits, complicating attempts at full repeal.[188] Although some small-scale state reforms have passed, federal gridlock provides little assurance of widespread and meaningful change.[189]

B. An Alternate Approach: The Healthcare Success Story

This Article proposes a way out of the gridlock that has dogged licensing reform. To provide general lessons about implementing effective changes to licensing, we look to the famous example of advanced practice nurses who were viewed as emerging competition to medical doctors. Importantly, we propose an expansion of licensing that does not directly threaten incumbent license holders. The introduction of an alternative license in the same industry as another license allows consumers more choice while empowering a new group of workers.

The economic intuition behind expanding licensing is simple. Licensing authorities that control all entry into a particular market function as monopolies.[190] They have an incentive to limit their supply of labor to keep wages high, harming both potential entrants and consumers. Introducing a competing license within the same industry shifts the labor market to a duopoly. Consumers can choose which license they prefer and hire workers with that qualification. Moreover, a new group of workers can enter an industry that was previously off limits. Introducing an alternative license has the potential to benefit both consumers and underrepresented workers and can sidestep pushback from incumbents who benefit from controlling the licensing structure.

A famous example of this approach in the United States is the growth of advanced practice nursing in the medical field.[191] Access to healthcare provided by medical doctors has been limited over the past several decades.[192] Commentators blame this shortage on the AMA’s overly protectionist policies that restricted the number of doctors qualified to practice in the United States, raising wages but denying care to needy patients.[193]

Since the 1990s, alternate forms of medical licensing have grown in popularity and in their scope of practice, often overlapping with doctors of medicine (MD). These licenses included non-nursing licenses, such as Physician Assistants (PA), as well as several nursing licenses, including certified Nurse Practitioners (NP), Certified Nurse Midwives, Clinical Nurse Specialists, and Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetists.[194] In many cases, advanced practice nurses must work collaboratively with doctors and stay within a prescribed scope of practice to meet the requirements of their license. However, in “full-practice” states, NPs can prescribe medicine, order lab work, and complete procedures within their specialty without an MD’s supervision.[195] Allowing advanced practice nurses to provide care alongside medical doctors expands the number of highly skilled professionals from whom a patient can receive care. For this reason, California recently transitioned to being a full-practice state, with the goal of increasing the availability of healthcare in underserved areas.[196]

This example showcases how expansions of licensing can generate important benefits. Licensing can enable the creation of a well-defined interest group, which can then fight protectionist policies imposed by incumbents. Importantly, in 1973, the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNP) was established, and soon after, the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties (NONPF) and the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners (AANP) were formed.[197] These organizations provided the institutional power needed to provide training and educational resources within the group as well as lobby legislators to pass bills supporting the profession.

For example, the NONPF published several reports in the 1980s on program standards for NP curricula and hosted an annual conference that quickly became a vital convening of NP faculty.[198] In 1987, the AANP conducted a survey of its membership to measure medical malpractice liability insurance coverage across the organization and helped members find affordable coverage.[199] The AANP served as a nationwide coalition of various NP groups and advocated for broader federal changes to address challenges NPs faced. At the AANP’s national meeting in 1996, members raised concerns about struggles obtaining reimbursement for services, and the AANP quickly mobilized around the issue.[200] The AANP raised funds to hire a lobbying firm and successfully pushed for the Primary Care Health Practitioner Act of 1997. Congress ultimately passed this legislation in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, thus granting NPs provider status to bill Medicare directly for all services provided, a right historically reserved for MDs.[201]

Another benefit of licensing advanced practice nurses is the legitimization of the profession. Despite having achieved Medicare provider status,[202] NPs’ path to public legitimacy required developing a shared identity, mobilizing for shared needs, and taking political action. NPs originated in the mid-1960s when Henry Silver, a physician, and Loretta Ford, a nurse, developed the first NP training program at the University of Colorado.[203] Nurses and physicians initially opposed the creation of NPs, with some nursing leaders arguing that NPs would take over nursing education and physicians casting the new group as providing “bad doctoring.”[204] However, Silver and Ford recognized that the existing number of physicians was not meeting the demand for primary care and that increasing the nursing supply by expanding training and educational resources was necessary to obtain the public’s trust.[205]

Despite the criticism from incumbents, the number of NP programs grew—reaching over sixty-five programs in 1973 and over two hundred by 1980[206]—and NPs continued to pursue different strategies to legitimize their profession. NP academics and practitioners developed standard curriculum guidelines for NP education and conducted scientific studies showing the efficacy and safety of NP care.[207] Colleges and universities also developed certificate programs and master’s level degrees, which prepared NPs for academic careers.[208] Then, in 1994, the New England Journal of Medicine published a study finding that the quality of primary care provided by NPs was equal to or even higher than that provided by doctors.[209]

