Rights Violations as Punishment

Is punishment generally exempt from the Constitution? That is, can the deprivation of basic constitutional rights—such as the rights to marry, bear children, worship, consult a lawyer, and protest—be imposed as direct punishment for a crime and in lieu of prison, so long as such intrusions are not “cruel and unusual” under the Eighth Amendment? On one hand, such state intrusion on fundamental rights would seem unconstitutional. On the other hand, such intrusions are often less harsh than the restriction of rights inherent in prison. If a judge can sentence someone to life in prison, how can a judge not also have the power to strip someone of the right to marry, or speak, as direct punishment? Surprisingly, as this Article reveals, existing law offers no coherent explanation as to why rights-violating punishments somehow escape traditional constitutional scrutiny. Yet the question is critical as courts—often in the name of decarceration—increasingly impose non-carceral punishments that deprive people of constitutional rights.

Table of Contents Show

Introduction

To what extent can a judge deprive someone of fundamental constitutional rights as punishment for a crime and in lieu of prison? The question is not merely theoretical. For the 4.5 million people who are subject to criminal court control but not incarcerated, criminal punishments routinely restrict their rights to travel, marry, bear children, worship, socialize, and protest.[1] People under criminal court supervision are frequently required to provide DNA samples to law enforcement, use devices that measure drug and alcohol use, or wear GPS- and microphone-equipped ankle monitors that record and track their precise location 24/7, sometimes for months or years at a time.[2] And as part of non-carceral punishments, courts commonly order people to participate in religious drug treatment programs like Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) or others that may require individuals to sign self-incriminating acceptance of responsibility statements.[3]

These punishments, and others like them, highlight two interrelated and often conflicting phenomena in criminal law: increased reliance on “alternative” non-carceral punishments, and the increasing degree to which these punishments strip people of constitutional rights. Although the deprivation of rights has always featured prominently in all forms of punishment, advances in surveillance technology, along with the influence of private “community corrections” entrepreneurs, have created an even more invasive web of rights-restricting non-carceral punishments.[4] While these punishments are often imposed in the name of decarceration, they instead risk reinforcing what Professors Amanda Alexander and Reuben Jonathan Miller call “carceral citizenship,”[5] a status that legitimates the legal exclusion of historically subordinated groups and reinforces social-legal hierarchies based on race, class, disability, and gender.

This expanded landscape of non-carceral punishments surfaces a lurking but critical question: why do rights-violating punishments escape traditional constitutional review that applies outside of the punishment context?[6] On one hand, the “right to have rights” is “not a license that expires upon misbehavior,”[7] and non-carceral punishments that restrict rights seem like classic state actions that are unconstitutional “unless . . . narrowly tailored to [meet] a compelling state interest.”[8] On the other hand, the rights deprivations inherent in non-carceral punishments are often less harsh than the deprivations inherent in prison. If a judge can sentence someone to life in prison, how can a judge not also have the power to strip someone of the right to marry, worship, or speak as direct punishment?

Punishment jurisprudence offers clues but no clear answer. A prison sentence, after all, involves the obvious deprivation of liberty, and people in prison generally lose rights that are “inconsistent with” incarceration.[9] Likewise, courts uphold exploitative prison labor and felony disenfranchisement as legal punishments explicitly permitted by the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments.[10] And the deprivation of still other rights, such as the right to bear arms or serve on a jury, is justified as a collateral consequence of a criminal conviction.[11] But are non-carceral punishments that restrict religious practices or intimate relationships, for example, justified merely because they are punishment or rather because they pass First Amendment and substantive due process scrutiny? Likewise, is tracking a person’s location 24/7 through a GPS ankle monitor permissible because it is punishment, or because it is considered a “reasonable” Fourth Amendment search?

In short, is there something special about punishment that justifies what I refer to as “punishment exemption,”[12] the assumption that non-carceral punishment is exempt from traditional constitutional scrutiny? The question of punishment exemption is not limited to non-carceral punishments, though the problems are most stark in that context. People in prison—like people subject to non-carceral punishments—also lose rights, though there is a more robust, albeit often inadequate, legal regime to evaluate such deprivations.[13] No such legal framework exists with respect to non-carceral punishments. This Article engages these murky questions and offers a simple, if unexpected, answer: punishment is not exempt from the Constitution. All punishment, including imprisonment, is state action subject to traditional constitutional review.[14] Properly understood as such, many non-carceral punishments, along with some prison sentences, are unconstitutional, even if not cruel and unusual. How punishment exemption has nonetheless flourished, and its implications, is the focus of this Article.

Certainly, part of the puzzle is courts’ failure to recognize, much less appreciate, the rights-stripping nature of non-carceral punishments. Because non-carceral punishments are generally viewed as “better” than prison—and they often are—the analysis of their impact on fundamental rights often stops there. But better-than-prison is a low threshold and fails to resolve the question of what constitutional scrutiny is due, much less whether these punishments are sound or humane policies.

Drawing on my ongoing and original empirical research on the operation of non-carceral punishments, this Article exposes the web of rights-violating punishments that would typically be considered unconstitutional outside of the punishment context. To be sure, as alternatives to incarceration gain in popularity, scholars and activists have raised alarm about the restrictive and invasive nature of non-carceral punishments and how they reproduce the racialized carceral state, even if to a lesser degree than physical incarceration.[15]

My own prior experience defending young people in juvenile delinquency court reinforced these concerns. I saw firsthand how non-carceral punishments—such as house arrest, therapeutic courts, halfway houses, and GPS ankle monitoring—were not so much alternatives to incarceration but alternative forms of incarceration.[16] Even the label “non-carceral” is imperfect as it fails to capture the myriad ways that distinctly carceral logic defines purported alternatives to incarceration.[17]

Overlooked by scholars and courts alike, however, is the legal doctrine—and lack thereof—that has facilitated the proliferation of non-carceral punishments that restrict basic rights. Neither the text of the Constitution nor basic constitutional principles offer doctrinal support for exempting state action in the form of non-carceral punishment from traditional constitutional scrutiny.[18] Indeed, in his dissent in Samson v. California, in which the majority upheld suspicionless searches of people on parole, Justice Stevens cautioned that the Court has never “sanctioned the use of any search as a punitive measure.”[19] Following this logic, a small handful of courts appear to reject punishment exemption and subject at least some non-carceral punishments to traditional constitutional scrutiny, but they are the rare exception.[20]

More often, courts ignore the rights-stripping nature of non-carceral punishments, rely on the purported consent of the person subject to the punishment, assume the restrictions are merely “conditions” and not punishment, or uphold rights restrictions that “reasonably relate” to rehabilitation or public safety, a standard imported from the prison context.[21] These deferential approaches are consistent with Justices Scalia and Thomas’s view that states should be afforded deference “to define and redefine all types of punishment, including imprisonment, to [include] various types of deprivations”[22] and that criminal conduct properly extinguishes the right against unwarranted confinement and liberty.[23] In a dissent penned by Justice Thomas and joined by Justice Scalia, the Justices explained that there is no general fundamental right to freedom from bodily restraint; if there were, “convicted prisoners could claim such a right,” and “we would subject all prison sentences to strict scrutiny[, which] we have consistently refused to do.”[24] Under this view, it is only the Eighth Amendment that limits punishment.[25]

The problem, however, is that there is no obvious legal basis to exempt punishment from traditional constitutional scrutiny that would otherwise apply.[26] Not only is consent a questionable legal basis,[27] but the “reasonably related” standard is often inapplicable to the non-carceral setting,[28] and classifying the deprivation of rights as a “condition” or “regulation” and not punishment is likewise legally, and factually, unsound.[29] Perhaps most significant, these deferential justifications do not resolve why rights-restricting punishments are exempt from the constitutional scrutiny that traditionally applies to state action.[30] Rather, as this Article argues, state action is state action regardless of the context. There is nothing exceptional about criminal punishment that makes it immune from standard constitutional scrutiny. Indeed, decades of prisoners’ rights litigation have helped establish that incarceration does not escape constitutional scrutiny simply because it is imposed as punishment.[31] It may be that many long prison sentences or certain types of non-carceral punishments are constitutional, but it is not because they are exempt from traditional constitutional review.