Perhaps the most important benefit of such expansion is the role licenses can play in forcing incumbent boards and trade groups to release their chokeholds on a market. The healthcare example demonstrates how creating a license outside the AMA’s control allowed a new group of workers to organize. Today, states grant power to Boards of Nursing or Boards of Medicine to set the licensing requirements for medical professions, including NPs.[210] Despite their nonprofit status, these organizations have the same incentives as the AMA to limit the supply of new entrants into these lucrative professions.[211]

Benjamin J. McMichael writes about ways NPs engage in political spending to increase their scope of practice.[212] The paper shows that NP groups spend more on lobbying in states with laws granting them greater autonomy.[213] This extends to hospital groups that have an interest in reducing costs by allowing PAs to perform more tasks independent of physician oversight.[214] When hospital groups increase their political spending, legislatures pass more laws that expand PA autonomy.[215] This study further finds that long-term political lobbying is most important, because spending measured over four years has greater and more statistically significant effects than spending measured over shorter periods.[216]

Despite the benefits of introducing and expanding advanced practice nurse licenses, several structural issues remain. Advanced practice nurses have had differential success challenging medical doctors’ dominance across different healthcare markets. Restrictions on NP scope of practice vary heavily across states.[217] Many states are “full practice” states where NPs are unrestricted, suggesting that nursing degrees could eventually replace some MD degrees.[218] However, states with narrow NP scopes of practice often put MDs in charge of NPs, further cementing MD power over the healthcare market.[219]

Moreover, though advanced practice nursing provides an easier path to entry than the MD path, barriers remain that allow the current hierarchy to persist. First is the high cost of training. When an expensive degree is necessary for a lucrative career, the industry may give in to credentialism and inadvertently replace substantive learning opportunities with certifications that can simply be purchased without significant investment.[220] Several scholars have studied medical boards and their disciplinary proceedings and found that board discipline has the potential to be effective but is plagued with inefficiency and biases.[221] As in other contexts,[222] critics allege that boards selectively enforce rules in favor of privileged populations.[223] There are no options within the United States for advanced practice nurses to become medical doctors.[224] Both career paths require similar work, including detailed classes covering material on anatomy, physiology, diseases, and body systems, and exams testing that material.[225] Despite the overlap, credentialing authorities on both sides refuse to accept work from the other track to ease the path to licensing.

Advanced practice nursing demonstrates how multiple licenses within the same occupation can prevent monopolistic behavior and promote market competition. The benefit to workers is that they can choose to satisfy the requirements of being a licensed NP rather than an MD, which provides an additional thirty-nine thousand spots in advanced degree programs for students interested in practicing medicine.[226] The benefit to consumers is that they have access to care from NPs as well as MDs, which particularly helps consumers in rural areas.[227] However, there are still costs associated with these programs, including high entry fees and little mobility across licenses. Yet, this licensing reform model creates diverse pathways for workers while maintaining quality and wages and can provide a template for other licensed industries.

C. Diversification Through Licensing

Licensing reform in the style of the healthcare industry has great promise, but historically, negative effects of licensing have disproportionately impacted vulnerable populations.

The story of advanced practice nurses, however, has emerged as a positive example in which licensing improves diversity. The growth of advanced practice nursing has allowed more diverse healthcare workers to treat patients. Researchers find that 93 percent of NPs, compared to 54 percent of primary care physicians, are female.[228] NPs also provide care in high-need areas, serving more rural and urban areas compared to physicians who most commonly practice in suburban areas.[229] Surveys further show that patients cared for by NPs report higher levels of trust than patients cared for by physicians.[230] Notably, older, Black adult patients report high levels of trust in their NPs despite reporting moderate levels of mistrust in the healthcare system.[231] These findings show how the rise of NPs increases provider diversity as well as improving access to high-quality services for underserved communities.

The growth of advanced practice nursing also combats wealth inequality by lowering the financial cost of entry into healthcare professions. The biggest barrier to practicing medicine is completing the competitive training, including entry requirements, examinations, and practice experience. MD degrees are highly selective and take four years after an undergraduate degree, followed by a minimum of three years of residency. The total cost of an MD, after an undergraduate degree, averages $200,000.[232] On the other hand, NPs follow their undergraduate training with a two-year master’s program, followed by a two-year doctor of nursing practice degree program, meaning that their training can take three years less than an MD’s training.[233] The total cost of an NP’s graduate training averages less than $100,000, about half the cost of medical school.[234] As a path to practicing medicine, NPs have easier access than MDs.

That being said, advanced practice nursing degrees are still costly and highly competitive. Four-year undergraduate degrees are themselves difficult to access and complete successfully, especially for disadvantaged populations.[235] Roughly sixty-five thousand students wishing to enter nursing education had their applications rejected by nursing programs, with fifty-five thousand of those turned away at the undergraduate stage and an additional ten thousand at the graduate level.[236] Moreover, NPs enter the workforce with an average of more than $150,000 in student loan debt.[237] Highly qualified healthcare workers are less likely to be racial or ethnic minorities, and less likely to come from a low-income or first-generation college background.[238] Therefore, significant work still needs to be done to make medical careers accessible to disadvantaged workers.

Advanced practice nursing is a useful model for transforming occupational licensing from a source of inequality into a powerful weapon against inequality. Replicating its successes and remedying its failures would benefit workers and consumers across occupations. In particular, advanced practice nursing successfully expanded healthcare access and provided new professional roles, disproportionately benefiting vulnerable consumers and workers. At the same time, the new licenses were still costly to access and put these jobs out of reach for workers with the lowest levels of wealth and opportunity. To describe how licensing reform can work in more accessible professions, we introduce a novel empirical example supporting our policy proposals.[239]

III. Food Businesses as a Case Study

Industries that provide necessities, such as food, are essential to consumers and workers alike, making them important case studies for policy reform. Food, in particular, has powerful effects on inequality.

Inequality in access to quality food is pervasive and precipitates or worsens nearly every other form of social inequality in modern society.[240] Prior to 1900, food production and preparation were largely unregulated.[241] Since the introduction of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the growth, harvesting, preparation, and sale of food have steadily become more heavily regulated.[242] Despite well-intentioned government action, however, scholars and policymakers have noted that access to high-quality nutrition did not universally increase during that time.[243] Instead, food became a source of stratification, separating privileged and disadvantaged populations.[244] Moreover, neighborhoods that tended to be poor or Black had less access to healthy food, resulting in “food deserts” across the United States.[245] These inequalities persist throughout the food ecosystem, with minority workers facing fewer opportunities and lower wages than other workers.[246]

We collect novel empirical data to study whether expanding food business licensing can fight these inequalities. Below, we describe the evolution of food licensing and its intersection with minority and underprivileged populations in California, culminating in California passing its Homemade Food Act in 2012. We then highlight how food licensing can reduce inequalities for both food producers and consumers. Next, we present our data and the results of our analysis. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings for the design of licensing regimes generally.

A. New Frontiers of Food Business Licensing

1. The Food Freedom Movement and California’s Homemade Food Act

Food available for commercial purchase must meet state and federal requirements. States have dominion over food safety and distribution regulations under their broad policy powers.[247] At the same time, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides a model Food Code as federal guidance, recommending best practices to prevent foodborne illnesses, but it is not binding unless a state or local government incorporates it into their statutes.[248] Every state except California has adopted some version of the Food Code.[249] The FDA defines all places where food is produced for retail as “food establishments” and traditionally excludes home kitchens from this category.[250] However, the FDA Food Code has historically provided exemptions for foods prepared in home kitchens that are deemed low-risk for developing harmful pathogens and are sold at religious or charity bake sales.[251]

Food industry participants were not satisfied with this limited exemption. A bipartisan movement began to expand consumers’ access to home-prepared foods. Known in many states as the “Food Freedom” movement, this bipartisan push to expand food production was supported by small farmers, home cooks, and consumers’ demand for farm-to-table foods.[252] In response to growing demand from home food producers, states passed laws exempting low-risk foods made in home kitchens from the “food establishment” definition through cottage food laws or by creating separate home kitchen regulations.[253] Examples of cottage foods include baked goods without meat or cream, candies, infused alcohols, and vinegars, all of which are relatively shelf stable and unlikely to result in illness due to food mishandling.[254]

Some states have increasingly moved towards allowing more types of cottage foods by adding items to their cottage food list.[255] Others have taken a more expansive approach by permitting all foods, except those explicitly listed in the statute, to be made in home kitchens.[256] Styled as food freedom laws, these are often separate statutes that provide broad exemptions from regulation.[257] For example, Wyoming has the most open food freedom law, which exempts homemade food not containing meat (although poultry is permitted under certain circumstances) from all state licensure, inspections, labeling, and packing requirements.[258] Utah’s Home Consumption and Homemade Food Act similarly exempts home-kitchen operators from licensing and inspection requirements, though it does limit where food can be sold.[259]