While some progressive legal scholarship understandably questions the efficacy of rights-based frameworks to disrupt the racial and economic inequities endemic to the carceral state,[32] this Article suggests that there is value added in challenging the legitimacy of punishment exemption and exposing its lack of jurisprudential support. On an immediate and pragmatic level, applying greater scrutiny to the deprivation of rights associated with punishment can shrink the carceral apparatus and rein in extreme rights infringements, as well as make visible rights deprivations that currently fly below the radar. A more radical reimagination of the carceral state—in all its permutations—is also in order,[33] and, at the same time, the need to reckon with the current state of punishment law remains.

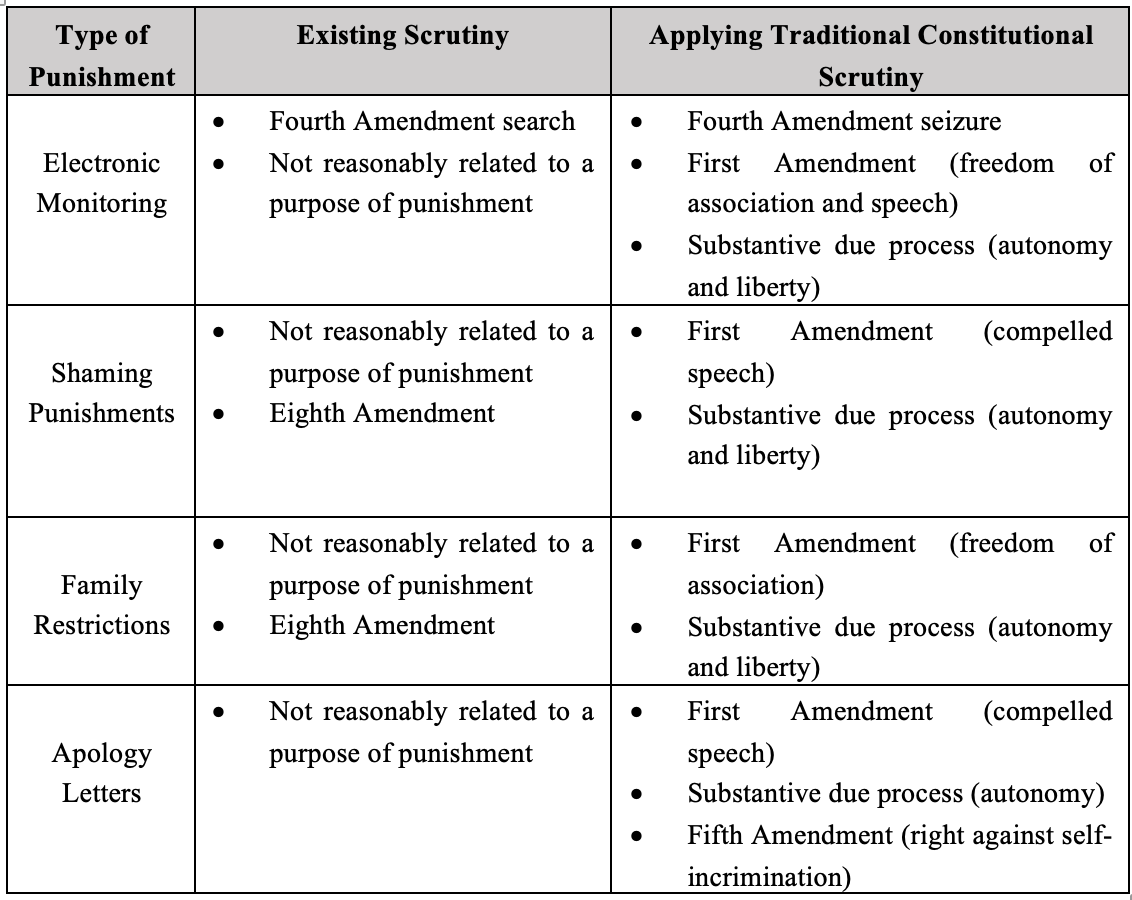

On a broader jurisprudential level, exploring how rights-restricting punishments escape traditional constitutional scrutiny reveals a categorical chasm—and mismatch—between the fields of criminal procedure and constitutional law.[34] The surveillance inherent in electronic monitoring and community supervision, for example, raises not just Fourth Amendment concerns but also implicates First Amendment and substantive due process rights. Likewise, requiring someone to write an apology letter raises First Amendment concerns, but such a requirement could also be viewed as raising Fifth Amendment concerns since an inculpatory statement could be used against them in a later proceeding. Yet, the legal analysis of these practices is routinely siloed, with courts opting to not analyze Fourth Amendment problems as First Amendment or substantive due process problems and vice versa.[35] The disconnect between criminal procedure and constitutional law is neither preordained nor inevitable. In fact, by having law students take separate classes in criminal procedure and constitutional law, the legal academy sends a clear message that criminal procedure is not constitutional law, even though the two fields both focus on constitutional text and amendments.[36] This divide reflects—and may help explain—why criminal punishments are generally not viewed as raising constitutional concerns beyond the Eighth Amendment.

This Article proceeds in four Parts. Drawing on a large and ongoing empirical research project, Part I offers a portrait of rights-restricting non-carceral punishments to bring into focus the scope and impact of punishment exemption. Part II draws on the text of the Constitution as well as foundational constitutional principles to demonstrate the lack of jurisprudential support for punishment exemption. Part III addresses five anticipated objections: first, that prison is more restrictive than most non-carceral punishments yet still perfectly legal; second, that but for non-carceral punishments people would otherwise be imprisoned; third, that consent nullifies the need to address constitutional questions; fourth, that the deprivation of rights is not punishment, but rather a condition or rule; and fifth, that the Eighth Amendment is the only constitutional provision that limits punishment. Part IV explores the implications of applying traditional constitutional scrutiny to not just non-carceral punishment, but all punishment. It explains how restrictions on religion or speech, for example, are unconstitutional punishments unless they pass the applicable First Amendment scrutiny. The Article concludes with lessons for the future of decarceration.

I. A Portrait of Rights Violations as Punishment

As courts and legislators increasingly look to non-carceral punishments—often in the name of decarceration—the lack of jurisprudential support for these rights-restricting punishments comes into sharp focus. Drawing on my original empirical research, this Section shines a light on a few examples of rights-restricting non-carceral punishments, the impact of the restrictions, and how they exemplify the problem of exempting punishment from traditional constitutional review.

A. The Rise of Non-Carceral Punishment

Several forces have contributed to the increased use of non-carceral punishments: bipartisan interest in curbing mass incarceration, advances in surveillance technology, and the influence of the “technocorrections”[37] industry and other private vendors that market “alternatives” to incarceration.[38] Together, these forces, further accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis in prisons and jails, produced an expanded landscape of incarceration alternatives, including therapeutic and (or) mental health courts,[39] electronic monitoring,[40] community service programs,[41] drug courts,[42] restitution centers,[43] residential religious treatment programs,[44] domestic violence and sex offense courts,[45] shoplifting diversion,[46] special court programs for people convicted of prostitution,[47] community courts,[48] treatment centers,[49] and police- or prosecutor-led restorative justice circles,[50] to name just a few.

In general, non-carceral punishments are imposed for low-level felonies, misdemeanors, and non-violent crimes, or for people accused of crimes for the first time.[51] As Professor Issa Kohler-Hausmann describes her experience observing criminal court in New York City, “[s]it in any misdemeanor arraignment or all-purpose part in the city, and you will hear a veritable alphabet soup of programs being offered and accepted as part of case dispositions.”[52] Usually imposed at sentencing, these punishments are often standalone programs but other times take the form of additional conditions or restrictions added onto existing sanctions. People convicted of crimes are most frequently asked to consent to certain non-carceral punishments, even though the court has the authority to impose the punishment regardless of the individual’s consent.[53] While these programs do not involve jail time, they represent what Professors Jonathan Simon and Malcolm Feeley term the “new penology,” which relies on techniques to “identify, classify, and manage” people based on their alleged offenses.[54]

Although there are many examples of non-carceral punishment, this Section focuses on only a few, with the goal of highlighting the ways in which non-carceral punishment escapes traditional constitutional scrutiny. Many of these examples come from my large and ongoing empirical research project examining the operation of punishment outside of prisons.[55] This research involves collecting and analyzing hundreds of agency records (such as rules and internal policies) that govern non-carceral punishment. Taken together, these records paint a vivid picture of carceral practices operating outside of physical prisons. The categories below are approximate, as there is often overlap between programs or different names for the same program depending on the jurisdiction.

1. Probation, Parole, and Supervised Release

Probation, parole, and other forms of court supervision have long been deployed as alternatives to incarceration while also being recognized as punishment.[56] There are currently nearly 4.5 million people on probation, parole, or supervised release.[57] Probation is generally imposed in cases where a defendant is not eligible for a prison sentence or might otherwise be incarcerated but is instead sentenced to probation. Parole, by contrast, is most often provided for by statute and exists as a way for people to complete their prison sentence outside of a prison. In the federal system, federal supervised release is added on at the end of a prison sentence.[58]

The deprivation of rights is a definitional part of court supervision. As other scholars have shown, people on probation, parole, and supervised release are subject to dozens of restrictive and invasive rules.[59] These rules govern all aspects of life: suspicionless searches, random drug testing, collection of DNA samples, court-mandated treatment programs, community service, restrictions on associating with certain people, curfews, and house arrest are all common features of court supervision.[60]

2. Halfway Houses and Work Centers

Throughout the country, people are often sentenced to spend time after a prison sentence at halfway houses, residential drug treatment programs, or work centers. Because people sent to these residential programs are often already on probation, parole, or supervised release, they are subject to multiple sets of rules—the rules governing court supervision and the rules of the program or facility. In most places, the programs are residential, and participants must abide by curfew and are limited in when they can leave and where they can go.[61] In many work and restitution centers, residents are restricted in the use of their income. They are often prevented from having ATM cards and forced to save a certain percentage of their income.[62]

Many of these programs also limit people’s travel rights.[63] For example, a work release center in California forbids residents from leaving the center during the first few weeks of the program.[64] Even after the first few weeks, residents cannot drive a car or leave the center without an approved pass that includes a description of everyone and every place the resident will visit.[65]

Work and restitution centers take different forms. In Mississippi, people are sentenced to restitution centers where, for months (and sometimes years), they work for less than minimum wage and the state collects their pay, giving them only enough money to buy necessities.[66] Likewise, in Oklahoma, people are sentenced to rehabilitation camps where they are required to work for free and often in poor conditions, like in chicken processing plants.[67]

Non-government entities, both for-profit companies and non-profits, operate most halfway houses. The GEO Group, one of the largest contractors for private prisons and electronic monitoring in the country, runs Community Education Centers, which operate almost 30 percent of halfway houses nationwide.[68] The federal government also operates over 150 residential reentry centers with a total capacity of almost ten thousand residents.[69] Several work-release programs—both publicly and privately run—have been criticized for retaliation, arbitrary discipline by staff, rampant violence, inadequate staffing, and returning participants to prison for minor rule violations.[70]

3. Problem-Solving Courts and Treatment Programs

There is a rich literature on the operation and efficacy of problem-solving courts and related specialized diversion programs.[71] These courts and treatment programs aim to address a wide range of issues (mental health, drug treatment, human trafficking, and prostitution, among others) and have different titles, such as community courts, drug courts, and specialty courts. Nonetheless, these programs share common characteristics. Most people are referred to problem-solving courts as part of the case disposition or are required to plead guilty as a prerequisite for entering the program. Treatment programs are likewise ordered as part of a case disposition, usually in addition to some form of court supervision. Problem-solving courts and treatment programs often involve a host of rights deprivations, from limited access to counsel to suspicionless searches and mandated treatment programs.[72] Participants who successfully complete the programs are sometimes eligible to have their case dismissed and (or) their record expunged.[73] The detailed, invasive, and onerous conditions of these programs make them easy to fail. People are often reincarcerated not for new offenses, but for violations of technical requirements.[74] As a result, these programs have been criticized as net-widening, pathologizing, and ineffective.[75]

4. Electronic Monitoring and Other Forms of Technological Surveillance

Every state uses some form of electronic ankle monitoring or surveillance, which is most often imposed in addition to probation, parole, or pretrial release.[76] The use of this technology is increasing exponentially, fueled in part by the COVID-19 pandemic.[77] Although electronic monitoring data is limited, numbers from a few jurisdictions reflect its increasing use. For example, in Harris County, Texas, electronic ankle monitoring skyrocketed from a daily average of twenty-seven people on monitors in 2019 to over four thousand people on monitors in 2021.[78] In Cook County, Illinois, there were over three thousand people on monitors in 2021, which represented almost a 25 percent increase from the year before.[79] These numbers reflect national trends.[80]

Electronic surveillance includes tracking and analyzing people’s location data, monitoring online activity, searching the contents of cell phones, and recording conversations between people.[81] In reviewing agency records governing the use of electronic ankle monitors, a few themes emerge. First, people on monitors are almost always required to remain in their homes unless they receive prior permission to leave from a supervising agent or agency, a rarely straightforward process.[82] For example, visiting the doctor, attending religious services, shopping, and taking children to school all require preapproval.[83] Second, people on monitors have their precise location data tracked, analyzed, and shared with law enforcement and courts. Most of the agency records in our research did not contain any privacy protection for the sensitive data collected through ankle monitors.[84] Third, people on ankle monitors are often subject to both the rules governing court supervision, as well as the additional (and often more restrictive and invasive) rules governing monitoring.[85]

Other forms of technological surveillance are also proliferating. For example, people are often tracked through cellphone applications[86] or are required to wear devices that detect drug or alcohol use.[87] These applications and devices allow for “perfect detection of inevitable imperfections”[88] with rules and requirements, thus raising concerns about hyper-compliance, overcriminalization, and the invasiveness of the surveillance.[89] Suspicionless searches of people’s electronic devices is also common. In a fifty-state survey of rules governing court supervision, almost a quarter of the programs allow for warrantless searches of electronic devices.[90] Finally, in some places, people on court supervision must agree to have their social media accounts monitored. For example, the rules for probation in Pima County, Arizona, state: “I understand all social media accounts (e.g., Facebook, Snapchat, Twitter, etc.) are subject to search. I will provide all passcodes, usernames, and login information necessary as directed by the IPS team.”[91] Likewise, people on parole in Vermont must “provide access to any social networking sites [they] participate in to [their] Parole Officer.”[92]

B. The Scope of Rights Violations as Punishment

The rights-stripping nature of these punishments exemplifies how punishment exemption operates: these rights deprivations would likely be unconstitutional if applied outside the context of punishment. Yet, because these rights violations are part of punishment, they escape traditional constitutional scrutiny. To be sure, some extreme features of probation and parole, such as pornography bans,[93] church attendance requirements,[94] penile plethysmography testing,[95] anti-procreation requirements,[96] and full internet bans[97] have been struck down as unreasonable or not sufficiently related to rehabilitation.[98] But these cases are the exception and not the norm. Constraints as extreme as these, as well as more “garden variety” forms of non-carceral punishments, are most often upheld. These restrictions are generally either upheld with little or no explanation or, as detailed below, upheld because the restriction “reasonably relates” to a purpose of punishment or because they are incorrectly categorized as “conditions” or collateral and, therefore, are not punishment.[99]

What follows are some of the ways that non-carceral punishments routinely deprive people of constitutional rights but are nonetheless upheld as constitutional.