Currently, nearly all fifty states have passed some type of cottage food law that permits home food producers to sell a limited type of items at farmers markets and grocery stores.[260] In California, the first iteration of the state’s Homemade Food Act was passed by the state legislature in 2012.[261] The law created a cottage food operations provision within the California Food Code and established two types of licenses: Class A (direct sales) and Class B (direct and indirect sales).[262] It also delegated the duties to permit and inspect home kitchens to counties and cities.[263] The law stated that its purpose was twofold: to provide greater opportunities for entrepreneurial development that could strengthen local economies and to increase access to sustainable and healthy food options for low-income and rural communities.[264] The statute initially capped gross annual sales at $50,000,[265] which legislators later increased to $75,000 for Class A and $150,000 for Class B licensees.[266] The California Department of Public Health maintains a list of approved cottage food categories, and cottage food operators may request that the department consider adding a food product or category to the list.[267]

California’s 2012 law does not allow home cooks to sell prepared hot foods.[268] This restriction was partially lifted in 2019, when California introduced the MEHKO permit.[269] MEHKO permits were issued to home kitchens inspected by public health authorities and required permit holders to undergo significant food handler training.[270] Permit holders could then legally sell temperature-controlled foods, essentially operating a restaurant from their homes.[271] However, MEHKO permits came with some barriers. Most importantly, counties had to opt in to begin issuing MEHKO permits.[272] As of May 2022, when our data were collected, only nine counties had begun issuing MEHKO licenses: Riverside, Alameda, San Mateo, Santa Barbara, San Diego, Solano, Imperial, Lake, and Sierra.[273] Total sales were initially capped at $50,000, and the cap has increased by less than $10,000 in the subsequent four years.[274] Home cooks can serve only thirty meals per day, or sixty meals per week, and must sell food directly to a consumer the same day it is cooked.[275] Despite these restrictions, California’s MEHKO law is one of the most permissive in the country and represents the first attempt of its kind nationwide.

2. Disparate Impact on Ethnic Foods

The regulation of food production intersects with the culture and identity of both food producers and consumers, highlighting the role that law can play in the inclusion (or exclusion) of minorities in the food ecosystem. Historically, many expansions in food availability have faced pushback due to potential safety issues.[276] Ethnic foods face particular challenges due to widespread ignorance of cultural food practices.[277] Food law and policy discussions often exclude ethnic foods, resulting in a limited understanding of both the benefits and costs of added food variety.[278]

Coined the “Great Taco Truck War” by Time magazine, the legal fight between food trucks and Los Angeles County exemplifies the challenges ethnic food producers face.[279] In 2008, Los Angeles County passed an ordinance prohibiting food trucks from parking in one spot for more than an hour.[280] Violators faced a $1,000 fine, six months in jail, or both.[281] Officials defended the ordinance, citing several complaints from food establishments about unfair competition from food trucks and complaints from property owners about noise and littering.[282]

But the backlash from food truck operators, residents, and food writers was swift and strong.[283] In Los Angeles, taco trucks provide more than food—they represent the city’s cultural richness and immigrant origins.[284] For example, taco trucks sold more than tacos and burritos generally associated with these vendors; they also infused Korean, Chinese, Vietnamese, and other culinary influences.[285] Some trucks specialized in Brazilian, Indian, and other international cuisines, while others focused on desserts or vegan and vegetarian offerings.[286]

A Los Angeles Superior Court judge ultimately invalidated the ordinance on the basis that it was not rationally related to a government purpose, was preempted by state law, and unconstitutionally discriminated against food trucks for the benefit of restaurants.[287] Despite the legal victory, this event illuminated the tensions between those who see food trucks as a source of affordable food associated with various immigrant cultures and those who see them as foreign, unsanitary, and public nuisances.[288]

The battle over health and safety standards for certain Asian foods provides another example of the regulatory tension around ethnic foods. In July 2009, public health inspectors descended on Kun Wo Food Product Inc., a rice noodle manufacturer that distributes its products to over one hundred Bay Area restaurants.[289] The inspectors issued a citation for violating a state regulation requiring certain foods to be held at or below 41 degrees or above 140 degrees Fahrenheit.[290] Later, Willa Liu, daughter of one of the company’s owners, would explain that they could not follow the state regulation because refrigerating the noodles would turn them brittle and inedible.[291] This event was highly publicized, drawing attention from state legislators, such as Senator Leeland Yee, who told reporters that the company was a victim of cultural misunderstanding and overzealous inspectors.[292]

In response, during the 2009–2010 session, Yee proposed SB 888 Food Safety: Asian Rice Based Noodles.[293] The bill sought to exclude rice-based noodles from existing temperature regulations and allow the noodles to remain at room temperature for up to four hours.[294] The bill argued “any change in production would change a standard used by Asian communities for thousands of years.”[295] The fight over noodles was also ultimately resolved with then-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger signing SB 888 into law in 2011.[296]

SB 888 was modeled after AB 187, which permitted vendors to sell Korean rice cakes that have been at room temperature for up to twenty-four hours.[297] At the time, supporters successfully argued that once rice cakes were refrigerated, they would harden and become less marketable and desirable to customers.