1. First Amendment

There are several First Amendment concerns with non-carceral punishment. First, restrictions such as internet bans, surveillance of personal electronic devices, social media account monitoring, cellphone-use limitations, and prohibitions on communicating with certain people all chill free speech.[100] Courts routinely uphold conditions of release that limit a person’s right to protest,[101] associate with certain people,[102] and visit certain cultural clubs and social organizations.[103] For people convicted of certain sex offenses, possessing pornography is sometimes banned, and more general bans or restrictions on internet use are common.[104]

Second, some non-carceral punishments compel certain types of speech.[105] For example, courts have sentenced people convicted of environmental crimes (such as illegal disposal of hazardous waste) to become members of the Sierra Club.[106] Likewise, appellate courts have upheld court-ordered treatment programs, like programs aimed at people convicted of sex offenses or shoplifting, that require participants to make statements about their culpability.[107] Other programs require participants to take polygraph tests.[108] Still other programs require participants to undergo therapy and make statements about their past drug use, mental health, and crimes—raising not only First Amendment concerns, but also Fourth and Fifth Amendment concerns.[109]

Third, some non-carceral punishments raise Free Exercise Clause concerns. For example, courts generally uphold requirements to participate in AA programs.[110] As others have noted, AA programs are religious in nature and require participants to make statements about God.[111] Prohibitions on leaving residential programs and travel restrictions related to electronic monitoring or house arrest also implicate religious freedom because people cannot freely attend religious services or worship. For example, people on electronic ankle monitors in Milwaukee must obtain specific authorization to attend church and for no more than four hours once a week.[112] Conversely, some programs require participants to attend religious programming.[113]

Fourth, restrictions that limit whom people can spend time with raise freedom of association concerns. In my nationwide survey of court supervision rules, well over half of the programs limited or regulated whom people could spend time with and (or) be around.[114] Over a quarter of the programs prohibit participants from being around people with a criminal record, with a felony conviction, or who are on court supervision themselves.[115]

Some rules also limit social relationships based on vague characteristics.[116] For example, in Alabama, people on parole must “avoid persons or places of disreputable or harmful conduct or character.”[117] Likewise, in Kansas, people must “avoid persons and places of harmful and/or disreputable character, including establishments whose primary source of income is from the sale of alcohol.”[118]

Travel restrictions that forbid people from leaving a certain geographical area, as well as curfews and prohibitions on who is allowed into someone’s home, are very common and raise similar freedom of association concerns.[119] For example, in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, people on ankle monitors are prohibited from having more than two “visitors in [their] place of residence” per day.[120] For people subject to house arrest or electronic monitoring, attending a political rally without prior approval may be a violation of their release conditions.[121]

2. Fourth Amendment

Non-carceral punishments also violate the Fourth Amendment in ways that would be clearly unconstitutional if applied outside the context of punishment. There are several features of non-carceral punishments that raise Fourth Amendment concerns.

First, most forms of non-carceral punishment involve a substantial loss of privacy. Suspicionless searches of people and homes are common features of many non-carceral punishments, most notably probation and parole.[122] In my nationwide survey of rules governing various forms of court supervision, 65 percent of the programs provided for physical searches of people’s homes, and of those, the vast majority did not require any level of suspicion or a warrant.[123] These searches impact not just the person on supervision, but also everyone in their household, violating what Professor David Sklansky terms “privacy as refuge.”[124] There is even less privacy for people in residential programs or halfway homes. For example, the Minnesota Department of Corrections requires that halfway houses “[conduct] searches of residents, their belongings, and all areas of the facility to control contraband and locate missing or stolen property.”[125]

Second, non-carceral punishments also often involve various types of body searches, which are traditionally subject to Fourth Amendment constitutional scrutiny. Drug and alcohol testing, for example, are common features of non-carceral punishment.[126] Likewise, people subjected to different forms of non-carceral punishment are often required to wear alcohol-detecting bracelets (known as SCRAM) and submit DNA samples to law enforcement.[127] These are all Fourth Amendment searches that have been upheld as constitutional.[128]

Third, the various forms of electronic surveillance raise significant Fourth Amendment concerns. Near-constant location tracking (through GPS ankle monitors), as well as monitoring and searching private social media accounts and personal electronic devices like computers and cellphones, are all Fourth Amendment searches.[129] As I detail in prior work, electronic surveillance of people on court supervision allows prosecutors and law enforcement, with the click of a mouse, to access immense amounts of personal, otherwise private data at any time of day and without notice to the person subject to the surveillance.[130]

Electronic surveillance technology used to monitor people on court supervision continues to develop. In some places, GPS ankle monitors are also equipped with audio features that emanate loud beeping alerts and facilitate two-way conversations between people on the monitors and the agents monitoring them.[131] The audio features mean that anyone within earshot will be alerted to the monitor.[132] Although the Supreme Court has taken a hard line protecting people’s location data,[133] those same protections are not extended to people on various forms of criminal court supervision.[134] For the most part, constitutional challenges to electronic surveillance of people on court supervision have been unsuccessful.[135]

3. Fifth and Sixth Amendments

Non-carceral punishments also implicate the right to counsel and the right against self-incrimination. Despite Fifth and Sixth Amendment concerns, courts generally uphold requirements that people on supervision write apology letters, discuss their alleged crime with probation and parole officers, or make other incriminating statements.[136] Because these admissions occur outside of the normal trial process, people are rarely provided counsel. And even if they have a lawyer, the role of defense counsel in problem-solving courts is often limited such that they are not a traditional advocate for their client.[137] Likewise, significant limits on free movement and surveillance of personal electronic devices also impact people’s ability to consult with a lawyer if they have one.

4. Substantive Due Process

Certain interests are so fundamental that government action cannot infringe upon them “at all . . . unless the infringement is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling state interest.”[138] There are several ways that non-carceral punishments implicate fundamental interests protected by substantive due process.

First, restraints on movement and liberty are perhaps the most common feature of most non-carceral punishments. People on house arrest, on electronic monitoring, or in halfway houses or residential treatment centers are generally forbidden from leaving without some form of pre-approval.[139] For example, people on electronic monitors in Louisville, Kentucky, are “required to remain inside of [their] residence at all times . . . . Inside means no decks, patios, porches, taking out the trash, etc.”[140] Likewise, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, people on monitors must get authorization to go to the grocery store (for one hour once a week), the laundromat (for two hours once a week), and to vote.[141] Bans on deviating from set schedules, or even taking a different route home, are also common requirements of electronic ankle monitoring.[142]

Limitations on travel and transportation methods are also common. For example, in Alaska, Washington, Vermont, and New Hampshire, people on various forms of supervision cannot operate, and in some instances purchase, a car without approval.[143] In New York City, people may be prohibited from using or entering any Metropolitan Transportation Authority subway, train, and bus for up to three years following their release.[144]

Restrictions on where, and with whom, people can live feature prominently in most forms of non-carceral punishment.[145] For example, people on electronic monitoring in Kentucky are not permitted to live in Section 8 housing or public housing. Still other programs forbid or discourage people from living in hotels, shelters, or temporary housing.[146] In many places, people are limited to only living in homes “approved” by the supervising agent.[147] Further, people cannot live with others who have a criminal record, and in some places, people must obtain permission or provide notice to their supervising agent before someone new moves into their household.[148] These restraints all burden people’s liberty interests, as well as the right to bodily autonomy.

The aforementioned curfews and limits on travel—such as prohibitions on leaving, entering, or living in a certain home, city, county, or country—infringe on liberty interests. In my nationwide survey of court supervision rules, 80 percent include some form of travel ban that either forbids people from leaving a certain geographical area or requires permission before leaving.[149] This means people are prohibited from visiting family, friends, and care providers, like doctors, without first getting permission.

Second, restraints on personal and intimate relationships are common features of non-carceral punishments that implicate individual autonomy protected by substantive due process.[150] In some places, people cannot marry without the approval of their probation or parole officer,[151] a type of restriction that has been expressly rejected in the context of prisons.[152] Relatedly, people on probation for certain sex offenses in Maricopa County, Arizona, must “obtain prior written approval . . . before socializing, dating, or entering into a sexual relationship with any person who has children under the age of 18.”[153] And in Virginia, people on monitors are required to “inform persons with whom you have a significant relationship of your sexual offending behavior as directed by your supervising officer and/or treatment provider.”[154] These restrictions limit autonomy and simultaneously reinforce the “state’s interest in cultivating disciplined sexual citizens.”[155]

Non-carceral punishments also impact the right to parent. For example, some courts have upheld restrictions on the ability to have children.[156] These restrictions can take different forms, including permanent sterilization, forced birth control, and general prohibitions against having children.[157] As Professor Alexis Karteron documents, common features of court supervision undermine the right to parent and result in the separation of families.[158] For example, courts routinely uphold limitations on living, visiting, or socializing with your own children[159] or other children.[160] Many programs include such rules.[161] Travel restrictions, as well as inclusion and exclusion zones, also undermine the ability of families to live together. Furthermore, these rules generally fail to recognize parents “as part of a broader network of caregivers,”[162] and in doing so, further infringe on family autonomy and caregiving cohesion. By violating the right to bodily integrity, the right to parent, and the “private realm of family life which the state cannot enter,”[163] these rights restrictions appear to be the “price of pleasure.”[164]

Third, non-carceral punishments often restrict people’s ability to make decisions about their own bodies. For example, mandated drug, alcohol, and mental health treatment, including treatment referred to as “moral reconation treatment,”[165] are very common, and the failure to participate can be grounds for removal from the program and potential reincarceration.[166] Random drug and alcohol tests are also customary features of non-carceral punishment.[167] Otherwise private medical and mental health records are commonly shared with treatment providers, law enforcement, and courts.[168]

Even seemingly small indignities—such as reporting the use of over-the-counter medication to a probation officer[169]—implicate bodily autonomy. Several programs also have rules related to appearance and dress.[170] In Harris County, Texas, for example, people visiting their probation officer are prohibited from wearing “revealing” clothing or clothing in “poor taste,” including “halters, short shorts, sagging pants, pajamas, house shoes, swimsuits, low cut revealing shirts/blouses, [or] clothing with vulgar language.”[171]

Finally, restrictions on people’s ability to make decisions about their employment also raise autonomy concerns. The vast majority of non-carceral punishment programs include some sort of restriction on employment, such as requiring that people obtain permission or provide notice before changing jobs, seek approval for work schedules, and comply with limitations on work hours or the type of work they can do.[172] These restrictions, in addition to the existing challenge of finding employment with a criminal record, make it difficult to maintain financial stability and cover court-imposed fees and restitution.[173]

C. Cumulative Impact of Rights Violations

Although often heralded as “decarcerative” by progressives and conservatives alike, non-carceral punishments risk reinforcing the precise racial and economic inequities that decarceration efforts seek to address. Almost all non-carceral punishment “restricts liberty, limits privacy, disrupts family relationships, and jeopardizes financial security.”[174] As such, the erasure of rights furthers the racial and economic subordination endemic to the carceral state. In addressing the impact of electronic ankle monitoring, for example, Professor Chaz Arnett exposes the extent to which monitoring “entrench[es] a marginalized second-class citizenship.”[175] Left unchecked, the rights restrictions associated with non-carceral punishments facilitate legalized and institutionalized dehumanization,[176] or what Professor Khiara Bridges terms “informal disenfranchisement,” which refers to the “process by which a group that has been formally bestowed with a right is stripped of that very right by techniques that the Court has held to be consistent with the Constitution.”[177]

While institutional anti-Black racism has always featured prominently in the functioning of the criminal legal system, oppression along other intersecting axes, such as gender, age, disability, immigration status, gender identity, sexual orientation, and housing status, are also reinforced through rights infringement.[178] Non-carceral punishments often operate as “reformist reforms” that reinforce more visibly racialized subordination and social marginalization.[179] Thanks to the efforts of activists, community organizers, researchers, and reporters, there is now a deeper understanding of the impact of rights infringements.[180]

In many respects, the various forms of non-carceral punishment mimic, even if they do not replicate, “the violence inherent in the relationship between the state and the physically incarcerated individual.”[181] The deployment of non-carceral punishments reflects the ultimate “governing through crime.”[182] The restrictive nature of non-carceral punishment may be even harsher than prison in some circumstances. Despite the challenge of obtaining a job or housing with a criminal record, or while wearing a visible ankle monitor, people subject to non-carceral punishment are often ordered to obtain a job, seek medical care, and find housing, all while complying with a myriad of mandated treatment programs and other requirements.[183] The way that non-carceral punishment expects people to do more with less may explain why some people prefer short terms of incarceration over more lengthy non-carceral punishments.[184]

Rights infringements cause both individual and collective harm. On an individual level, losing the right to move, parent, travel, speak freely, live, socialize with loved ones, or control one’s own body and home undermines dignity and personal autonomy. The near-constant surveillance and limited privacy afforded to those subject to non-carceral punishment trigger related social and emotional harms.[185] As one teenager on an electric monitor explained, she could not hide the ankle monitor, and the gaze of her teachers and classmates got to her: “You’re trying to move on with your life, but you have this black box around your ankle.”[186]

Privacy scholars have long warned that government surveillance, as well as surveillance by private companies, chills civic engagement and civil liberties and strips people of personal agency, autonomy, and voice.[187] The lack of privacy associated with non-carceral punishment also reinforces the myriad ways that informational and intimate privacy primarily belongs to people not subject to non-carceral punishments.[188]

The collective harm is also significant. The erasure of rights impacts not just the person subject to carceral control but also families and communities.[189] For example, conditions that restrict parent-child relationships or ban contact with people with criminal records break families apart and “effectively cut a supervisee off from large swaths of his entire community.”[190] Relatedly, for people subject to non-carceral punishment, the “home is opened up as never before”[191] and exposes entire families and homes—the paradigmatic private place—to carceral surveillance.[192]

D. Structural Features that Facilitate Punishment Exemption

Punishment exemption has flourished in part because of courts’ historically deferential approach to evaluating rights restrictions.[193] The failure of courts to engage—much less address—punishment exemption also stems from several structural features of non-carceral punishment, features that have the effect of shielding punishment from judicial scrutiny. As a result, courts have been able to avoid resolving the constitutionality of punishment exemption.

1. Barriers to Legal Challenges

Efforts to limit litigation have made legal challenges to non-carceral punishment virtually impossible.[194] Many rights-stripping punishments exist—and expand—because people subject to non-carceral punishments, like people in prison, are deprived of the resources necessary to bring effective legal challenges.[195] Factors such as the lack of access to counsel, the difficulty of obtaining evidence, the challenges of pro se litigation, the inaccessibility of civil trial courts, and qualified immunity make constitutional challenges difficult.[196]

There are also few opportunities to meaningfully object to the rights-restricting features of non-carceral punishment. Because non-carceral punishment is often presented as an alternative to incarceration, there is no obvious opportunity to challenge the sanction, and the accused person’s bargaining power is weak.[197] In the context of supervised release, people convicted of crimes “will accept nearly any arrangement as long as it provides them the opportunity to avoid going to prison.”[198] When the contours of non-carceral punishment are determined by third parties, there is virtually no way to challenge the rights restrictions short of a lawsuit.[199] These barriers to legal challenges essentially immunize the rights-stripping nature of punishment from meaningful scrutiny. Put differently, punishment exemption has flourished in part because challenges to it are few and far between.

2. Delegation to Third Parties

The delegation of non-carceral punishment to third-party entities, be they private companies, nonprofits, or government agencies, also explains the lack of regulatory and constitutional protections.[200] Although courts set probation conditions, it is more often parole boards, treatment centers, specialty courts, government agents, and private companies that determine the precise contours of non-carceral punishment.[201] These entities, not courts, are responsible for rule-making, enforcement, and sanctions.