This was not the first time food safety laws had clashed with businesses selling traditional Asian foods. Vendors had previously argued that dishes like Korean kimbap (rice wrapped in seaweed and stuffed with meat or vegetables) and Vietnamese goi cuon (cooked shrimp wrapped in rice paper) need to be sold at room temperature.[298] Though they risked citations, vendors stated that refrigeration would harden the food to the extent that customers would not purchase it at all.[299] Inspectors, however, argued that food safety laws were clear—room temperature allows hazardous bacteria to grow in food and sicken people.[300] One program manager at the Orange County Health Care Agency said, “Bacteria know no cultural bounds . . . . Everybody coming from the old country, they bring their cultural baggage with them, and sometimes the baggage doesn’t make good health safety sense.”[301] Tracing a foodborne illness to its source is notoriously difficult, further escalating the debate between food vendors and public health officials.[302]

SB 888 was part of a growing movement to address gaps in food safety laws that prohibited the sale of Asian foods traditionally sold at room temperature. Several years before SB 888 was introduced, AB 2214 directed the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to evaluate whether traditional Asian foods, specifically banh chung, banh tet (Vietnamese rice cakes), and moon cakes, could stay out at room temperature longer than four hours before accumulating harmful bacteria.[303] AB 2214, like SB 888, attempted to balance food safety with traditional consumption practices.[304]

Although this study contained mixed results, in 2016, then-governor Jerry Brown signed SB 969, which permitted the sale of banh tet and banh chung at room temperature for up to forty-eight hours and removed rice cakes from the category of potentially hazardous foods.[305] However, the bill required labels disclosing the date and time of production and warning that rice cakes must be eaten within twenty-four hours.[306]

Rules that purport to protect consumers from illness have erected barriers for ethnic food producers and consumers to trade lawfully. So far, issues of ethnic food regulation have been considered one by one, for each type of food. The expansion of home food licensing and MEHKO permitting, in particular, could increase access to ethnic foods on a larger scale, since each cook can decide to offer a highly varied menu.

B. Empirical Evidence on Food Producers

We shed light on the interaction between food regulation and identity by collecting data on food business license holders and identifying their demographic characteristics. To do so, we submitted public record requests for lists of licenses to county environmental health agencies beginning in March 2022.[307] Because responding counties tended to be the largest, we collected data from counties covering more than 90 percent of California’s population. Key data for our analysis include current license holders’ names, addresses, and the type of food facility they operate.[308] Based on this information, we use a variety of datasets to augment the information on these food businesses.

First, we create an estimate of each license holder’s race, ethnicity, and gender based on their name and location, using a technique called Bayesian Improved First Name Surname Geocoding (BIFSG), which the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) uses for fair lending analysis.[309] The method uses Census data on the racial composition of each Census block in the United States to guess the probability that an individual living in that block belongs to a specific race.[310] Then, the method updates the guess based on the individual’s surname and first name.[311] We further adapt the standard methodology by using the Census’s Workplace Area Characteristics data to estimate race by employment location, rather than residence, to account for workers’ commute patterns.[312] Finally, we use data from the Social Security Administration on names by gender to estimate the probability that an individual is female or male.[313]

We then further expand the available information about each food business by merging with a comprehensive dataset on all public and private companies registered in the United States, gathered by Dun & Bradstreet and packaged by Mergent.[314] For the 40 percent of food businesses for which Mergent has information, we can observe the year of incorporation, number of employees, and other registration information. Though the merged sample is incomplete, it includes information on all types of businesses, including traditional food facilities, mobile food facilities, cottage food facilities, and MEHKOs. The full sample of licenses in California contains information for just over 197,000 businesses, of which 13,600 are mobile food facilities, 6,700 are cottage food facilities, and 200 are MEHKOs. The Mergent sample has information for just under 89,000 businesses, of which 2,000 are mobile food facilities, 750 are cottage food facilities, and 3 are MEHKOs. We report characteristics of these license holders below.

Figure 1: Year of Incorporation of License Holders - Mergent Sample