The largely unregulated and nontransparent role of private industry complicates the deference afforded to the third-party entities tasked with administering non-carceral punishment.[202] For example, in some states, probation services are outsourced to private companies—often the same companies that own and operate private prisons and electronic ankle monitoring.[203] While government entities are subject to at least some forms of judicial and regulatory oversight, albeit minimal, the same cannot be said for privately run non-carceral programs. These programs are rarely transparent about their operation, nor are they required to be as they are not governed by public records laws.[204] With limited involvement of state actors, courts’ ability to monitor non-carceral programs is further curtailed.

The interests and motivations of non-court institutions that oversee non-carceral punishments—such as agencies, nonprofits, and private companies—are also not the same as those of criminal courts.[205] As Professor Eisha Jain has noted, “the organizational logic that motivates key institutions is distinct from— and often in tension with—the sentencing interests of the state.”[206] Just like the concern that private prisons prioritize profits over people,[207] there is a similar concern that private companies that market, sell, and operate various forms of non-carceral punishments are motivated primarily by financial gain.

Delegation is especially troubling in “authoritarian institutions” where “serious abuses of power and violations of rights are likely to occur” and the political process is unlikely to provide any meaningful protections.[208] As Justice Brennan warned in a dissent pertaining to restrictions on religion in prison, “we should be especially wary of expansive delegations of power to those who wield it on the margins of society. Prisons are too often shielded from public view; there is no need to make them virtually invisible.”[209] The concern about expansive delegation applies to carceral institutions that exist outside of prison as well. Like barriers to legal challenges, this delegation has the net effect of judicial avoidance: courts need not resolve, much less address, punishment exemption if the issue is not before them.

3. Lack of Regulatory Protections

The operation and management of both carceral and non-carceral punishments are often beyond the reach of not just court oversight but other regulatory regimes and agencies that oversee certain industries, like OSHA or the FDA. In the prison setting, services related to food, medical care, and telecommunications, for example, often evade the regulatory oversight that would otherwise apply outside of prison.[210] The same concerns extend to non-carceral punishments, where halfway houses, electronic monitors, and mandated treatment programs are also under- or unregulated.[211] This is not an accident. As is true with prisons, the failure of all branches of government to regulate carceral institutions—both prisons and punishment outside of prison—reflects a “palpable hostility and contempt” towards people subjected to carceral control.[212] As a result, people subject to carceral control—be it in prison or not— are left in a “deregulatory state of exception.”[213]

The private “alternatives to incarceration” industry is especially under-regulated. There are no regulations, for example, governing the production and operation of electronic ankle monitors or SCRAM devices, despite the fact that people wear these devices 24/7 on their bodies and that the devices sometimes cause physical injuries.[214] Likewise, as journalists have pointed out, state and federal regulators routinely ignore halfway houses and rehabilitation centers to the detriment of people in the programs.[215] The exorbitant fees for various “alternatives,” combined with the profit motives of private corrections entrepreneurs, also raise concerns about potential violations of federal antitrust and antimonopoly laws.[216]

In short, there is no meaningful accountability when the operation of non-carceral punishment is fully delegated to private companies or third parties. When the state incarcerates someone in prison, the state is in theory responsible for the wellbeing, health, and safety of that person.[217] The same cannot be said of non-carceral punishments, where the wellbeing of participants rests entirely with third parties and private companies. The lack of regulatory protection, and the distance between courts and the operation of these punishments, also helps explain why punishment exemption has escaped judicial review.

II. The Case Against Punishment Exemption

Having established the rights-restricting nature of non-carceral punishment, this Section makes the case that there is no doctrinal basis to exempt rights-restricting punishments from traditional constitutional review that would otherwise apply outside of the punishment context. The case against punishment exemption is most vivid in the context of non-carceral punishment, but many of the reasons to reject punishment exemption apply to prison sentences as well.

As a threshold matter, the absence of clear doctrinal support for punishment exemption stems, at least in part, from a profound disagreement about the legal origins of liberty. In a doctrinal tug-of-war, Justices Stevens, Brennan, and Marshall generally viewed liberty as an unalienable right that is not easily extinguishable. Just as an incarcerated person “[does] not shed all constitutional rights at the prison gate,”[218] neither does a person subject to non-carceral punishment upon starting their punishment. In contrast, Justices White, Rehnquist, and Thomas viewed liberty as being rightly extinguished by incarceration, and to the extent that liberty interests remain, they are derived from federal or state law creating entitlement.[219] This approach is consistent with the concept of departmentalism, in which ultimate authority in constitutional interpretation resides with “the people themselves.”[220]

This debate helps explain why no court has offered a sound explanation or justification for punishment exemption. Instead, most courts examining non-carceral punishments either assume that no constitutional scrutiny applies or apply the reasonably related standard—but neither approach explains why traditional constitutional scrutiny does not apply. Although Justices Thomas and Scalia stated in a dissent that the Court has consistently refused to apply strict scrutiny to prison sentences,[221] and some state court judges have likewise explicitly refused to apply strict scrutiny to the deprivation of rights associated with punishment,[222] there is no solid doctrinal explanation, much less justification, for this position. This Section exposes these doctrinal infirmities.

A. No General “Punishment Exception” to the Constitution

This Article’s central claim is that a criminal conviction does not give the state license to impose rights deprivations as punishment so long as such deprivations are not cruel and unusual. As Justice Stevens warned in his dissent in Samson, there is no history of courts imposing the deprivation of Fourth Amendment rights as a “punitive measure,”[223] and as such, parole search conditions are not immune from close constitutional scrutiny.[224] This warning applies equally to all forms of punishment and is consistent with prior Supreme Court proclamations that there is “no iron curtain drawn between the Constitution and the prisons of this country.”[225] There is also no such curtain between the Constitution and non-carceral punishments.

It follows that there is no textual support for punishment to escape traditional constitutional rules that would otherwise apply. Specifically, there is no suggestion, much less a clear statement, within the Constitution that punishments are exempt from normal levels of constitutional scrutiny. In fact, the Constitution’s drafters used clear categorical language when addressing which specific rights could be infringed upon or circumscribed and why. The only two rights and privileges singled out by the Constitution’s drafters as capable of being legally abridged as punishment are the right to vote and the right to be free from slavery and involuntary servitude.[226] Section Two of the Fourteenth Amendment provides that the right to vote may be “abridged” upon “participation in rebellion, or other crime,”[227] and the Thirteenth Amendment prohibits slavery and involuntary servitude “except as a punishment for crime.”[228]

Extensive criticism notwithstanding, exploitative prison labor and felony disenfranchisement have been upheld as legally permissible forms of punishment.[229] To be sure, these provisions are rightly questioned and challenged,[230] and I agree with scholars and policy-makers calling for their abolition.[231] Yet under basic canons of construction, these two provisions undermine the idea that there is an implicit or general punishment exception to the Constitution.[232] The failure of the drafters to use limiting language elsewhere suggests that a conviction cannot be the sole grounds to deny people rights.

Some might argue that if the text of the Thirteenth Amendment in fact allows involuntary servitude and slavery as punishment, it follows that any rights deprivation as punishment is permitted under the Constitution, since “lesser” punishments are less rights depriving than enslavement. Yet even accepting the textual support for such a position—a reading that scholars debate[233]—current punishment jurisprudence rejects slavery and “civil deaths” as punishment for a crime, addressed infra in Part II.B.

To be sure, the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments are arguably distinguishable from other constitutional provisions because they were part of the Reconstruction compromise. As addressed more thoroughly by other scholars, the Thirteenth Amendment both ended the formal institution of slavery but also ensured the entrenchment of race- and class-based hierarchies with “Black codes,” convict leasing, and other mechanisms that perpetuated slavery through the Punishment Clause.[234] Yet, if we take at face value the general view of courts that the Punishment Clause “strips convicted persons of Thirteenth Amendment protection,”[235] it follows that there is no other general punishment exception beyond the Punishment Clause.

Moreover, the elimination of rights for people subject to carceral control reflects the “badges and incidents of slavery”[236] that the Thirteenth Amendment forbids.[237] As discussed in greater detail in Part IV, the concerns that led to the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments directly undermine exempting punishment from traditional constitutional protections. In particular, the brutal practices of separating enslaved families and the inhuman treatment of enslaved people motivated the passage of the Reconstruction Amendments.[238] Yet today, as Professor Brandon Hasbrouck explains, liberty restrictions related to punishment strip people of “fundamental privileges and immunities of citizenship, including restrictions on speech, family relations, and legal status—all of which are textbook examples of badges and incidents of slavery.”[239] For all these reasons, the Reconstruction Amendments—and in particular the Thirteenth Amendment—undermine the proposition that punishments are categorically exempt from traditional constitutional scrutiny.

B. The “Right to Have Rights”

On multiple occasions, the Supreme Court has made clear that the protections of the Free Exercise Clause, the Due Process Clause, and the Equal Protection Clause all apply to people subjected to various forms of non-carceral punishment,[240] and that people in the criminal legal system do not “forfeit all constitutional protections.”[241] Despite this strong categorical language, punishment exemption persists.

There is no obvious doctrinal support for the argument that punishment or a conviction alone fully extinguishes the right to have rights.[242] As the Ninth Circuit noted, being on probation does not “extinguish” Fourth Amendment rights, and a “conditional releasee may lay claim to constitutional relief, just like any other citizen.”[243] There is nothing special about state action in the form of punishment that exempts it from scrutiny. The rules of constitutional law should be the same across contexts: the relevant constitutional scrutiny should apply to all state action, regardless of whether the state action is categorized as punishment, regulation, or a collateral consequence.[244] Focusing on non-carceral punishments in particular highlights why rights-violating punishment, and exempting punishment from traditional constitutional review, is not legally justified.

There are several reasons to subject non-carceral punishment to traditional levels of constitutional scrutiny. First, simply erasing rights as punishment is a form of “civil death,” defined as a “form of punishment” that “extinguish[es] most civil rights of a person convicted of a crime and largely put[s] that person outside the law’s protection.”[245] While civil death was a common colonial-era punishment, it is no longer accepted. In 1997, the Supreme Court held that “the ancient common law doctrine of ‘outlawry,’ and . . . ‘civil death,’ . . . could not be admitted without violating the rudimentary conceptions of the fundamental rights of the citizen.”[246] Likewise, in 1977, Justice Marshall explained in a dissent that the Court has repeatedly rejected the view once held by state courts that “prisoners were regarded as ‘slave(s) of the State,’ having not only forfeited [their] liberty, but all [their] personal rights . . . .”[247] As Justice Stevens explained in a separate case:

[I]f the inmate’s protected liberty interests are no greater than the State chooses to allow, he is really little more than the slave described in the 19th century cases. I think it clear that even the inmate retains an unalienable interest in liberty at the very minimum the right to be treated with dignity which the Constitution may never ignore.[248]

This concern is not limited to prisons and applies equally to non-carceral punishments as well.

Restrictions on Second Amendment rights have garnered similar concerns about targeting and eliminating rights for people with criminal convictions.[249] For example, before joining the Supreme Court, then-Seventh Circuit Judge Amy Coney Barrett observed in a dissent that “[f]ounding-era legislatures did not strip felons of the right to bear arms simply because of their status as felons.”[250] As she explained, history teaches us that “a felony conviction and the loss of all rights did not necessarily go hand-in-hand.”[251] While most Second Amendment restrictions are categorized as collateral consequences or civil restraints, Justice Barrett’s position suggests deep skepticism of any firearms restriction (punitive or collateral) that is triggered solely by someone’s status as a “felon.”[252] Of course, there is nothing exceptional about the right to bear arms as compared to other fundamental rights. In theory, Justice Barrett’s concern extends to all rights and undermines the legitimacy of punishment exemption generally. At the very least, it suggests a conflict between the protection afforded to Second Amendment rights as compared to other rights.

Second, as a doctrinal matter, the loss of rights in prison, or in non-carceral settings, is most often justified because maintaining the rights would be inconsistent with the operation of the punishment. But the rights are not taken away as the punishment itself. As Professor Sherry Colb explains in the context of prisons, “we do not sufficiently scrutinize the penalty of incarceration as a deprivation of the fundamental right to be free from physical confinement.”[253] The same can be said of non-carceral punishment. Indeed, scholars have rightly called for heightened constitutional scrutiny of both punishments and collateral consequences, regardless of their label as punishment or not.[254] There is nothing exceptional about criminal punishments that justifies unique constitutional treatment.[255]

Third, Supreme Court punishment and prison jurisprudence offers no clear categorical rule that exempts rights-violating punishments from traditional constitutional review. Instead, the case law reflects ongoing tension about what scrutiny is due.[256] On one hand, the Court appears to have rejected the applicability of strict scrutiny to punishment. In Chapman v. United States, the Court entertained a substantive due process challenge to a mandatory five-year sentence that was based on the weight of the container of drugs plus the drugs, as compared to the weight of the drugs without the container.[257] The Court rejected the challenge and upheld the sentence under rational basis review.[258] Notably, the Court did not explain why it applied rational basis review and not strict scrutiny. In one short paragraph, the Court simply explained that once a person is convicted of a crime, courts may impose whatever punishment is authorized by statute so long as it is not cruel and unusual and not irrational under rational basis review.[259]

On the other hand, Chapman’s legacy is as uncertain as it is unclear. In the years after Chapman, the Court expressed concern that any institutionalization of an adult “triggers heightened, substantive due process scrutiny”[260] and requires a “‘sufficiently compelling’ government interest.”[261] To be sure, these concerns appear in the context of civil commitment, not criminal incarceration. For example, in striking down the ongoing civil commitment of an insanity acquittee, the majority in Foucha v. Louisiana distinguished civil commitment from criminal incarceration.[262] Because the commitment was civil and not criminal, the majority reasoned, substantive due process protections applied.

Yet the difference in settings does not, without more, explain why punishment should be treated differently for purposes of substantive due process analysis.[263] Indeed, in his dissent in Foucha, Justice Thomas worried that the majority’s focus on criminal convictions was just a question of semantics. As he explained, “I am not sure that [a conviction] deserves talismanic significance” because “[i]t is surely rather odd to have rules of federal constitutional law turn entirely upon the label chosen by a State.”[264] In short, the civil-criminal distinction is of limited use since substantive due process “protects bodily liberty, full stop, and one’s bodily liberty is equally constrained regardless of whether the judicial order doing the work is styled as a civil or a criminal judgment.”[265]

In the equal protection context, the Supreme Court has also applied strict scrutiny to prisons, suggesting that Chapman is not the final word on the legality of exempting punishment from traditional standards of constitutional review. In evaluating a Section 1983 equal protection challenge to prison policies that discriminated based on race, the Court explicitly held that strict scrutiny and not the reasonably related standard governed the challenge.[266]

To be sure, there is debate in the law and literature about what precise constitutional review is due,[267] but at a minimum, these cases all reveal that criminal punishment—both in prison and out—is not per se exempt from constitutional scrutiny and that there is no obvious reason not to apply traditional constitutional scrutiny to punishments.[268]

Reading the cases this way is not novel. Justices Marshall and Brennan also believed that the traditional levels of constitutional scrutiny that apply to any state action should apply to state action in prison. In a dissent related to a freedom of association claim, Justice Marshall urged the Court to view restrictions on First Amendment activities the same for people in prison and outside.[269] In a dissent regarding restrictions of religious practices in prison, Justice Brennan likewise took the position that such restrictions should be subject to a “strict standard of review.”[270]

These points, however, raise a follow-up question: if traditional constitutional scrutiny applies to non-carceral punishment, why have courts avoided doing just that? In 2001, the Wisconsin Supreme Court offered a possible explanation. In upholding an anti-procreation probation condition, the court in State v. Oakley noted, without citation to authority, that neither probation conditions nor prison regulations are subject to strict scrutiny review.[271] The court explained its reasoning:

If probation conditions were subject to strict scrutiny, it would necessarily follow that the more severe punitive sanction of incarceration, which deprives an individual of the right to be free from physical restraint and infringes upon various other fundamental rights, likewise would be subjected to strict scrutiny analysis. . . . [This] position is either illogical in that it requires strict scrutiny for conditions of probation that infringe upon fundamental rights but not for the more restrictive alternative of incarceration, or it is unworkable in that it demands the State meet the heavy burden of strict scrutiny whenever it is confronted with someone who has violated the law.[272]

Yet this explanation is suspect. It is hardly illogical to suggest that strict scrutiny applies to both carceral and non-carceral sentences. Both, after all, involve state action and the deprivation of liberty, just to different degrees. Likewise, the unworkable explanation seems to suggest, as Justice Brennan famously put it, a “too much justice” problem.[273] Simply because applying traditional constitutional scrutiny would be difficult is not, without more, a sufficient justification to not do so. Perhaps the real reason courts avoid applying traditional constitutional scrutiny to punishment is that it opens the floodgates to constitutional challenges and might result in substantially limiting the State’s ability to punish people with both carceral and non-carceral sanctions. In this way, courts’ reliance on the consent of people convicted of crimes, as well as deference to agencies and private companies, should be viewed as forms of judicial avoidance.

To be sure, a small handful of courts reject the idea of punishment exemption and have instead applied heightened levels of constitutional scrutiny to non-carceral punishments. For example, then-Second Circuit Judge Sonia Sotomayor invalidated a supervised release condition that limited a parent’s ability to visit with his child on the grounds that “the liberty interest at stake is fundamental” and “a deprivation of that liberty is ‘reasonably necessary’ only if the deprivation is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling government interest.”[274] A handful of courts followed suit in the context of family relationships, but they are the exception and not the norm.[275]

Notably, most of the cases that apply strict or heightened scrutiny to non-carceral punishments involve more extreme rights restrictions, such as prohibitions on having children, complete internet bans, or mandatory penile plethysmographs.[276] Another small group of judges have subjected religious restrictions and speech restrictions to heightened scrutiny.[277] But these cases are outliers and inexplicably apply heightened scrutiny to some restrictions and strict scrutiny to others.[278] Nonetheless, these cases—many of them state court decisions—suggest that rights restrictions imposed as punishment are not categorically exempt from close constitutional scrutiny.

The vast majority of courts confronted with challenges to non-carceral punishments, however, either avoid the constitutional questions altogether, uphold restrictions that “reasonably relate” to a purpose of punishment (a form of rational basis review), or explicitly refuse to apply traditional constitutional scrutiny.

C. Prohibition on Punishments that Ruin People and Undermine Dignity

Rights-violating punishments also conflict with both Eighth Amendment and substantive due process jurisprudence that speaks to dignity interests and personal ruin. While scholars have understandably questioned the continued viability of both substantive due process and Eighth Amendment challenges to various forms of punishment, a close reading of recent case law reveals reason to think otherwise.

In the context of the Eighth Amendment, two recent cases suggest a prohibition on punishments that ruin people. The Supreme Court’s decisions in both United States v. Bajakajain and Timbs v. Indiana reflect a recognition that punishment is not meant to leave a person in a worse condition by depriving them of basic rights, liberty, and autonomy.[279] Although both cases focus on the scope of the Eighth Amendment, the decisions aimed to limit “punishment powers to exploit and undermine individuals . . . , to ‘retaliate or chill’ speech, or otherwise to abuse people.”[280] As Professor Judith Resnik explains, Timbs suggests an “anti-ruination principle,” which is the idea that “state punishment has to preserve (rather than diminish) people’s capacities to function physically, mentally, and socially, even as governments may also aim to deter, incapacitate, be retributivist, rehabilitative, protect institutional safety, and minimize costs.”[281]

The anti-ruination principle can be traced back further than Timbs and beyond the Eighth Amendment. In rejecting the view that the Eighth Amendment is the only limit on punishment, Justice Stevens explained that “it remains true that the ‘restraints and the punishment which a criminal conviction entails do not place the citizen beyond the ethical tradition that accords respect to the dignity and intrinsic worth of every individual.’”[282]

The rights deprivation associated with non-carceral punishment does precisely what Professor Resnik warns against: it diminishes a person’s ability to function physically, mentally, and socially. Instead, as suggested by Justice Stevens, punishment should preserve certain aspects of a person’s liberty and dignity. Depriving people in prison of pictures of their loved ones, for example, “may mark the difference between slavery and humanity” and does not “comport with any civilized standard of decency.”[283] Likewise, in the context of the decades-long California prison condition cases, Judge Thelton Henderson explained that when prisons deprive people “of a basic necessity of human existence[,] . . . they have crossed into the realm of psychological torture.”[284] The same analysis can and should apply in the context of non-carceral punishments.

Both the Eighth Amendment and substantive due process also speak to dignity interests—interests undermined by many of the rights-restricting non-carceral punishments. In many of the early reproductive health care cases, for example, the Supreme Court spoke about the Fourteenth Amendment’s liberty guarantee as respecting personal autonomy as well as dignity.[285] Dignity interests—as part of substantive due process—appear in a range of cases, including the right to refuse life-sustaining medical care and the right to privacy with respect to sex and sexuality.[286] To be sure, post-Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the ongoing viability of these cases is unknown, an issue addressed infra in Part IV.

The concern with dignity is not limited to the Fourteenth Amendment. Eighth Amendment jurisprudence also invokes dignity as an organizing principle by which to evaluate punishment.[287] As Justice Brennan famously noted, “punishment must not be so severe as to be degrading to the dignity of human beings.”[288] In concluding that handcuffing someone to a hitching post for seven hours and not letting them use the bathroom violated the Eighth Amendment, the Court explained that the punishment was “antithetical to human dignity” and emphasized that the “basic concept underlying the Eighth Amendment . . . is nothing less than the dignity of man.”[289] In that case, the Court found that the prison’s inability to meet basic human needs is a feature of punishment that undermines dignity and thus violates the Eighth Amendment.[290] As explored more fully in related work, punishments that may not amount to torture and could be justified as reasonably related to rehabilitation or deterrence—for example, requirements to urinate in front of a state official as part of a drug test or limits on parenting—could still raise significant dignity concerns.[291]

A historical reading of the Eighth Amendment also supports the proposition that the right against cruel and unusual punishment means more than the right to not be tortured. Under the original meaning of “unusual,” punishments were presumed unjust if they “attempted to replace ‘reasonable’ punishment practices that had developed over a very long period of time with something that was either new, foreign, or previously tried and then rejected.”[292] Arguably, some forms of non-carceral punishments are sufficiently “unusual” so as to justify Eighth Amendment protection.

D. Reasons to Reject the Reasonably Related Standard

Punishment exemption is very much fueled by courts’ deferential approach to reviewing rights-restricting punishment.[293] Generally, courts either ignore the rights-stripping nature of punishments or uphold rights restrictions that reasonably relate to rehabilitation or public safety.[294] For example, restrictions that implicate First Amendment rights (such as mandatory participation in AA or restrictions on movement that implicate the ability to protest or practice religion) or restrictions on family and social relationships are routinely upheld under a reasonably related justification.[295] A condition requiring a person on probation to seek permission from his probation officer before “engaging in sexual relationship[s]” was also upheld as reasonably related to rehabilitation.[296] Likewise, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, a federal district court judge ordered that a probationer receive a COVID-19 vaccine on the grounds that it reasonably related to public safety.[297]

This Section takes on the reasonably related standard and makes the case that it does not justify exempting non-carceral punishment from traditional constitutional scrutiny.

1. Limitless Limit

The reasonably related standard is not random. It migrated from prison jurisprudence to non-carceral jurisprudence with little adaptation for the differences between carceral and non-carceral settings. In the prison context, most rights restrictions are upheld so long as the burdens are “reasonably related to legitimate penological interests,”[298] including rehabilitation and public safety.[299]